As I review this massive and delicious novel, I confess that I adore stories that illuminate a swath of history and those where we are invited to inhabit, with the characters, a rambling (and decrepit) English country home, where it is assumed that we understand the etiquette of the era because the characters are governed by it. As a child, I gobbled up Anya, went through a Tudor obsession, was recently consumed by Maggie O’Farrell’s The Marriage Portrait, lose myself in Kate Morton novels, listen to Jennifer Robson on audio books—give me a period piece, particularly one set in England, and I am all in. Another truth: I am a drama teacher who fell in love with making plays as a child and have kept making them. And as a small claim to fame in the world of historical novels, I proudly share this tidbit: Lauren Willig, whose amazing historical novels (Band of Sisters and Two Wars and a Wedding) regularly top the NYT bestseller list, was my student! I advised her first foray into writing historical fiction when she was a senior in high school.

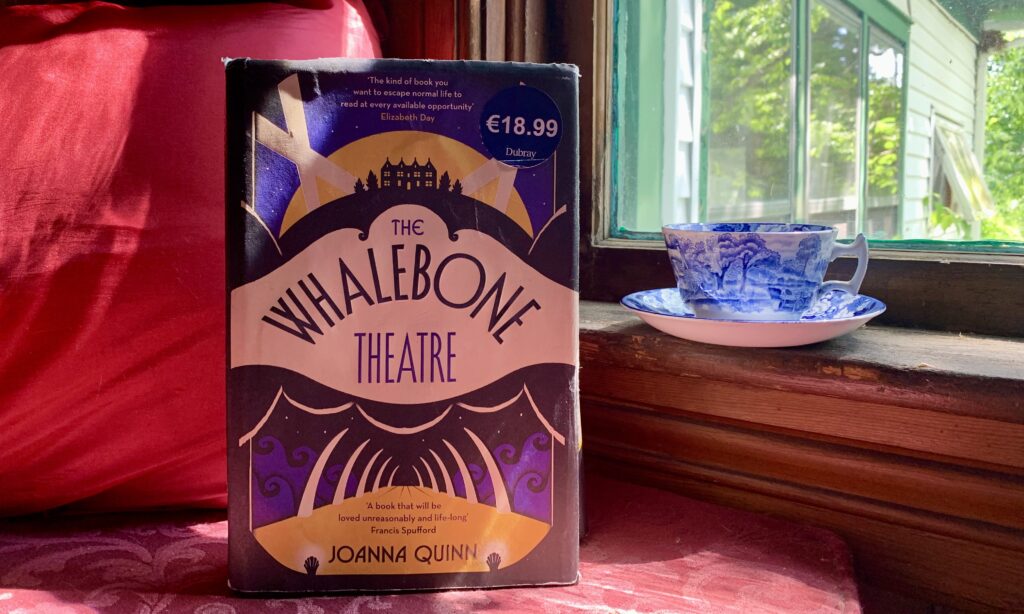

All this to say, I was, perhaps, pre-determined to love The Whalebone Theatre, a novel by Joanna Quinn that centers, certainly in its first third, on a lonely girl whose creation of Shakespearean productions within the carcass of a whale helps to shape her identity during the early decades of the 20th century. Whalebone makes me think of corsets, but, in this case, the enormous whale skeleton serves as the device for the creation of a theatre, a fantastic vision brought to life. Like other family sagas, I did not want this one to end.

Since I first read Quinn’s book a year ago, moments have stayed with me: Cristabel wandering the huge estate in which she grew up, neglected; the theatre scenes, of course, with her stepmother’s swashbuckling lover playing the leading man; her care for her much younger step-brother and step-sister, Digby and Flossie; and the later scenes set in London and France during WWII with undercover identities assumed and discarded the way actors inhabit roles and then, finished with one play, breathe life into another character. The war years are drawn with great specificity.

I love a good tale that spans decades with characters we care about. Often WWII novels start during the war, but Quinn gives us the backdrop, setting the scene by showing us the childhoods of the main characters, Cristabel, Digby and Flossie, and illustrating the ways in which loss devastates families. Cristabel, my favorite, is motherless, lonely, and in the “care” of a vacuous and nasty stepmother. Like a more modern version of Mary Lennox or Jane Eyre, she does not suffer fools gladly and names the hypocrisy she perceives, earning little affection from the adults in her world. Digby is a kindred spirit for Cristabel, a confidante and lover of language and plays, too. Flossie is a great foil, much more conventionally drawn—though she, too, evolves as a character with unexpected passions. There is family drama, lovers, death, servants who care more for the children than the parents do, and there’s the carelessness of a life between the wars juxtaposed against the crushing expenses of keeping an enormous estate going. In 1928, a whale carcass washes partially onto Chilcombe’s shores, which fires Cristabel’s imagination. She, the impresario, creates the theatre, designs the productions, establishes the tradition of doing plays. She directs Digby, his skills as an actor useful in his later work for the Resistance.

For me, Quinn is at her best when writing about plays: The Tempest staged in the whale skeleton; a production of Antigone produced in Paris in 1944—the Anouilh version which, in itself, was a form of resistance to Nazi occupation. She knows what plays feel like—the expectant hush and reverence that falls as we anticipate the play’s start, the ability to transform our world with words and actions. And, of course, her novel itself is divided into five acts, as were all good Elizabethan scripts. The story traces 26 years in the life of the family. Cristabel ends up in France as a spy searching for Digby: tragedy ensues, as it did so often during the war. To say more would threaten your enjoyment of the plot.

There are letters and lists and breaks in the narrative that reminded me of family albums stuffed with the precious detritus of a long-ago generation—telegrams, programs from plays, dance cards, photographs of people whose names are lost. These extra bits give us the sense that we are bearing witness: the personal intrudes on the authorial voice in intimate ways.

Please indulge in this story. Curl up on a window seat with a cup of tea and lose yourself in this sprawling tale of an English family from another time.