The Transit of Venus is an uncompromising, breathtaking novel, difficult to crack, one that requires focus, a momentous work for many writers who admit they had to come at it more than once before they absorbed its full impact. Published in 1980 by the brilliant Australian author, Shirley Hazzard, the story of two orphaned Australian sisters who arrive in England in the 1950s seems both old-fashioned and dazzlingly modern. The set-up, reminiscent of Henry James with a dash of fairytale, imagines a clash between post-war Britain and an Australia devoid of culture. The book contains social and political ironies observed by its prescient narrator and includes a series of romances that examines all varieties of love while existing as a deeper commentary on power, morality, and fate.

We are drawn especially to the fascinating, flawed Caro Bell, whose desire to live a noble life is complicated by her childhood in thrall to an older half-sister, a Dickensian villain equal parts hilarious and horrifying; the limitations and indignities stifling all of the book’s women; and the devastating consequences of her own heart’s choices. Though accomplished in the world of international politics, Caro is stymied, and her life is shaped by the men in it: a shabby astronomer, Ted Tice, whose hopeless, enduring love is imbued with the mythology of Orpheus and Eurydice; the charming playwright Paul Ivory, whose magnetism and betrayals drag her perilously off course; and Adam Vail, whose American candor, wealth, and pursuit of justice allow her a meaningful period of happiness. Though we follow Caro’s sister, Grace, into her marriage with a pompous bureaucrat, it is Caro’s many reversals of fortune that propel the novel.

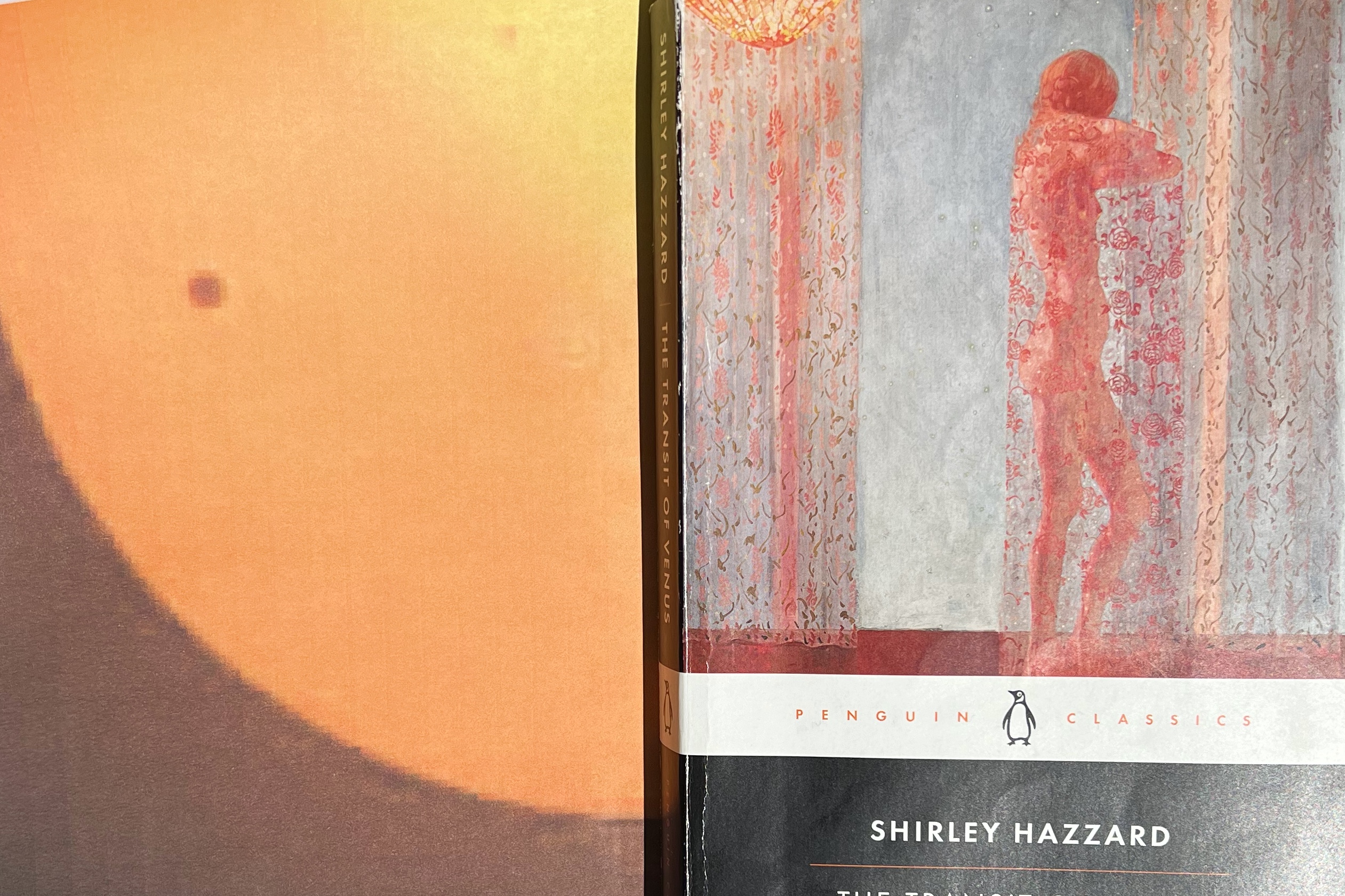

As the transit of Venus, an astronomical event that occurs eight years apart every 243 years, twice moves the black dot of Venus across the sun, the book brims with pairs and echoes: the sisters, the tremendous storms that bracket the narrative, capsized boats, planes streaking across the sky, fathers and sons, ill children, bombs both literal and metaphorical, ruins, affairs, secrets. On every page, Hazzard hones her writing with a poet’s vitality and an editor’s rigor. She excels at a grand sweep: “Around [her] these impressions passed in ritual rather than confusion: the simultaneous preoccupation of girls with love and dresses, the men with their assertions great and small, the women all submission or dominion; an imbalance of hope and memory, a savage tangle of history.” Her similes are astute: “Grace couldn’t bear his good manners or the thought that this man in his crisis indulged her as a dying officer might joke to a rattled subordinate on a battlefield” and her metaphors witty: “…he cut the oval sweep of a watermelon. His scalp was smooth except for a splaying of strands over the crown; his eyes, a hurt blue, were the eyes of a drunken child.”

Hazzard is equally at home in the specifics of human interaction—our fierce longings, our fatal mistakes, our self delusions, our struggle for integrity—as she is in the wide scope of humanity—our wars, our ancient monuments, our atomic bombs—and in the amorality of the natural world—its deluges, its stars and planets, its indifference to our tragic destinies. It is rare that I finish a book, turn to the first page, and read it again in its entirety, but The Transit of Venus exerted that demand on me.