If you are a mother, chances are you’ve had your share of Bad Mom Days: maybe you lost your patience when your kid had a tantrum at Target and grabbed her wrist a little too hard. Maybe you ran into the post office to mail a package and left your sleeping baby in the car. Maybe you had a really Bad Mom Day. Maybe while you were sending a quick text at the playground, your kid fell off the zipline. Maybe—during just-one-more-episode of Doc McStuffins—you go outside to get the mail and end up in a conversation with your neighbor, and when you come back, your kid is juggling the batteries from the TV remote.

Every mother has some version of these stories, though in most cases, everyone escapes unscathed.

But what if your neighbor realizes that your toddler is inside unattended and calls the cops? What if someone saw you at the playground or post office and reports you to Child Protective Services?

Then what?

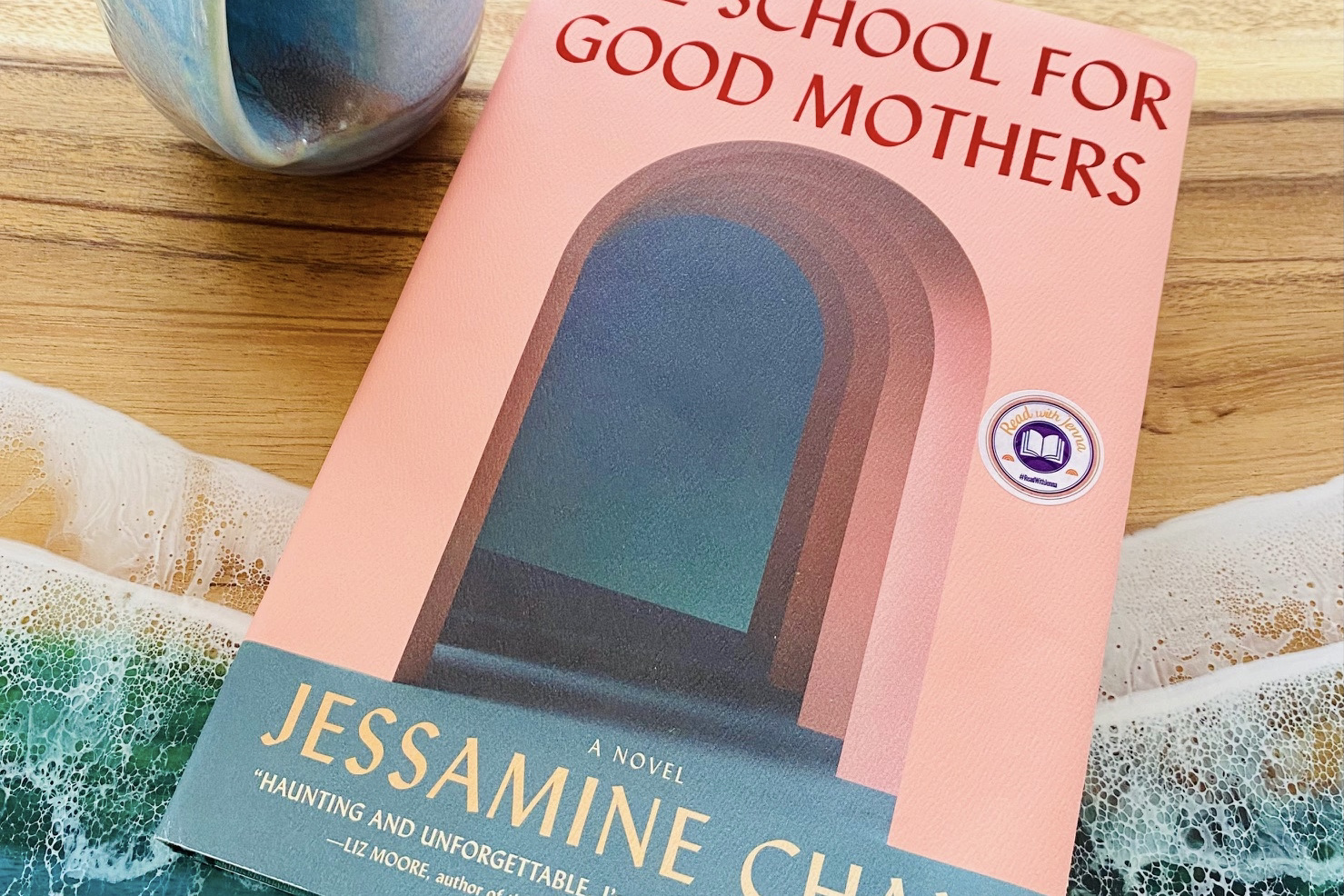

Frida Liu — the 39-year-old, Chinese-American single working mother in Jessamine Chan’s debut novel The School for Good Mothers — learns exactly what.

The book opens with the line, “We have your daughter.” It’s the police calling Frida to report that her 18-month-old daughter, Harriet, is in their custody. Frida — in a moment of sleep-deprived desperation — leaves Harriet in her ExerSaucer so she can run out for coffee. Then she remembers she needs a file from her office; while there, she checks her email. A quick coffee run turns into two and a half hours. A neighbor hears Harriet crying and calls the police.

Clearly, Frida had a huge lapse in judgement. But does that make her a bad mother? Harriet is removed from her custody while Frida is placed under 24-hour surveillance in her home, with supervised visits that will determine her fate as a parent. It is all very black and white: good or bad, fit or unfit. What is ignored are the varying shades of grey that make us human, and therefore, breakable: Frida’s ex-husband left her soon after Harriet’s birth for a much-younger Pilates instructor. Frida is depressed and sleep-deprived. Harriet has recurrent ear-infections and cries constantly. Frida has no babysitter despite working a deadline-sensitive job. Her parents live across the country. She has no close friends.

The judge does not consider these factors when he gives Frida the choice: be sent to an experimental rehab facility for bad mothers or lose custody of Harriet forever. Which of course, is not really a choice.

The School For Good Mothers is subtly dystopian (think Handmaid’s Tale meets Orange is the New Black meets The Stepford Wives), but feels frighteningly realistic. At the “school” (prison), each mother (inmate) is given a freakishly life-like robotic doll (it cries, eats, and pukes) the same gender and age as her actual child. How Frida interacts with her robot child (a walking computer recording her every move) will determine whether or not she will receive custody of Harriet.

It becomes clear that the school’s purpose is not to help these mothers but to shame and punish them, some to the point of utter despair and hopelessness, forcing them to repeat aloud: “I am a bad mother, but I am learning to be good.” They are taught to suppress their own needs and desires, that it was their selfishness that landed them there in the first place. The data collected by the robot-children is just that: data. Either the mother behaved correctly or incorrectly. There is no in-between.

Chan’s writing is minimalist and perfectly paced. She does not push a political agenda though it is obvious that the themes of surveillance and repression echo the worst of our society. You can’t help but think about how harshly society judges mothers, and how low-income mothers, women of color, and those suffering from mental illness are particularly vulnerable to this type of scrutiny and punishment. (The novel includes a similar “school” for bad dads, where the bar for success is significantly lower).

The School for Bad Mothers stayed with me long after I finished reading. The fact that Frida’s mistake was bad enough — an isolated moment of neglect but one that could have been potentially deadly — created tension between empathizing with Frida and rationalizing the ways in which I am different from her. (I’ve never done anything that bad…right?)

But my connection to Frida prevailed as I cataloged not only the mistakes I have made in my 16 years of mothering, but also the circumstances leading up to them. Which begs the question: how can a mother — a flawed human being —ever be “good” if she is only as good as her biggest mistake?