There’s this moment that always happens when out-of-town friends visit me in Los Angeles for the first time. Guidebook in hand, camera ready, they demand– despite my gentle suggestions otherwise– a visit to Hollywood. That’s when I know the moment is coming.

This moment– it can happen while we are looking for (nonexistent) parking. Sometimes, the moment holds off until we’ve stepped out of the car, onto litter and dried vomit: the moment when those dreams of old, glorious Hollywood vanish, and my friends are left with the reality of the real Hollywood– a tourist-fueled pit that is often ignored by social services, where people are left to live– and die– by their own devices. When people picture the Hollywood made famous and glamorous by the silver screen, they’re really thinking of the Promenade in Santa Monica, or the few shopping centers and pristine beaches open to non-celebs in Malibu. They are not thinking of actual Hollywood. Actual Hollywood has a great deal more in common with the science-fiction epic Escape from L.A. than the heartfelt musical Singin’ in the Rain.

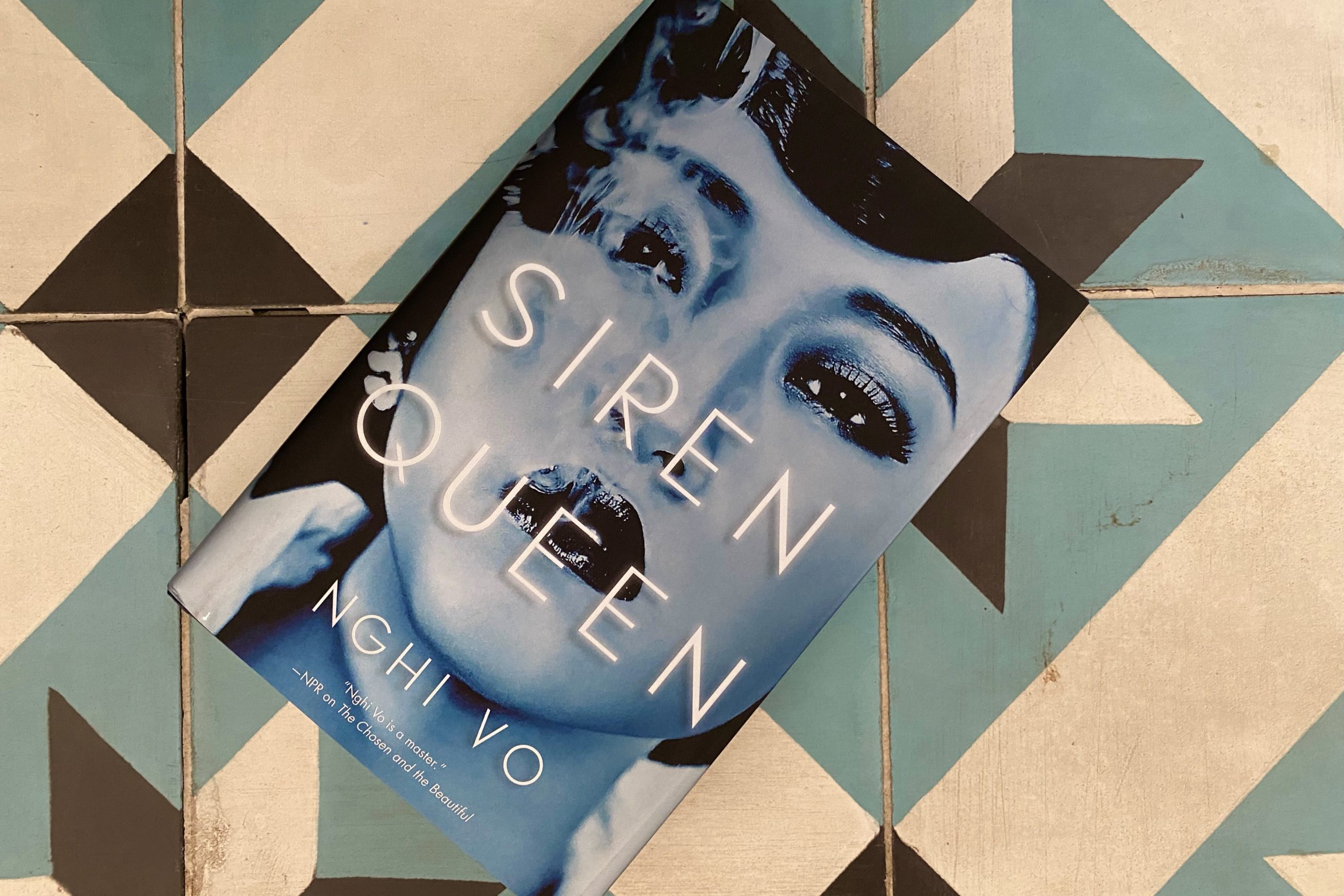

I was reminded of this misguided expectation of Hollywood when reading Nghi Vo’s vibrant and meaningful magical realist novel Siren Queen. Written like a memoir, Siren Queen is the story of a queer, Asian-American actress Luli (with more than a few similarities to real-life old Hollywood Asian American star Anna May Wong, who only just recently was awarded commemoration on a quarter) as she tries to make a name for herself in pre-Code Hollywood. This is a Hollywood that has very little interest in the inner lives or wellbeing of its white actresses, much less those of color. Luli’s drive for fame is a pursuit to be seen, to be acknowledged as more than just her race. As she tries to come up with the words to explain her ambition to a fellow (white) actress, she finds that she cannot: “They [the words] locked up in my throat, about being invisible, about being alien and foreign and strange even in the place where I was born, and about the immortality that wove through my parents’ lives but ultimately would fail them. Their immortality belonged to other people, and I hated that.” The struggles of Luli’s family– consistently “othered”– is a throughline that follows Luli in her rise to stardom. The daughter of Chinese immigrants in Hungarian Hill, Luli must deal with the expectations and disappointments of her own family as she tries to pursue her calling. It is the interpersonal relationships in Siren Queen that add a realistic, warm tone to an often fantastical story.

