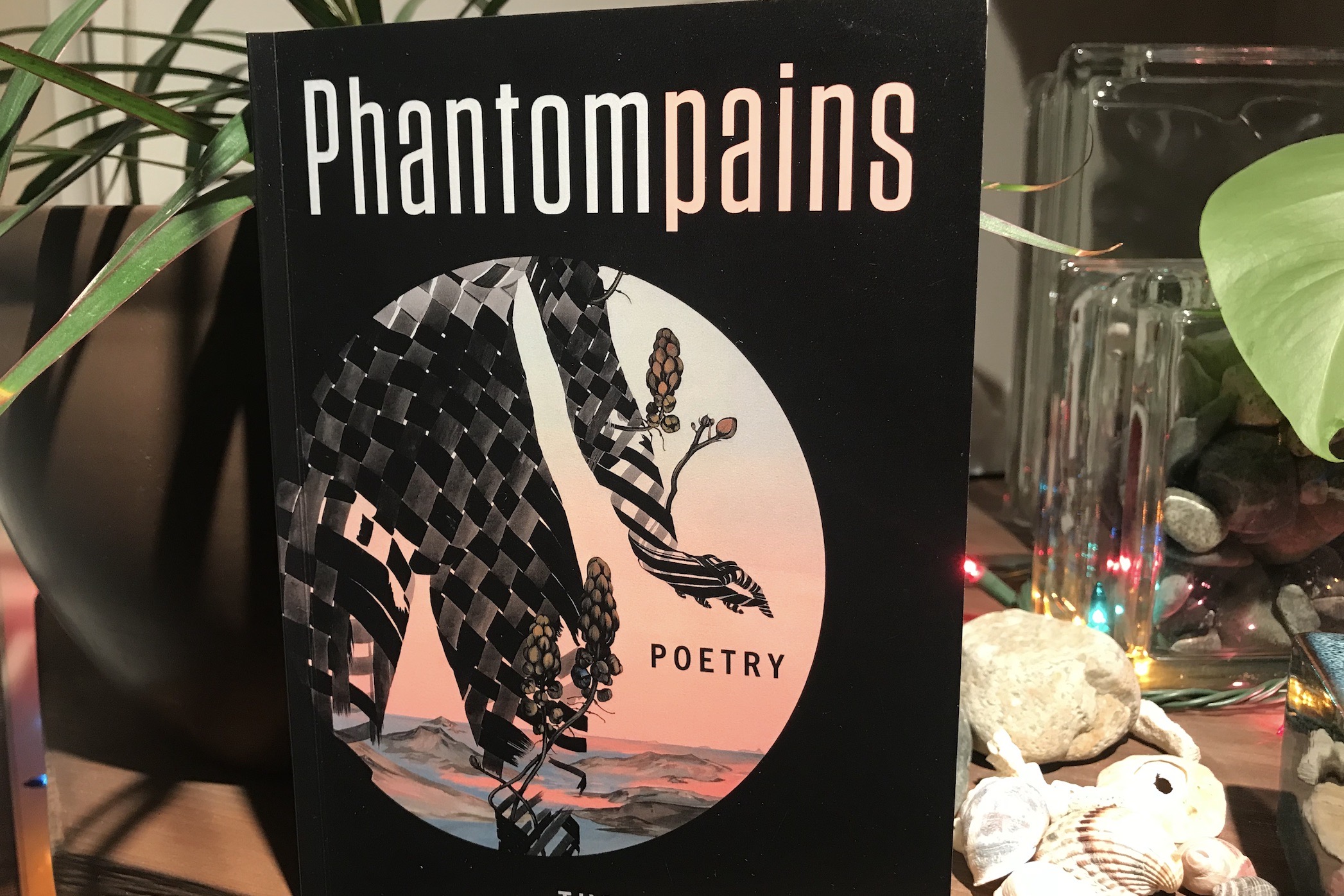

I don’t read a lot of poetry on my own and often feel ill-equipped to comment on it (even as an English teacher), but when I moderated a panel on grief, I was given the opportunity to read an incredible collection by Therese Estacion titled Phantompains. The book both shook and enticed me when I read it, and I want you all to know about it.

Imagine surviving a rare infection that almost kills you, but losing both legs below the knees, your reproductive organs, and several fingers in the process. Imagine spending months in the hospital and then somehow finding a way through such an experience through writing poetry—not only poetry but also poetry that takes its inspiration from Filipino folk and horror tales. Enticed?

Estacion does marvelous work integrating these tales into visceral narratives of her time in the hospital and afterwards. Her poems are haunted by the spectres of “agta” (ogres), “duwende” (gnomes), and “ukoy” (mermen), and also by pain, disability, and grief. But—and this is an important but—the horror of what Estacion faces those days and weeks and months in the hospital are met with and challenged by the rebellious spirit of the speaker and her determination to capture her experiences and memories through the creative process of poetry.

There is so much wrapped up in these poems—layers upon layers of what most of us can only guess would accompany an experience like this. We’re given a glimpse into the almost dreamlike—and nightmarish—landscape of the mind trying to make sense of something so catastrophic while also trying to navigate a medical system that can be traumatic in itself. What images or beings materialize through the cloud of grief, anger, pain, and loss?

In the poem “Aswang,” about a cannibalistic female monster that can dismember her own body, grow fangs and wings, and then—once she has attacked and devoured her prey—reassemble herself, Estacion writes:

I wish I was her

I wish I could put back together my dismembered body

Snapping my bones inside, tucking in my loose muscles and

nerves Folding in my fangs & wings and sulod sa akong

lawas, daghana gyud ug sundang inside my body, thousands

of knives

To align oneself with a monster full of knives who can pull herself apart and put herself back together—we can perhaps understand a tiny portion of the emotions and desires Estacion experienced—the fierce anger, the desire for bodily autonomy.

This collection ended in a place of both burial and resurrection—a goodbye to lost pieces of the speaker, but also a rising up of a new body. A remembering and creation of fullness as a way to move forward.