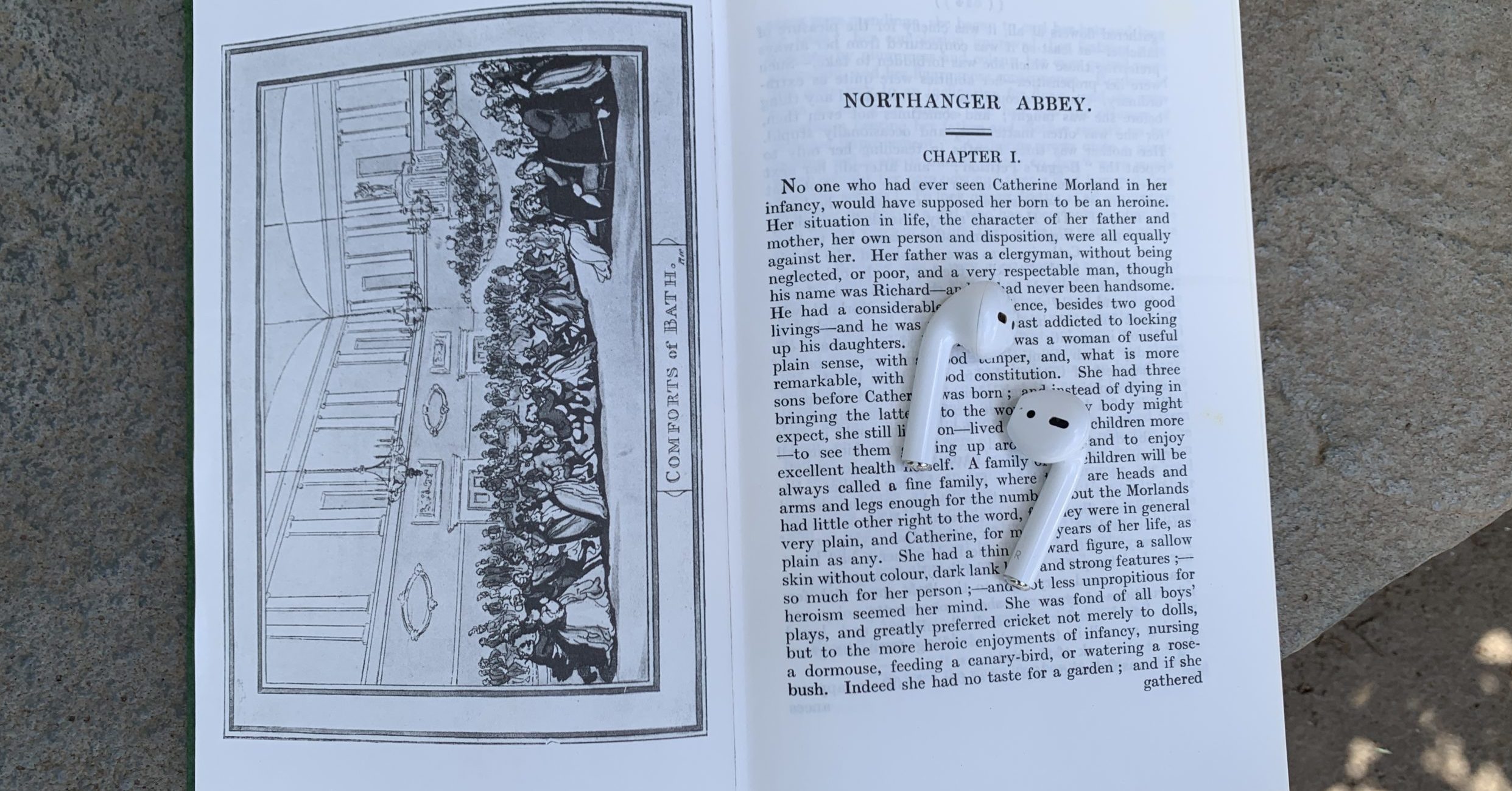

Last summer I listened my way through Jane Austen. A longtime re-reader, but first-time audiobooker, I found the experience delightful. Scholars have compared Austen to Shakespeare in her ability to capture a character efficiently and memorably, and hearing those voices––like hearing Shakespeare––just feels right. If you have not yet experienced this pleasure, I highly recommend it.

