I admit it: I used to swoon over the pictures of William and Harry in YM magazine back in the 90s. The same age as William, I casually but eagerly followed the boys’ public lives. My cousin and I were barred from the TV room when our mothers tuned in to watch Diana’s explosive interview in 1995, but we snuck back downstairs to eavesdrop. I woke early to watch both royal weddings. I pre-ordered my copy of Spare. And while I certainly get the “No more woe-is-me overshare” criticism, I also feel genuinely sympathetic for Harry, who has spent his life under intense and often cruel media scrutiny. As I read his memoir, it wasn’t the hot moments, which were leaked early (the broken dog bowl, the frostbitten “todger,” conniving Camilla, lip gloss gate, etc), that ultimately captured my attention. Rather, I was left with an overarching sadness for his burdens. Despite nearly infinite wealth and privilege, Harry never knew a happy home. The royal family is Tolstoyan, undoubtedly—unhappy in its own way—and whether or not they, individually and collectively, deserve this public censure from Harry’s memoir, I will leave to the British people. I do think, though, that it’s worth reflecting on one particular role that memoir plays—as a personal tool to grapple with identity.

Throughout the book Harry emphasizes conjoined themes: the lasting trauma of his mother’s death and the malignancy of the British tabloid press. He traces not only the effects of his mother’s death on his life, but also his struggle to accept its finality. And little in his world—save some found peace in Botswana and some stretches during his time in the Army—is free from the press’s poison. Life, of course, is never this consistently thematic. But memoir demands themes. It demands lessons and revelations and relatable metaphors. Every chapter, every vignette must have purpose. Each memory must build on the last and connect to the whole. In many ways memoir shares more DNA with the novel than with autobiography. And yet the great challenge with memoir is that it must read as factually credible. Harry’s impressive recall of physical places—the halls of Balmoral, a river in Botswana, and the sands of Afghanistan—is truly transporting. (He admits his recall of conversation detail is much less so. But so what if he can’t remember exactly what “Willy” said to him in the gardens at Frogmore? He remembers exactly how his brother’s words felt—and what’s more lifelike than that? Our lives may not be conveniently thematic, but for most of us our memories are retained better by emotion than by mimeograph.) I suspect that it’s precisely because the memoir genre requires this combination of precise detail and overarching themes that it ends up acting like a Freudian therapist for the memoirist. What are the pumps and pistons that explain not only why we did what we did, but also why we keep doing those things?

Harry’s ghostwriter is the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and novelist, J. R. Moehringer, who is known for penning literary memoirs for both Andre Agassi and Phil Knight. In the acknowledgements, Harry thanks Moehringer, adding that he “spoke to [Harry] often and with such deep conviction about the beauty (and sacred obligation) of Memoir.” Did Harry require convincing that what he was doing was beautiful? A sacred obligation, even? Do public figures have an obligation, whether sacred or profane, to tell their stories? I think we all have an obligation to ourselves in the very least (and thereby the lives of those we most directly, personally impact) to trace any themes of trauma so we can stop, as much as is possible, the passing down of such traumas. But does that obligation extend beyond the walls of our home, however fortified those walls may be? Maybe. What I am certain of is that the vitriol stirred up by Harry’s memoir is truly stupefying. He’s hardly the first royal to reveal some dark underbelly of the Firm. Edward VIII, Wallis Simpson, and Sarah Ferguson all wrote memoirs after departing the family. Both Diana and Charles were later revealed to have contributed extensively to their own biographies. But Harry and Meghan appear to remain particular targets for hatefulness. And why not? How could we expect anything different, when Britain has never actually reckoned with colonialism, when the overtly racist tabloids sway like some sword of Damocles above the Monarchy? I doubt this book will usher forth a kairos for Britain, but perhaps Harry’s courage in writing it does suggest a sacred obligation after all.

As regards the writing itself, I was absorbed in Harry’s adventures for long stretches of time. The short chapters clipped right along yet lingered after I’d closed the book. Nevertheless, the prose was often distracting. Or maybe I’m just more prone to noticing: I left teaching a year ago to become a ghostwriter for a book company that publishes non-fiction and memoir. I love the work, but—for better and worse—it’s made me more attuned to the craft of ghostwriting. I see the brushstrokes, I know how the various dials turn behind the green curtain. In Spare, for instance, literary references abound, and Hamlet predictably makes a few appearances. Though Harry does express an interest in poetry, reading literature was never his forte. And, at the very end, a hummingbird becomes a convenient metaphor for Harry himself. It’s a lovely scene, but distractingly on the nose.

