A few months ago, talking with my friend, Antoinette, I share how excited I am to be traveling to Ireland this summer as part of my MFA in Creative Nonfiction.

“You must read A Ghost in the Throat,” she exclaims. First, I think I have misheard her. Frog in your throat?

“A what?” I ask.

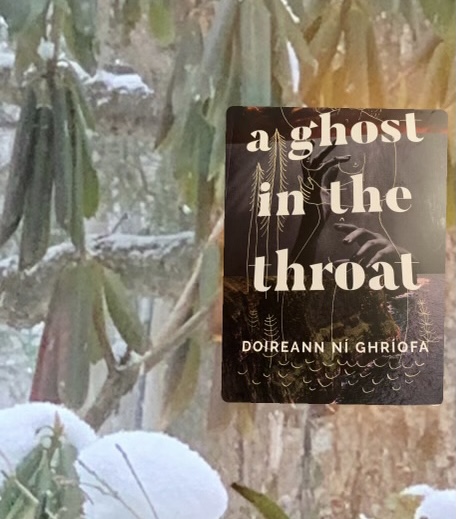

“A Ghost in the Throat by Doireann Ní Ghríofa,” she says again. “It’s a memoir. It’s speculative non-fiction. It’s everything you love.”

Once we hang up, I find the book quickly in my library’s e-book collection, and I start reading.

“THIS IS A FEMALE TEXT.

This is a female text, composed while folding someone else’s clothes. My mind holds it close, and it grows, tender, and slow, while my hands perform innumerable chores.”

I’m hooked. The author weaves a tapestry of motherhood, the day-in, day-out relentless and tedious and miraculous work of raising children, of nursing infants, of making lists, of pumping breast milk, of wondering who we become once we have children. She recalls the story of one of the last noblewomen of the old Irish order, Eibhlin, whose story she learned in grade school, a woman keening over the body of her husband, ambushed by English soldiers. She is smitten by Eibhlin’s story, characterizes herself as having a schoolgirl crush on the woman who composed the Caoineadh, a long, lyric poem, first passed down first through the oral tradition. The poem is a paean to love and motherhood and passion and grief and loss. She invites Eibhlin’s voice to haunt her throat.

Over time, exhausted though she is as a mother to three, she grows obsessed with learning more about Eibhlin. In the same way that motherhood is comprised of endless circles of need, so Ghríofa immerses herself in excavating Eibhlin’s biography, to find what can be found about the real woman’s biography—beyond the poem—first in libraries and university reading rooms, then in visits to in town archives. Her research is augmented by her own imaginings, by her powerful identification with Eibhlin.

Ghríofa speculates about Eibhlin’s life as she sits tethered to a breast pump; she spins another identity for herself—exhausted mother of three boys—in her meanderings, first imaginary and then real. Toting her toddlers, she travels to places Eibhlin lived, listening for her voice. She searches documents, looking for evidence that her heroine’s children lived. Her investigation results in a blend of biography and memoir as well as a powerful meditation on motherhood.

What happens to our own identity when we have children? We put their needs first. Our priorities shift. Ghríofa writes:

“Every day, I battle entropy, tidying drooped toys and muck-elbowed hoodies, sweeping up every spiral of fallen pasta and every flung crust, scrubbing stains and dishes until no trace remains of the forces that moved through these rooms…As I clean, my labour makes of itself an invisibility. If each day is a cluttered page, then I spend my hours scrubbing its letters. In this, my work is a deletion of a presence.”

I think about women whose lives went unrecorded through history because they were too subsumed in motherhood to write or paint or leave a record of their lives. In reclaiming Eibhlin’s life, in posing questions, creating a version of a real woman who lived beyond the stanzas of a poem, is Ghríofa creating an identity for herself, for all women?

Eibhlin’s life is a counterpoint, echo, ghost of Ghriofa’s existence. There are moments when the two seem to merge, bridging the centuries, despite the difference in their circumstances. Both love fiercely. Both mourn and grieve. Both are women, whose lives, had there not been an epic poem celebrating one and this powerful memoir-esque book written by the other, might have vanished, unremarked. Yes, Eibhlin is a folk heroine, whose stanzas capture her adventures, but what Ghríofa’s quest excavates is the folk heroine’s humanity, her motherhood, her powerlessness in the face of her beloved husband’s murder. Threaded through the text is Ghríofa’s exhaustion, the utter mind-numbing, endless fatigue of mothering. That these two realities are spun together is part of the book’s power.

Years ago, before Women’s Studies was even an acknowledged major, I took classes in a small butter-yellow building behind a pizza parlor with a brilliant professor, Harriet Chessman, who taught A Room of One’s Own. Around a seminar table, so much of our lives in front of us, a group of feisty young women felt enraged when we realized that women had been written out of so much of history. Without money and a room of one’s own—or, I might add, great childcare—women have, for centuries, met others’ needs before even attempting, in their exhaustion, to meet their own. While Woolf did not have children, Ghríofa and Ni Chonaill did. In this exquisite fusion of women loving fiercely three hundred years ago and today, I felt, somehow, I had re-discovered a part of myself that I had not realized I was missing. I follow my beloved professor on Facebook; she is a grandmother now and an author, but first, she was my teacher. Her influence on me, as a young woman, reminds me of those spirits we choose to carry with us—touchstones, amulets—whose words float up when we need them the most. We all carry our ghosts, don’t we?