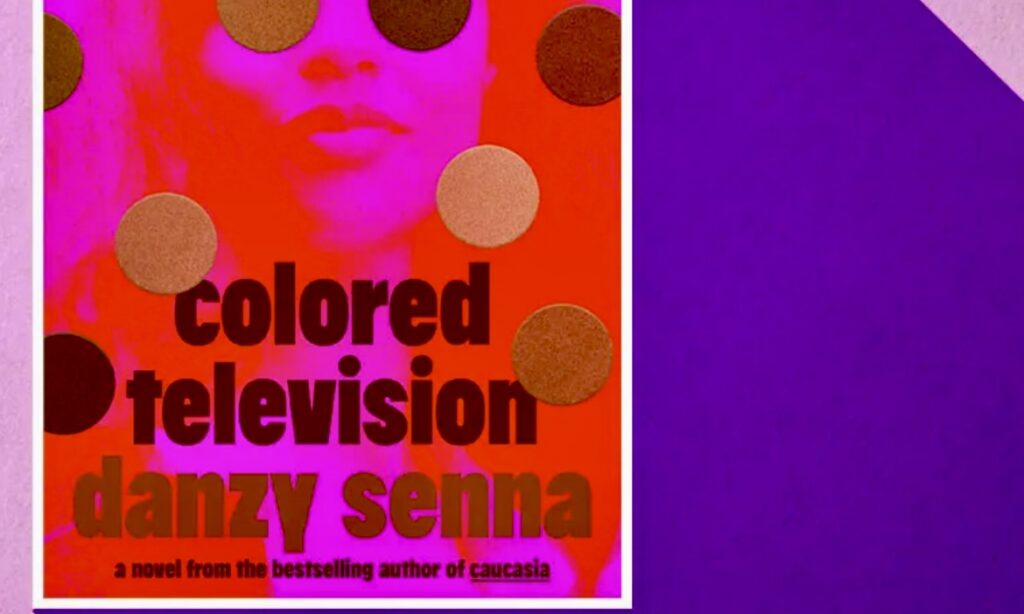

It’s a rare novel that is satirical and compassionate, laugh-out-loud funny and bracingly provocative, easy to read and layered with trenchant observations about race. This one, Danzy Senna’s latest, Colored Television, centers the experience of being an American “mulatto” (both the author and characters’ preferred term, a pointed reclaiming of problematic language) while lacerating the pretensions of Hollywood. Protagonist Jane, product of a failed interracial marriage, has written her “mulatto War and Peace,” a chaotic saga that has taken nine years to finish and bewilders her agent and editor, who advise that she “expand her territory” and not do herself “a disfavor by writing about…the whole mixed-race thing.” Jane’s uncompromising Black artist husband Lenny finds nobility in her failure, but now that they have two young children, Jane is sick and tired of being members of the cultured creative class without money or privilege. Their family, unable to actually afford living in LA, moves from this rich friend’s converted garage to that rich friend’s architecturally-pedigreed house with increasingly depressing rentals in between.

The events of the book unfold in Jane’s graduate-school-friend Brett’s aforementioned house in the hills, paid for by his successful “sell-out” work in television. Jane’s aspirational materialism is fueled by close proximity to wealth’s trappings and the rejection of her epic “history for a people without a race.” Stoked by covetousness, frustration with her faltering marriage, and susceptibility to bourgeois catalogue imagery, Jane finagles a meeting with Brett’s agent and ends up pitching a TV series about mulattos to another “mixed nuts” character, the powerful producer, Hampton Ford.

As Jane—secretly, hopefully, guiltily—brainstorms ridiculous sitcom episodes (a pet Labradoodle neuters a “threatening” Black man, a DNA testing kit precipitates stereotypical behaviors), she embraces this intoxicating new life. She and Hampton swap stories—hers, notably, about a life-changing realization in a Restoration Hardware showroom; his, notably, about a Kardashian birthday party—and she dares to imagine possible future rewards. As her difficult father has told her, “race was always about money, and money was always about race.” Even as Lenny self-righteously resists representing the “Black experience” in his paintings (rendering them unsaleable), Jane is eager to abandon the superiority of high art to monetize her identity. And what influences the culture more than television?

Senna’s ability to write honestly and unflinchingly about race is only one reason to read Colored Television. She is also hilarious about teaching, marriage, culture, and parenting. As Jane matures—a process made necessary by her failures, her family, her facing reality—she makes a kind of peace with her singular, asymmetrical, mulatto self. I hope and expect that Senna will continue to do herself and us the favor of continuing to write about “the whole mixed-race thing.”