Northanger Abbey is Austen’s first completed novel, but it wasn’t published until after her death in 1817. Unsurprisingly, therefore, it captures all the energy and playfulness of a youthful author. In it Austen explores the coming-of-age of her youngest and perhaps simplest heroine: the “unexceptional” seventeen-year-old Catherine Morland, lively in both spirit and imagination but utterly guileless. Like most young people her age, then and now, she is ready to soak up the world around her and learn as much as she can. For the first half of the story we follow her adventures in the fashionable spa town of Bath, where she encounters two very different sets of siblings, each instructing her–indirectly and directly–about herself and the world. John and Isabella Thorpe are pitch-perfect examples of obliviously selfish young people: materialistic, idiotic, and reckless. On the other hand, Henry and Eleanor Tilney provide Catherine with kindness, wit, and, among other lessons on beauty, how “to love a hyacinth.” It is the Tilneys who eventually invite her back to their country estate, the eponymous Abbey, for an extended stay. Catherine, a passionate reader of Gothic novels, can barely contain her joy to be the inhabitant of Northanger, imagining its probable “long, damp passages, its narrow cells and ruined chapel” and she can “not entirely subdue the hope of some traditional legends, some awful memorials of an injured and ill-fated nun.” While the home proves disappointingly modern, a few dark corners provoke Catherine’s vivid imagination and rather teenagery desire for a scandal. When she assumes a grisly explanation for the Tilneys’ severe patriarch, General Tilney, and his mysteriously dead wife, Austen brilliantly shows us that not everything is black and white, and every family does indeed have its skeletons. Catherine isn’t entirely wrong about the General–it’s just that his skeleton is that of punitive and narcissistic greed, rather than uxoricide. Her naivety takes a hit, and the world becomes both better and worse than she’d imagined it to be.

Like all of Austen’s families, the Tilneys are a cast of both the repugnant and the laudable, and the General’s youngest son, Henry, clearly ranks among the latter. Playful, charming, energetic, and well-read, he is a delightful, scandal-free lover and my current favorite Austenian hero. He also plays an appealing foil to John Thorpe, who similarly pursues Catherine while they remain in Bath. Thorpe, obsessed with money, carriages, driving fast, and avoiding his younger sisters, reminds me of one of those bros on The Bachelorette, who can’t figure out how to talk to a woman, so he bloviates about protein powder with the other guys. Both we and Catherine feel relief each time she escapes him. He also makes her and our falling in love with Henry seem like the easiest thing in the world.

While much of the novel is not unusual for Austen, it is surprisingly meta. Austen frequently addresses her readers and their expectations of her plot and heroine, leaving the details of one conversation between Henry and Catherine up to “[her] reader’s sagacity.” In the final chapter, she even comments that the other characters’ anxiety for Henry and Catherine’s union can hardly extend to the readers, since they “will see in the tell-tale compression of the pages before them, that we are all hastening together to perfect felicity.” Between Austen’s winking acknowledgement that yes, I know what you expect, dear readers–so watch me both toy with and gratify those expectations–and her absolute capturing of what it is to be a 17 year-old young woman, the whole novel feels amazingly fresh and contemporary. She sharply satirizes absurdities in the fiction of her peers, while simultaneously honoring readers and novels of all genres. And she critiques an over-active imagination fed only by literature, while simultaneously proving that virtue in action often depends on a healthy imagination.

It’s not a perfect novel, and Austen is still clearly finding her literary footing, but Northanger Abbey does produce in its readers–at least it did for this one–perfect felicity.