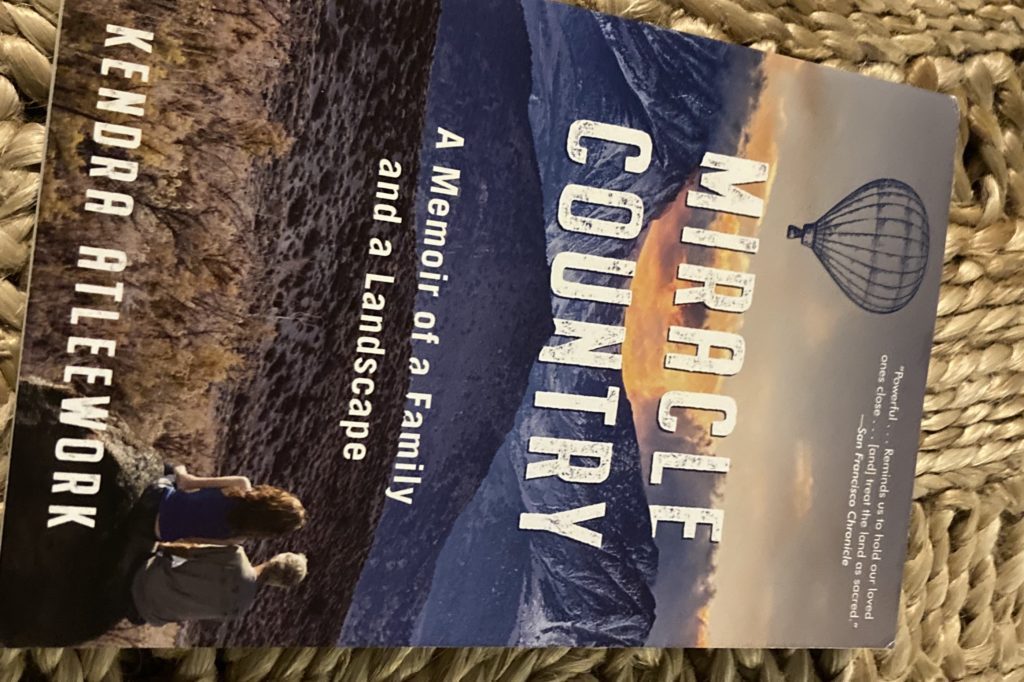

I first saw Kendra Atleework’s memoir Miracle Country in the Lone Pine visitor center, 200 miles north of Los Angeles, below Mount Whitney along Highway 395. The building rose out of the desert to meet us on our seventh summer trip to Mammoth Lakes in ten years.

Each year, I had considered a Mono Lake magnet or a Death Valley T-shirt while my sons and husband pored over a 3D topo map of California’s Eastern Sierra. I had always thought about buying a John Muir book but felt it was too much wilderness for me. I was a tourist, not a climber, eager to arrive at the bakery in Bishop, a couple towns ahead, and then at the lodge in Mammoth with its heated pool.

But this summer, I picked up Miracle Country. Atleework grew up just northwest of Bishop in the tiny Swall Meadows, surrounded by mountains so vast as to feel nearly unmanageable. With her musings about William Mulholland’s century-old aqueduct sluicing water away from the Owens Valley, she echoes other desert soothsayers, Joan Didion or Mary Austin.

Atleework layers memoir with L.A.-adjacent history, comparing her father’s mapmaking and aviation to what many in her valley would call Mulholland’s megalomania: “William Mulholland designed water systems without blueprints or charts. The veins of his city existed as maps only in his mind, and I can’t help but think of my father’s map business, his haphazard, hand-scrawled invoices, his life in the mountains planned around no proven model but some inclination snatched from the belly of a lenticular cloud.”

And so initially, I thought this was an artful book about California history and landscape.

But around page 100, with Part 2 (“Wildflowers”) and Chapter 5 (“Lupine Land”), Miracle Country becomes a book about Atleework’s mother dying when she was 16. And, even though she had mentioned her mom’s death early on, this switch startled me.

I’ve read my share of books about mothers dying since my own passed away eleven years ago, when I was 35. But I tend to know what’s coming when I open them. In Miracle Country, even though Atleework’s descriptions of her mother came unexpectedly, I slid into memories along with her.

She describes the dread at her mother’s illness mixed with the embarrassment of middle adolescence. A shared room at a friend’s house where she pushed away one of her mom’s oldest comforting traditions. Her mom’s longing to know Atleework’s boyfriend two months before her death. A navel piercing done so that her daughter would remember her: “We drove to Bishop because I had begged to get my belly button pierced, and she shocked me by saying yes.”

All of this brought back memories I had not dug into for years. At my older son’s third birthday party, my mom had been sick for two months but would hold off telling me. Cutting through whipped cream frosting on a 90-degree August afternoon, I thought my mom looked old before her time, and I wondered why she didn’t take better care of herself. I just didn’t know.

The book also surfaced lighter memories, more along the lines of church flute duets Atleework remembers playing. Like the time when my mom lay on a battered green acrylic sectional in my parents’ living room, where she lay a lot in the three years she had brain cancer. She put her hands on my head, tilted me toward her, and pulled the two sides of my part in opposite directions. If you’re ever going to color your hair, she said, now’s the time. She never dyed her own silver hair, but I started going a shade blonder that year to cover the early gray she and my grandmother had passed on to me.

And I remembered my mom’s question, six months before she died, once she accepted there would be no more radiation or chemo: Will you be all right without me? She was worried about me, an only child, so emotionally tied to her. She was right to be. While keeping it mostly together on the outside after her death, I flailed inside. I answered so many of my husband’s questions that year with, “But my mom just died!” as a reason not to move forward with buying a house, a car, imagining the next steps in our life with two young sons.

Atleework does, in this book, move forward, but not without significant pain for herself and her father, brother and sister in the decade-plus after her mom died. She chronicles an unforgiving external landscape, along with a churning but ultimately steadier inner one, in ways as luminous and honest as the valley she still calls home.