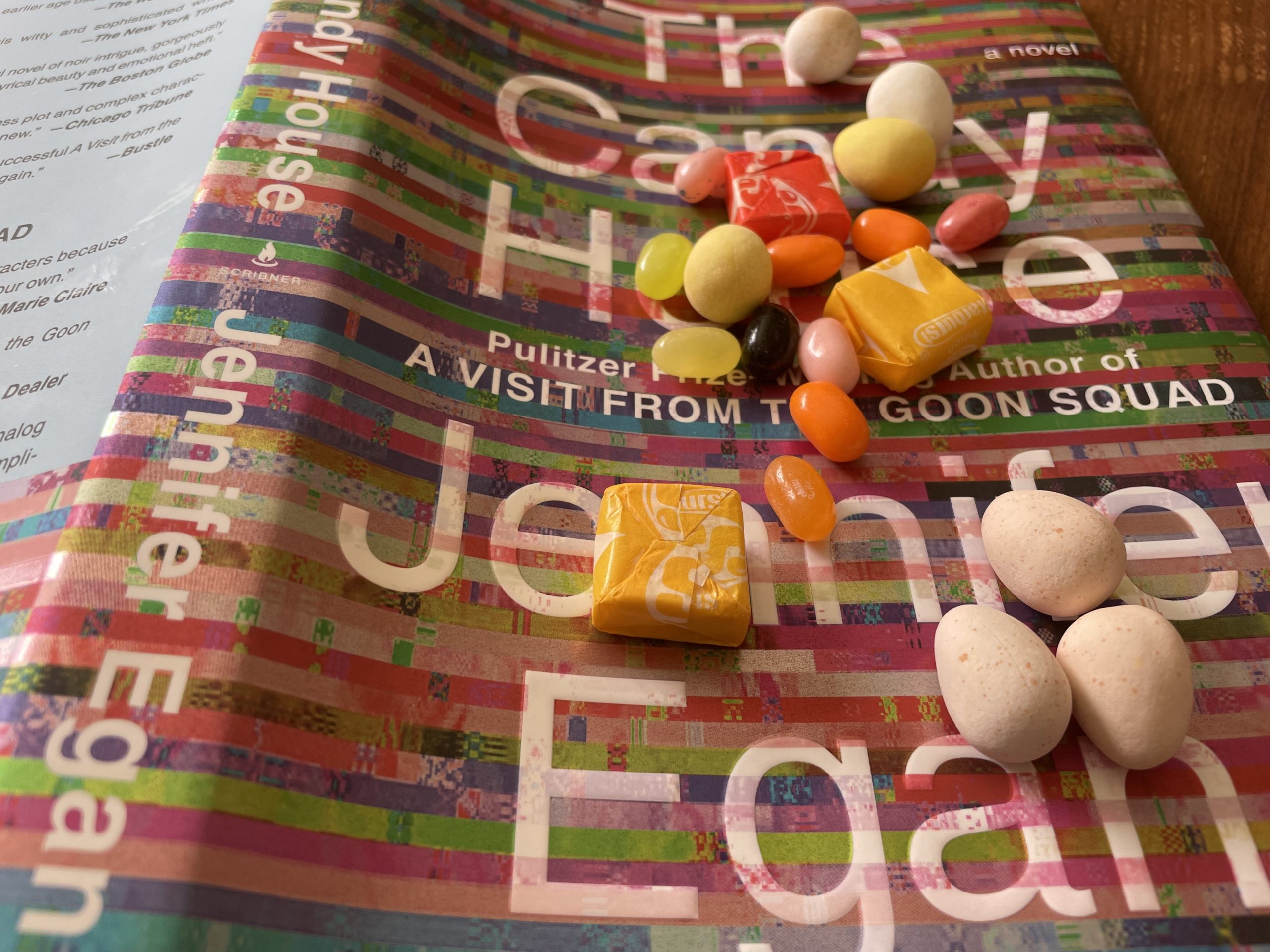

Jennifer Egan’s The Candy House is a delight. As I devoured this book, I imagined each chapter as a uniquely-wrapped confection with a provocatively unsettling center. At the same time, I understood the overall narrative to be intimately networked, mirroring the different technological innovations that Egan imagines, if not foretells.

Technologies are as important to this novel as the characters who create, embrace, and elude them. For example, Bix Bouton is a Zuckerberg-like innovator who operationalizes an algorithm involving the so-called “affinity charm,” becoming rich and famous while changing the digital and real worlds forever.

As the novel opens, Bix needs a new idea, so he attends a gathering of Columbia professors where he plunders at will, appropriating an idea related to the externalization of memory. From there, Bix builds his second act: “Own Your Unconscious” – an external hard drive in the shape of a cube where people can download their memories into a digital collective for all to mine. In Egan’s deft storytelling, Bix’s innovation feels like both a shocking impossibility and an eventual inevitability.

Every single chapter in The Candy House is a stunning, satisfying experience – but one chapter is particularly wonderful. Featured in The New Yorker back in 2012 under the title “Black Box,” the story has been retitled “Lulu the Spy, 2032” for The Candy House.

Lulu is a “citizen agent” on a mission so dangerous that she can carry no devices; instead, she has become the device: different signaling mechanisms have been implanted inside her with the intention of leading her team to its target while recording her thoughts. Egan presents Lulu’s “diary” from her mission in the form of thought-tweets, beautiful little narrative bursts:

Hindsight creates an illusion that your life has led you inevitably to the present moment.

It’s easier to believe in a foregone conclusion than to accept that our lives are governed

by random choice.

A smile is like a shield; it freezes your face into a mask you can hide behind.

A smile is a door that is both open and closed.

In the new heroism, the goal is to transcend individual life, with its petty pains and loves,

in favor of the dazzling collective.

The “dazzling collective” is pretty language to describe the effacement of self in the digital age, resonant with the symbolism of a candy house deep in the forest that may appear a lifesaver but in fact brings death. Although they look enticing to those who have lost their way in the proverbial forest, candy houses are little more than false memory palaces, seductive traps that soothe as they threaten. In the end, Egan’s many candy houses melt away under humanity’s need to be physically safe, authentically seen, actually loved, and really known.