In Siren Queen, the monsters are not purely metaphorical. Real magic permeates the Hollywood studio system, where girls are (literally) chewed up and spit out. When Luli finally has her “shot,” a meeting with studio bigwig Oberlin Wolfe, “one of the most powerful men in Hollywood,” he surveys her more as a piece of raw meat than a human being. Their meeting would sound familiar to Marilyn Monroe and many modern day Hollywood starlets, but with a more canine twist– as Wolfe lives up to his name. “He looked deep into my eyes, and then I saw what was wrong with his. The pupils never moved, either to shut the light away or take it in. It prickled something in my hindbrain, telling me that if Oberlin Wolfe had ever been human, he certainly wasn’t any longer.” While she manages to escape the actual fangs of this studio maven, it is only the beginning of Luli’s travails. We become enraptured in Luli’s tale of survival as she navigates the cruel, patriarchal and racist system meant to break women down and reshape them. (Or, on certain days of the month, quite simply– and literally– hunt them.) Even Luli, for all her cunning, cannot escape unscathed.

Luli herself is a complex character– likable but also maddening in her pursuit of fame. And whether she has found “success” embodying, as the title itself gives away, a monstrous “Siren Queen,” is up for us to decide. She’s famous and rich, yes, even a star (the scene where Luli reaches peak stardom is a beautiful blending of magical realism and taut emotion). However, Luli is famous for playing a monster, a monster that provokes and perhaps promotes racist stereotypes. And yet, that is her choice. No one, as the studio heads who try to replace Luli realize, can play the monster quite like her.

There are no easy answers in Siren Queen, but there are plenty of questions, and more than a few lessons, all packed deliciously, devilishly, in this fantastical send-up of Hollywood. A gate-kept, hateful Hollywood that for many still exists.

If only Luli could see her beloved Hollywood now. I have a feeling she’d be sporting an enchanting smirk– and would demand to see her own star on the Walk of Fame.