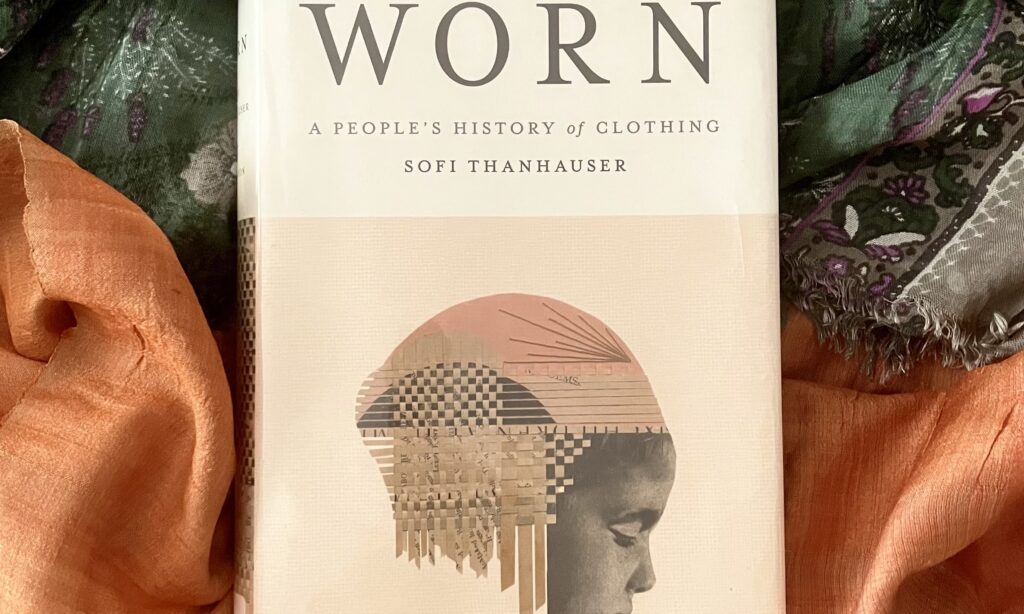

One of my favorite recent podcasts is Articles of Interest, a spinoff of the amazing design podcast 99% Invisible. Articles of Interest offers historical deep dives into clothes—sometimes a style, sometimes a specific item of dress. For a recent series about the history of preppy fashion (fascinating and completely not what you imagine), host Avery Trufelman name-checked a phenomenal, groundbreaking, and illuminating socio-historic account of fabric: Worn by Sofi Thanhauser.

This incredible read is divided into five sections, each of which traces one of the fundamental fabrics that clothe us: linen, cotton, silk, synthetics, and wool. The book is subtitled A People’s History of Clothing, but it’s much more than that—we see the biological or chemical origins of these materials, the history of their manufacture, and their human and ecological costs.

Much of this is a predictable bummer. I was already a thrift-store shopper before reading this, fully convinced that there are already more than enough used things—say, metal forks—for no one to need to buy a new one ever again. But after absorbing Thanhauser’s meticulous research on just how ruinous cotton, rayon, and nylon production is for the environment and how exploitative the industrial system of clothing manufacture is for the people—mostly women in the developing world—unlucky enough to be a part of it, I basically never want to buy anything new again.

This makes it sound as though the book is a miserable scold, but that is very far from the truth. Thanhauser’s prose is luminous and full of arresting details, and her goal isn’t to make readers feel guilty but to investigate together. Some of the best parts are descriptions of Thanhauser’s heist-like adventures trying to sneak into factories or interview workers forbidden to talk to journalists. She is not a reporter, but a professor of writing at Pratt, which shows in the immaculate characterizations of the farmers, hobbyists, and artists she encounters. Plus, the book isn’t all doom and gloom. The last section, about wool, focuses on small-scale operations trying to find a less destructive approach to fabric production.

My favorite section is the bittersweet story of forgotten hero Clara Lemlich, a Jewish immigrant to the US who fomented one of the biggest strikes of New York City’s women sweatshop workers of the early 20th century. Led by Lemlich, the newly-formed International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union demanded not just better treatment and pay, but also educational and cultural access, arguing for what amounted to a right to art. This deeply moving platform was popular enough to attract the support of middle-class women and successful enough to force labor laws to be rewritten. For a hot second, there was promise of utopia: the ILGWU opened resorts for members, created an educational department that offered courses in the liberal arts, ran healthcare centers and a radio station that alternated Vivaldi and folk music. It was short-lived of course, but Thanhauser’s breathless description makes it come poignantly alive. I left the book wondering whether we could muster so much promise, so much idealism, again.