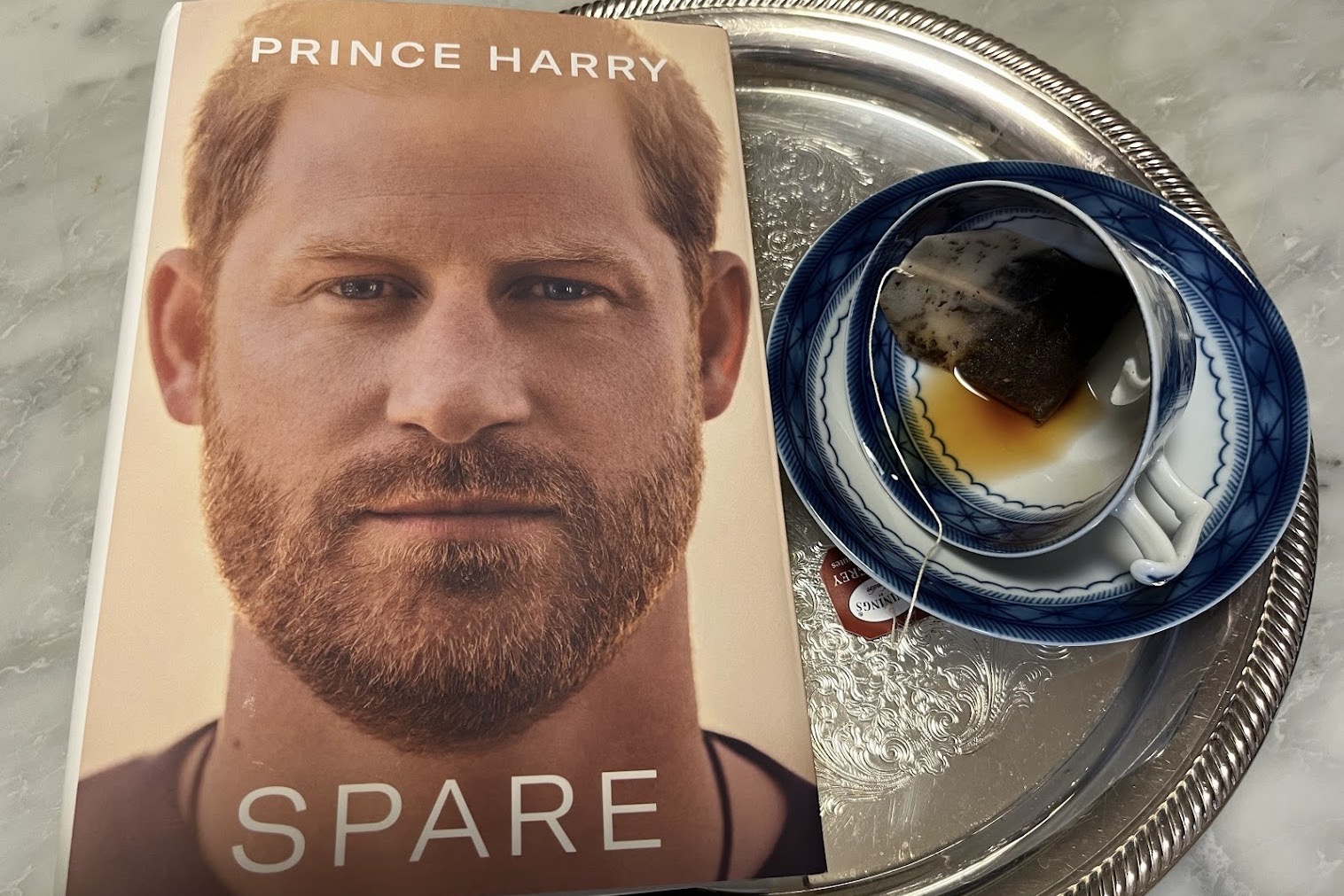

And that, of course, is where memoir and the stuff of our lives part ways yet again. After the memoirist has wrestled his demons, it is ultimately his story, not his life, that must win the final battle. We want our neat and lyrical ending. We want our misty-eyed denouement. I do recommend Spare, but only if you’re willing to approach it with a spirit of generosity. And if you, like me, still find that the handsome face on the cover triggers a girlish crush, please read it in any spirit you like.