I’m a sucker for a beautiful sentence. Show me an artfully turned phrase, and I’ll follow its creator anywhere. Such is my relationship to Julie Otsuka, whose spare, dreamlike writing still haunts me months later. Although I came late to her books, I’ve since hunted down her backlist, bought each one in bulk, and gifted everyone I know with multiple copies.

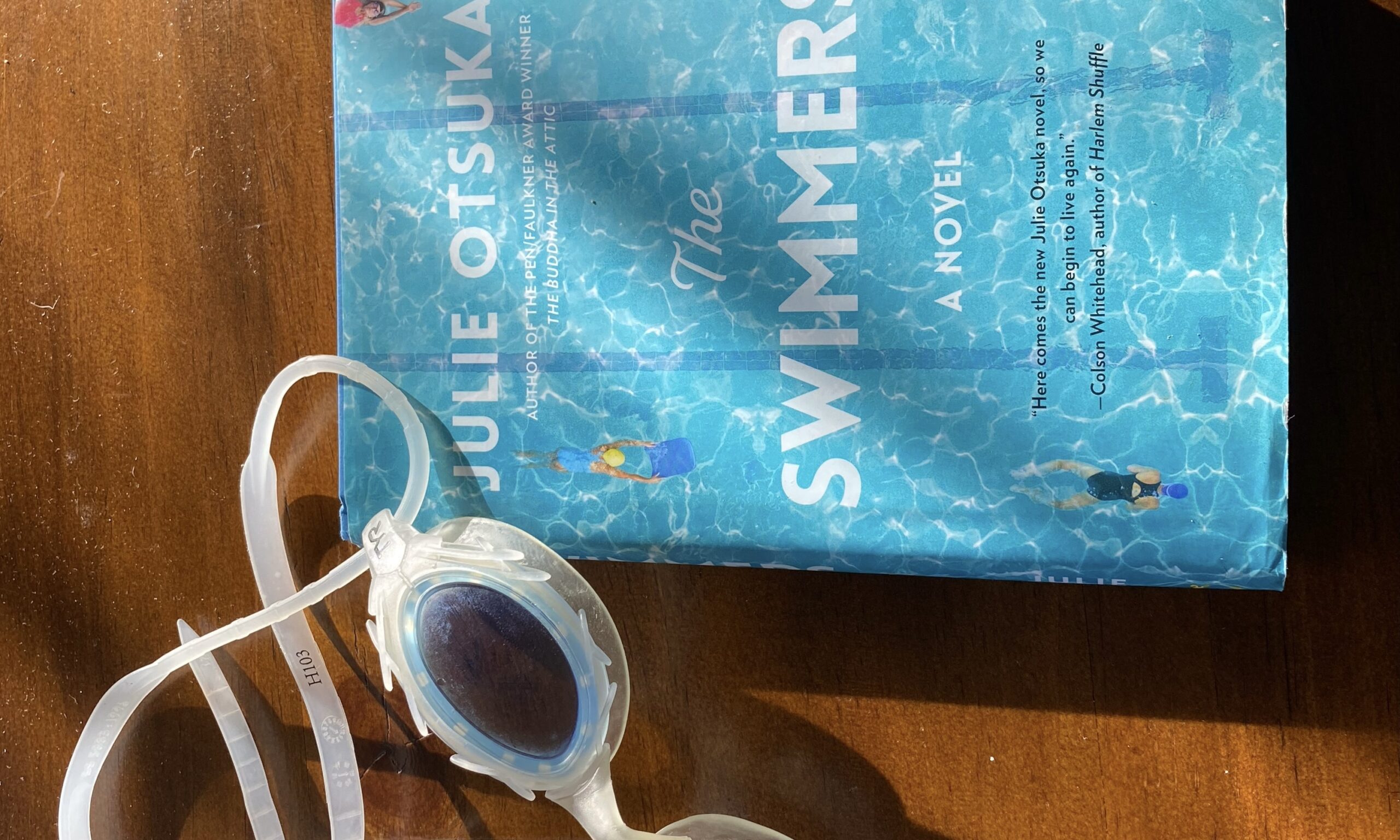

Otsuka is the award-winning author of three novels: The Buddha in the Attic, When the Emperor was Divine and her latest, The Swimmers. She publishes, on average, one book per decade, which is why she’s attained cult-like status among superfans like me. Each of her books features skilled storytelling, detailed world-building, unexpected points of view, and deeply sympathetic characters. But what truly distinguishes her work, what drives me to hero worship, is her heat-seeking eye for detail, emotion-soaked prose, and linguistic dexterity. Otsuka’s sentences sparkle like perfectly-cut diamonds.

Look, I realize this sounds like hyperbole. But consider this passage: “Alice stares down at the painted black line on the bottom of the pool while swimming her laps as scenes from her childhood flash one by one through her head. I was jumping rope in the desert. I was looking for shells in the sand. I was checking under the raspberry brush to see if the chickens had laid any more eggs. And even though she will not remember a thing once she returns to her life above, for the rest of the day she will feel enlivened and alert, as though she had been away on a long trip.”

Alice, we already know, is a retired lab technician in the early stages of dementia. As she swims, her mind unspools with slivers of the childhood she spent in a Japanese-American incarceration camp. This is just one of the many brilliant, painful paradoxes at the heart of The Swimmers: Alice can only access her memories while she swims. So we come to understand who she is and what she has endured at the same time as her mind is unraveling.

The Swimmers is a lean book, only 192 pages, with a premise that appears simplistic at first glance: how does a group of recreational swimmers react when a mysterious crack starts to form in their pool? But Otsuka creates a vast, multi-dimensional community that occasionally includes us, the readers. She divides her characters into three groups: the fast-lane “alpha people of the pool,” the “visibly more relaxed” medium-lane people, and the slow-lane people who “tend to be older men who have recently retired, women over the age of forty-nine…and the occasional patient in rehab.” To further differentiate them, she uses off-hand descriptions like “normally fearless Gary in lane four,” “water walkers” Francesca and Meg, and “afternoon regular Randall.” Through these mundane details, Otsuka not only illuminates the ordinary routines that shape our lives and personalities she also makes them seem extraordinary, even otherworldly.

In The Swimmers, Otsuka offers a provocative, moving, intimate meditation on mothers and daughters, growing up, growing old, losing your way, losing your mind, and facing the inevitability of death. Through her remarkable writing, we are invited to simultaneously bear witness and reflect on our own mortality.