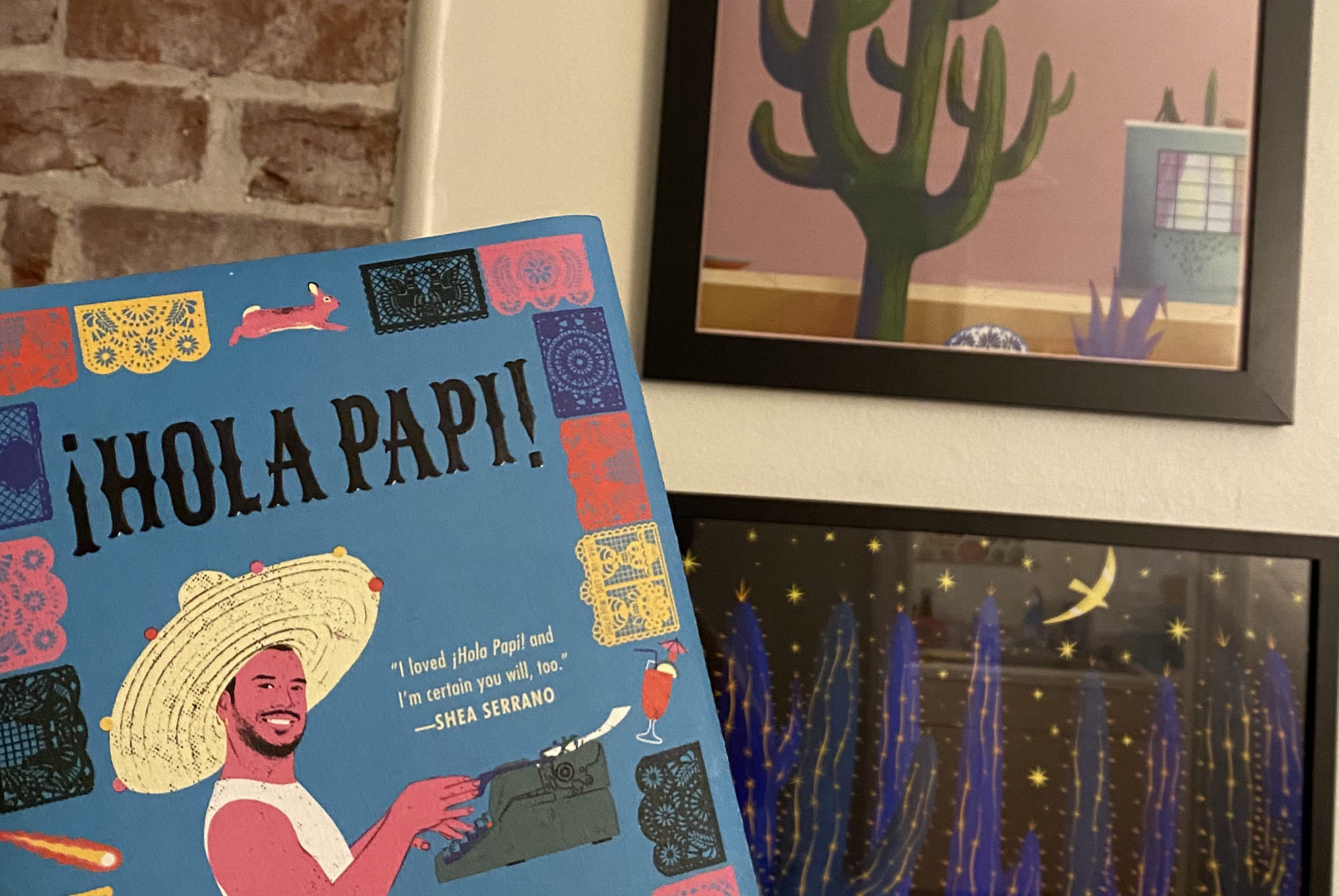

I’m usually the last person to extol the virtues of social media. I’m sure I can even attribute deteriorating mental health to the amount of time I spent on Twitter. Nevertheless, this frequently toxic platform has also brought me closer to people already in my life and connected me to wonderful activists, artists, and thinkers. My friends and I send each other tweets from people we admire or find funny. Especially during the past year’s pandemic, hitting send on a tweet to our group chat was sometimes all the communication I could muster on a given day. Our weirdly accumulated community of Twitter people was a lifeline to the outside world. J.P. Brammer is one of those people we discovered: his frequently hilarious, sometimes inane, always interesting tweets found themselves on our timelines and in our groupchats. We learned he was an artist, and so we bought prints of his paintings for our houses–beautiful, magical, surrealist paintings to brighten up our living rooms as we shuttered ourselves through the winter of 2020. And only after all that did we learn about his main profession: a writer! Brammer was an advice columnist about to publish a book.

First, a bit of context: John Paul Brammer is a queer, Latino writer and artist, originally from small-town Oklahoma and currently based in Brooklyn. He began a slightly satirical advice column originally for the LGBTQ dating app Grindr that eventually moved to the online publishing platform substack. Each chapter of the book is an essay about Brammer’s life, written in the form of an advice column seeking to address a question from a hypothetical reader. The book feels like an intimate conversation and was that much more fun to share with my close friends too.

We all read the same copy of Hola Papi, each time adding our own annotations. I noticed with amusement the previous reactions to the text, shared the jokes, and felt Brammer’s pain. Brammer is uproariously funny. He explains that the title of the book is his reclaiming of the stereotyping and fetishizing he has faced since coming out, and it’s these anecdotes, some hilarious and many heartbreaking, that make reading this book such a delight. He explores mental health and trauma in an approachable way that nudged me to seek help this year when I really needed it. I could see, particularly through the annotations of my friend, how moving (and funny) some of his recollections were about his Latinidad and childhood. We meet his former lovers, bullies, coworkers, and friends, all of whom shape him to be the self-described “promiscuous, Twitter-addled, gay Mexican with chronic anxiety and comorbid mental illnesses who could barely answer his own emails in a timely manner without having a breakdown.”

One of my friends who read this book with me met Brammer recently at a book signing in D.C. He signed Hola Papi to all of us. Brammer’s book, his art, and his Twitter feed have brought us closer together and made the deeply strange parasocial internet culture that will continue to define our lives going forward feel a little less alienating and a lot more fun.