I didn’t care for Joan Didion when I first read her work. Of course I admired the deftness, the trick of reporting through a very specific lens, but I was put off by her skinny cool girl aesthetic, her penchant for remove, for pinpointing bleakness in chilly sentences. I craved passion and messiness and heart. I was annoyed and a little offended by “Goodbye to All That,” Didion’s famous 1967 essay about leaving NYC, and by the California transplant whose wonder was overtaken by a snobbish ennui in the city I adored. Not long after I read it, in the mid-80’s, I encountered Didion and her husband John Gregory Dunne in an Upper-West-Side elevator on our way to a book party: I learned with smug satisfaction that they had moved back. She was frail and held an unlit cigarette.

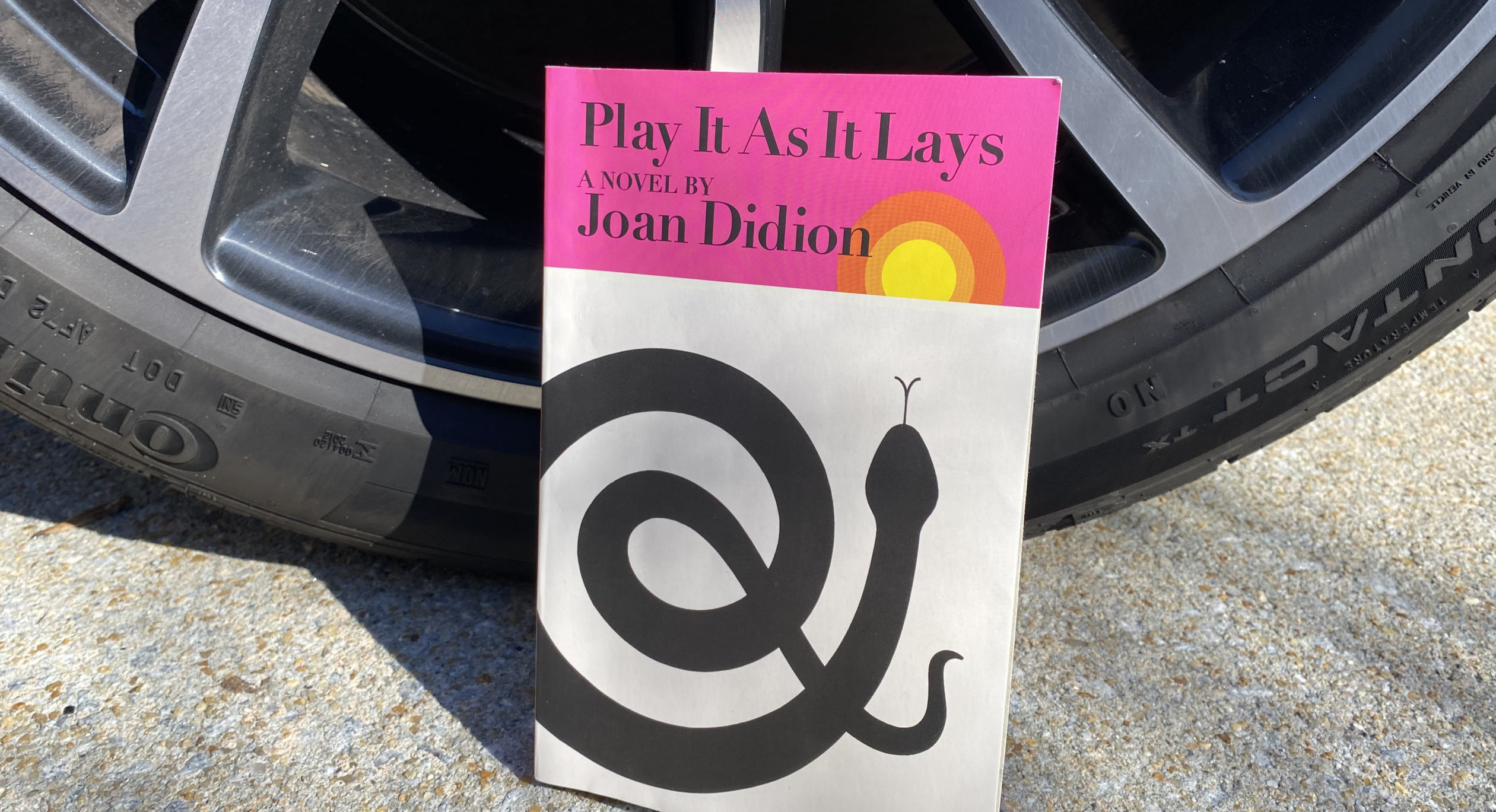

Recently, before Didion died in December, I re-read Play It as It Lays. The short novel, published in 1970, crackles with modern sensibility, eviscerating Hollywood, exposing America’s emptiness, and critiquing women’s lack of power no matter their social standing. I hadn’t remembered that beneath the coolness (of both the beautiful people and the clinical prose) streaks an electrifying current of rage, grief, violence, and despair.

The lovely, dissolving actress Maria Wyeth, in the midst of a failing marriage; a dispiriting affair; an inability to work; a depression that would likely lead to suicide were it not for her young, institutionalized daughter; drives the freeways of LA, aimlessly, recklessly. Born in Nevada, she knows the language of luck, of fate, of playing the hand you are dealt. But in the lurking perils, the cruelty of those closest to her, her paralysis and loneliness, Maria has lost track of the game itself. A harrowing abortion hastens her descent into a kind of anesthetized madness. At one point, she winds up at a stranger’s trailer set in concrete at the edge of town where “the woman picked up a broom and began sweeping the sand into small piles, then edging the piles back to the fence. New sand blew in as she swept.”

We know at the beginning that Maria is telling her story from a psychiatric ward, and we know at the end that despite her pain, she will keep sweeping the sand into piles, dreaming of a safe home for herself and her daughter, attempting to avoid the snakes (real and metaphorical), skimming the guard rails under a pitiless sun, as Didion keeps breaking her heart and ours.