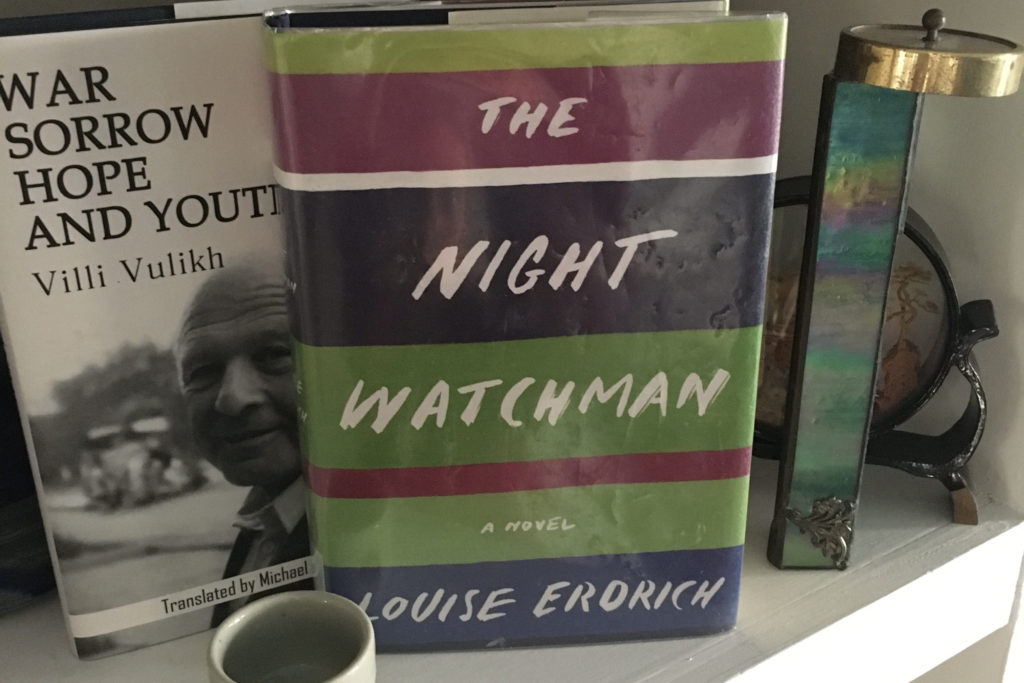

The Night Watchman, Louise Erdrich’s Pulitzer Prize-winning lyrical account of the lives of a small Ojibwe community in the 1950s offers endless gratifications. Aesthetically, the novel is a pleasure, rich with poetic descriptions infusing die-cast precision into magical realism characters rendered with insightful and judgment-free specificity, and a masterfully balanced tone—a jaded optimism that made me laugh ruefully and tear up in equal measure.

The story revolves around two sometimes interwoven threads. In one, the resourceful and resolute Pixie Paranteau searches for her missing older sister Vera, who followed a would-be fiancé to Minneapolis and disappeared without a trace. In the other, profoundly decent, beleaguered middle-aged tribal chairman Thomas Wazhask—who works as the titular watchman at a jewel-bearing factory, the town’s main employer—almost single-handedly battles the Indian Termination Bill, federal legislation that would dissolve reservations and eliminate legally recognized tribes. These disparate story threads mix and match tones. The phantasmagoria Pixie discovers in the city includes mundane evils like drugs and forced prostitution and more baroque nightmares like a Paul Bunyan-themed underwater show that may be poisoning its performers. Meanwhile, Thomas’s sections are resolutely slice-of-life, focusing on his innate goodness; his exhaustion; his devotion to his father, wife, and children; and his deep intelligence and humor. Throughout, Erdrich is extremely interested in the interminable grind of repetitive labor: the women at the factory hand-drill the jewel bearings with minute precision, Pixie’s mother matter-of-factly butchers a hunted bear for food, local boxers joyfully train for a climactic fight, and Mormon missionaries grimly cope with unexpected cold and irrepressible sexual desire.

For me, the most poignant thing about The Night Watchman is the fact that Erdrich closely based Thomas on her grandfather Aunishenaubay Patrick Gourneau and his work saving the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa from “emancipation” by the US government. Using a trove of Gourneau’s letters, Erdrich writes Thomas as a loving, gentle, deeply civilized family man—a portrait that makes this novel into a labor of love. Reading about this tribute moved me deeply. During the pandemic I translated a memoir my grandfather wrote about his experiences in the Red Army during WWII—my own labor of love dedicated primarily to my father, who passed away several years ago after guiding his dad through writing the Russian original. Diving into my grandfather’s unguarded voice for hours every day immersed me in his perspective in ways ordinary interactions never could. I can only imagine what the same experience was like for Erdrich—but I don’t have to, since its product is this beautiful and empathetic novel.