I’ve always loved historical fiction–the idea of connecting deeply with people who lived so long ago, their lives carefully and lovingly restored by the writer, feels as close to magic as one can get. This precious time travel helps me forget about the current state of affairs (which, at the moment, feel especially precarious), and for a little while, I can walk with ancient Queens or watch William Shakespeare pen Hamlet or carry laundry from the river with pioneer women. But it takes a very talented writer to make all those elements come together in a historical fiction novel, and Maggie O’Farrell is one of the best I’ve ever encountered.

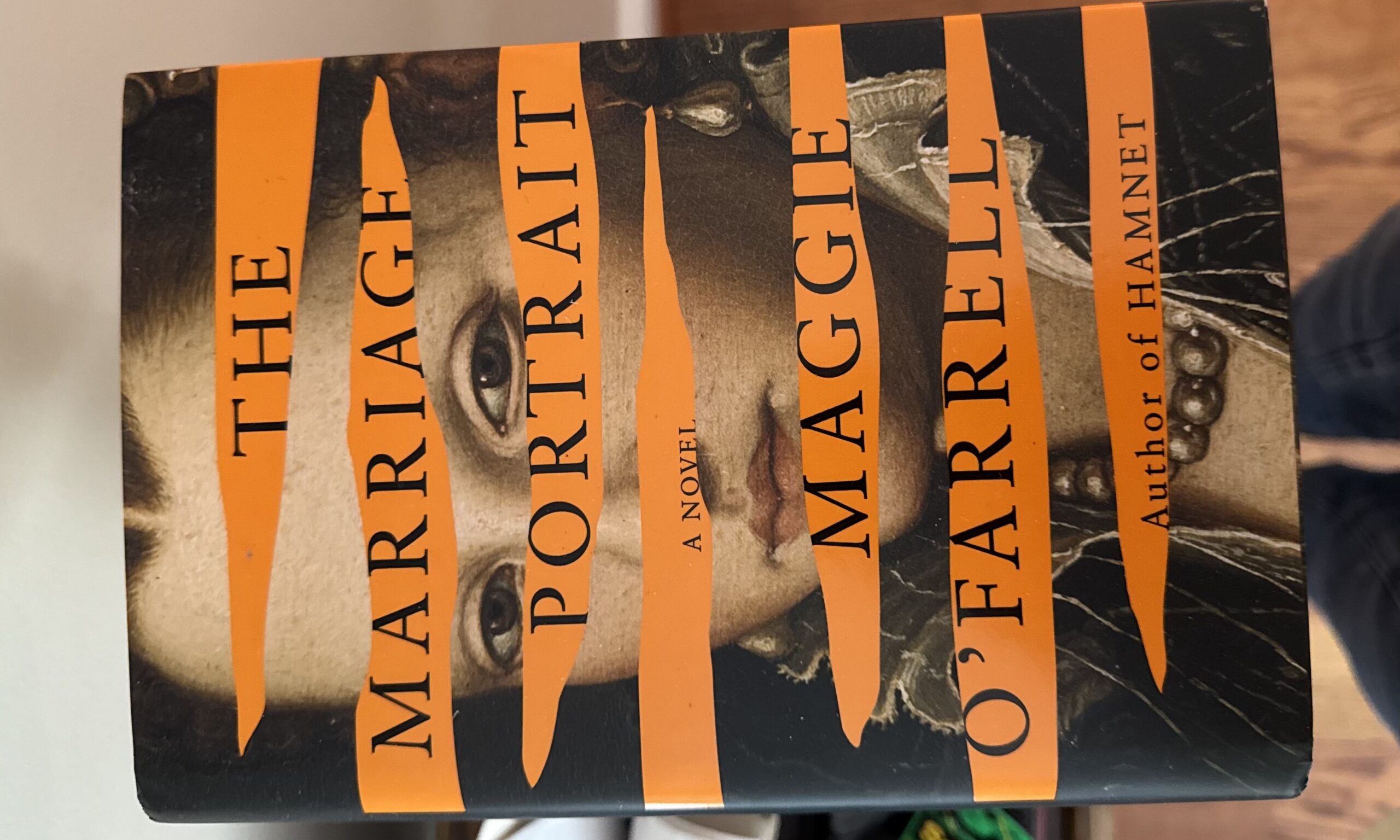

O’Farrell finds her story for The Marriage Portrait within a poem by Robert Browning called “My Last Duchess.” In it, a duke demonstrates a clear obsession with controlling his duchess’ every move. The poem is possibly based on a real person, Lucrezia de Medici, who may have been murdered by her husband, the Duke of Ferrara. O’Farrell takes that dark poem and releases Lucrezia from her poetical prison by imagining a wild, enchanting life–and a new ending–for the fiery de Medici girl. In The Marriage Portrait, fact marries fiction in the most delicate way, and by choosing a rather obscure historical figure, O’Farrell is able to reimagine a full life for her heroine.

As the facts go, Lucrezia de Medici was married to the Duke of Ferrara at around 13, after her older sister, his originally intended bride, died suddenly. A short time later, at just 16, Lucrezia also died suddenly, her death long believed to have been caused by poisoning at the hand of her husband.

O’Farrell’s version follows the young de Medici girl as she grapples with and prepares for her marriage to the shadowy Duke of Ferrara, allowing readers to hear her inner thoughts. Bouncing between temporalities (at the start, Lucrezia is newly married and convinced her husband is going to kill her that night while the next chapter rewinds to her conception and childhood), O’Farrell paints a picture of life in the Florentine court. And through this narrative navigation, Lucrezia becomes a living, breathing teenager.

As always, O’Farrell sticks closely to historical fact, but tweaks a few details here and there to help the plot move along more fluidly. (This artistry was equally on display in her incredible book Hamnet, which imagined William Shakespeare’s experience with his son, who died young, and also reimagines another shadowed historical figure: his wife Anne.) She makes Lucrezia just a little older in her book, and more artistically minded—Lucrezia is a talented painter. O’Farrell also weaves in a romantic interest that creates a bright spot for poor Lucrezia outside of her likely loveless marriage.

O’Farrell’s historical accuracy and attention to detail are top-notch, but her beautiful writing is even better. Her scenes are rich, full of color and life, while her dialogue is moving and meaningful. The result is a novel that feels more like an HBO show than a bookstore impulse purchase.

We think we know how this one will end, but O’Farrell has a surprise in store. By softening the doom-and-gloom historical ledger, she leaves the door (or in this case, window) open for Lucrezia to tell her own story. This is what I love most about O’Farrell’s book: She gives this woman a second life—one that looks a little better, and brighter, than her real one.