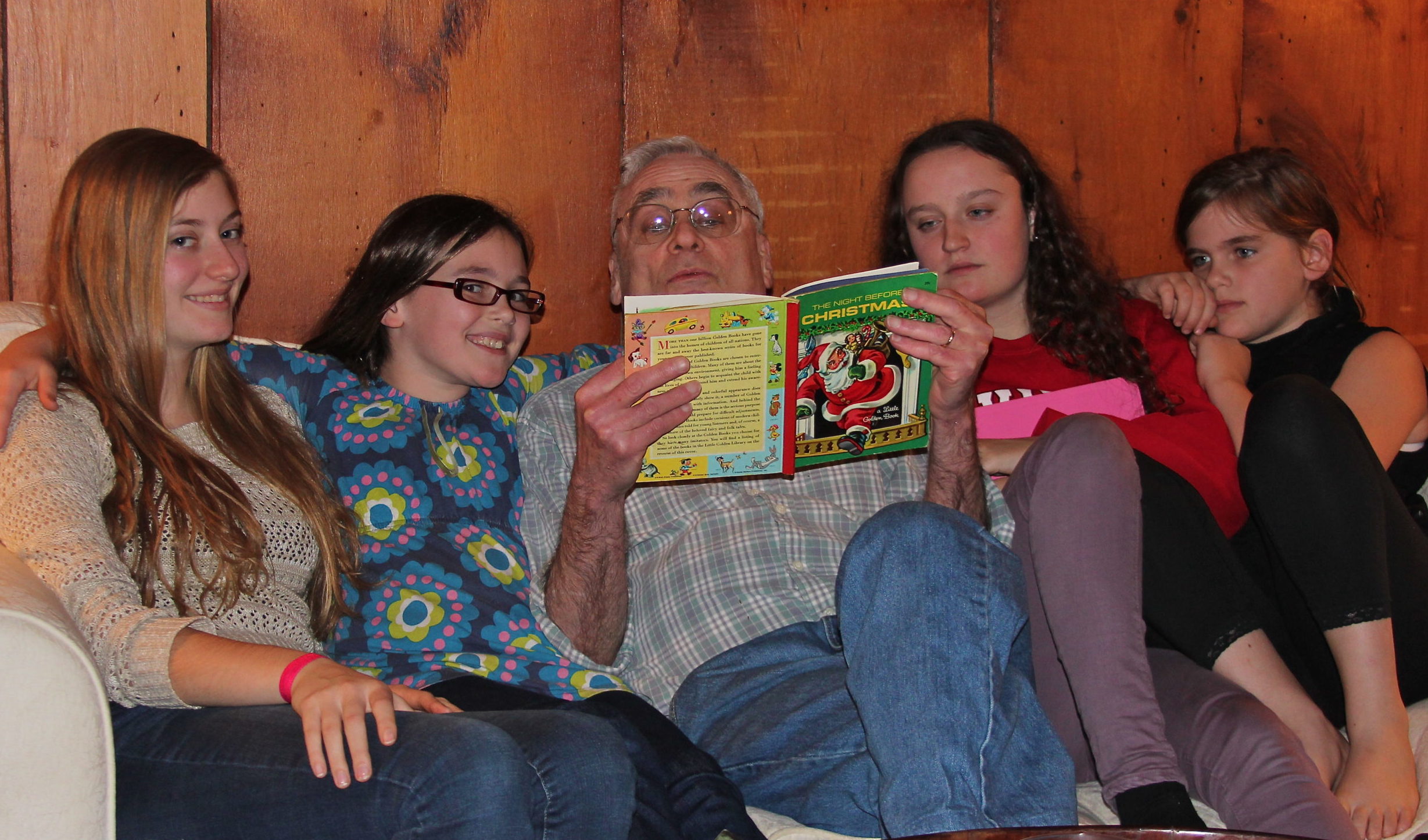

My father, an atheist Jew whose holiday philosophy is basically “bah, humbug,” who barely tolerated our Christmas tree and only slightly more tolerated a menorah, always insisted upon an annual Christmas Eve reading of The Night Before Christmas.* Our Little Golden Book edition, used briefly once a year then tucked away in a drawer with the hand-knit stockings, never lost that new book smell: its clean cover and fresh pages set it apart from the other, well-handled children’s books in my parents’ house. My brothers and I snuggled on the couch, then our children snuggled on the couch (even when they were too old and too cool to snuggle), and my dad relished the chance to perform poetry while his own pipe’s smoke “encircled his head like a wreath.”

This pipe-smoking, poetry declaiming, pediatric hematologist oncologist was and still is a generous Scrooge who nourished my love of literature and, forced into becoming a doctor by his parents, encouraged a vicarious career for me as an English teacher. His den is a dusty, magical space overstuffed with books and the totems of his obsessions: Moby Dick, Scotland, Mozart, The Dallas Cowboys. As a child, I was allowed entrance to listen to poetry: the lilting cadence in Tennyson’s “Song of Hiawatha,” the intensity of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets, the humor of Ogden Nash as recited by my father.

But it was the tradition of reading The Night Before Christmas for as long as I remember that first piqued my fascination with language’s elasticity, its vividness. So many colorful similes! Such active verbs! I was especially drawn to moments of complexity: “As dry leaves before the wild hurricane fly,/When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky” stuck in my brain as I teased out its grammar, its imagery. Old-fashioned words, unfamiliar words I treasured (“droll” “lustre”); the power of naming (fun fact: Donner and Blitzen were originally Dunder and Blixem—Dutch words for thunder and lightning); I adored the detailed liveliness of the “right jolly old elf” himself, for whom we left a plate of Nilla wafers and a tin mug of milk.

As an atheist Jew myself, one who loves our Christmas tree and remembers to light the menorah, I am grateful to my father for his insistence on poetry, on tradition, on reading, and I quote with cheer in these troubling times, “Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good night!”

*”A Visit From St. Nicholas” by Clement Clarke Moore