When the Berlin wall fell, my immigrant father-in-law could finally go home to his native Slovakia and bring his beloved friends for visits to Chicago. We reveled in the story of his best friend’s visit: Silvo, a successful architect, wept openly at the abundance of fresh produce in the supermarket. This is the kind of story Americans like best: visitors or new immigrants brought to their knees by our treasure trove of resources, as we proudly bear witness.

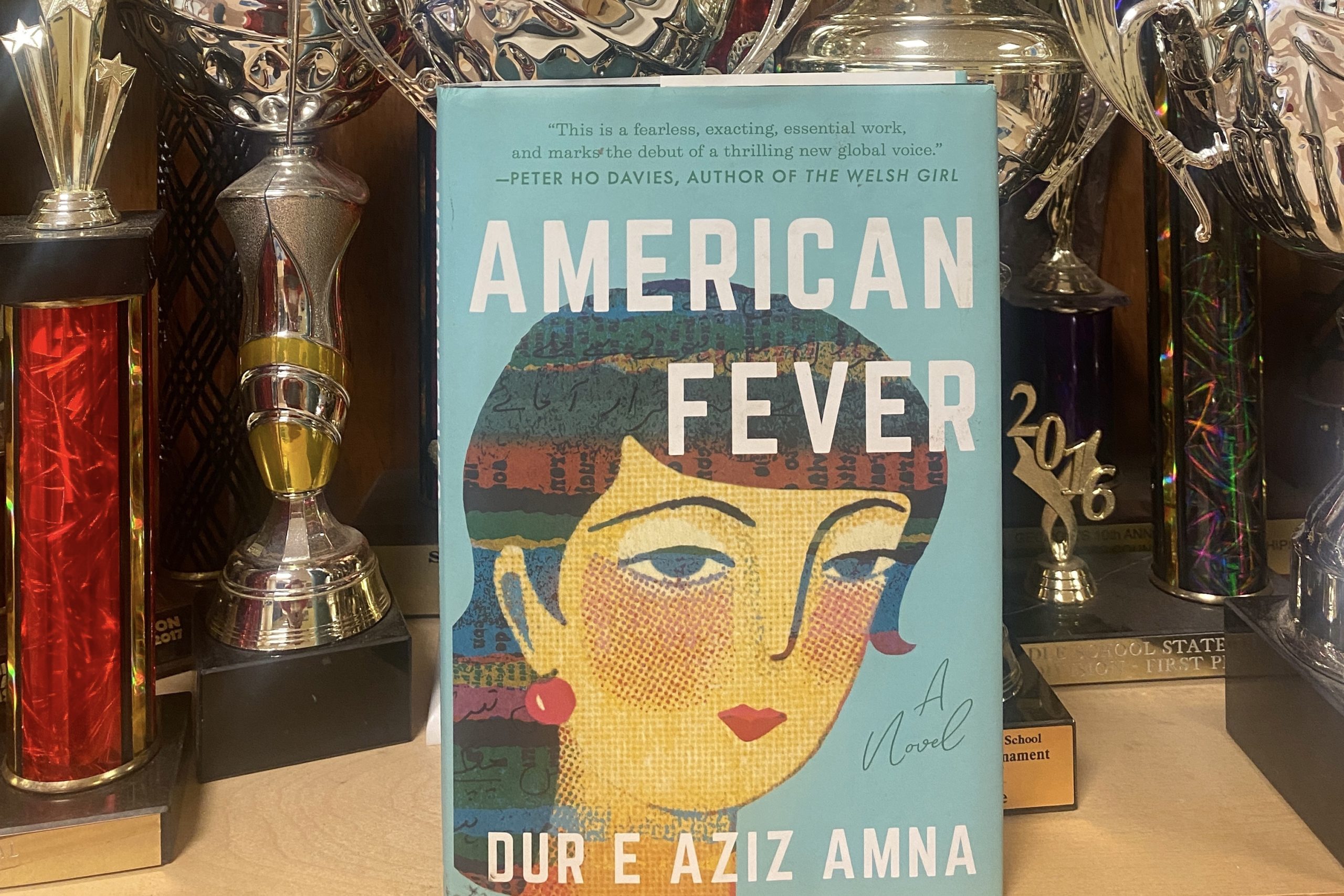

In Dur E Asiz Amna’s memorable debut novel, American Fever, Hira is a Pakistani teen who wins a scholarship for a student exchange program in the States during the Obama administration. While her peers are excitedly making plans to join host families in New York, Hira learns she will be spending the year in a rural town outside of Eugene, Oregon.

If this novel was designed to buoy American spirits in the wake of global disaster and uncertainty, we might find ourselves reading about a girl who learns to love Judeo-Christian culture, McDonald’s, and, perhaps, a boy named Justin. Instead, the narrator forms a reluctant alliance with Kelly, a pretty single mom, who hopes an interesting house guest will build bridges with her diffident teen daughter, Amy. Hira heads off to Lakeview High where she is viewed with suspicion, forced to play volleyball, and only really feels comfortable with fellow outsiders like her friend Hamid, who says of his new, temporary countrymen, “If they only knew the biggest terrorist in Oman is my mother.”

Amna deftly laces this stranger-in-a-strange-land tale with lots of humor and finely-drawn portraits of rural Oregonians. Kelly is far from a stereotypical small town mother and Amy’s story shifts and grows in subtle ways that lead to a lovely coda near the end. Even Kelly’s right-wing, video-game-loving-boyfriend-turned fiancée, Ethan, is given some nuance.

Yet we spend most of our time with Hira—beautiful, challenging, complicated Hira—whose sardonic stance is echoed in the ways her body betrays her during this sojourn. She loses weight, grows pale, and finally realizes that her testing positive for TB and still continuing on to the States showed some truly poor parenting on the part of her beloved Ammi and Abbu. Throughout the novel, Hira flip-flops on her parents, on Kelly and Amy, and on American culture, vacillating between extreme positions that might get her mistaken for a U.S. senator or an American teenager.

Eventually, Hira does expand her worldview when all sorts of new experiences knock her out of her surety. There is a bloom of romance (no local Justin but a handsome NYU boy from home) and a conversation with Kelly’s German mother that makes an impact: “I know this sounds odd” she tells Hira, “but leaving doesn’t have to be a tragedy. It can be quite freeing, to never be at home anywhere.”

Amna’s main character is not always pleasant to be around but often funny as hell, with observations as winning as the pretty, pasted-on smile with which she disarms her new community. Hira is as overwhelmed in the grocery store as that Slovakian architect visiting my father-in-law, but more by the audacity than the abundance: “Kelly saw me looking around and laughed, no doubt delighted by what she thought was my wonderment at the bounties and excesses of America. But Lord, it was 2010, and everyone knew about America, the place that would upsell you on the thread count for your deathbed.”

Pakistan rarely gets the gentle treatment from the west that it receives in American Fever. Asiz frequently hints at the more restrictive culture that awaits Hera when she returns home, yet focuses on the importance of an unforgettable place, inhabited by wise and loving people missed beyond measure. This rewarding and distinctive tale reminds us that our homeland always makes a mark on our soul, despite the distances we travel in an attempt to become someone new.