In 1980’s San Francisco, before tech everything, an underachieving college graduate wearing her mother’s old kilt and cardigan could bus on up to the elegant Sea Cliff neighborhood for a day showing filmstrips to the children of the elite. Katherine Delmar Burke school was filled with adorably-uniformed young women whose idea of torturing the sub consisted of Heather pretending to be Kimberly when attendance was taken. The “Burke’s girls” remain in my memory as easy money, harmless preps with miles and millions between them and the grittier neighborhoods down the hill, the “real” San Francisco.

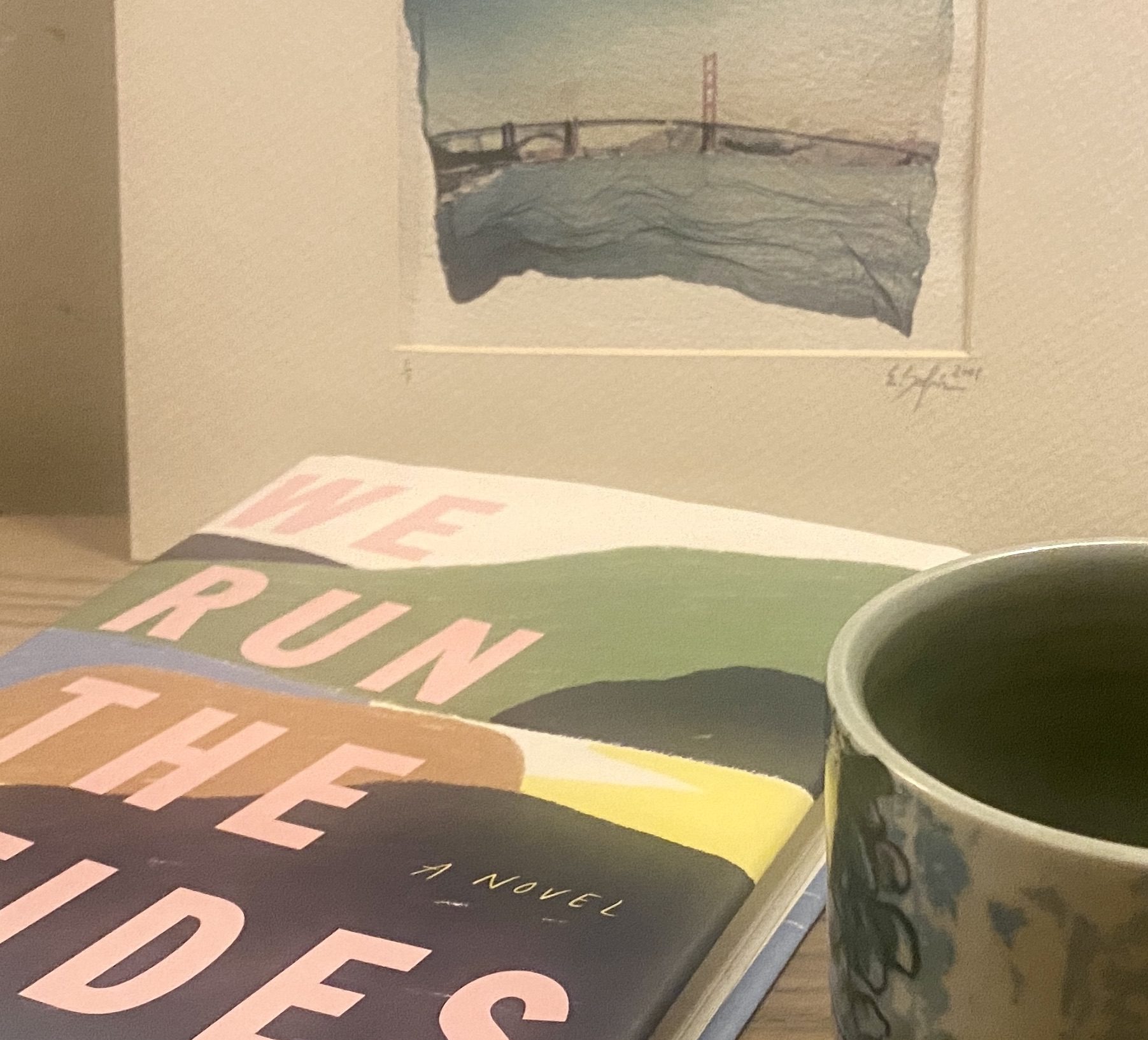

Thanks to Vendela Vida’s We Run The Tides, it seems historical revision is in order. The “Spragg” girls depicted in Vida’s arch, affecting novel are definitely wilder than my memories of their real-life counterparts suggest. Thirteen-year-old narrator Eulabee runs with a gang that feel like they own the streets and cliffs of their picturesque neighborhood. Their unquestioned leader is Maria Fabiola, whose staggering beauty, memorable laugh, and penchant for fabrication sets the wheels of this quirky tale in motion. An act of betrayal soon alienates Eulabee from girls she’s been friends with forever; the novel captures perfectly the way an iced-out girl removes herself from the tribe with nary a protest, embracing the inevitability of exile. Yet Eulabee’s social ostracism is dwarfed by the sudden and dramatic disappearance of Maria Fabiola, sending the Spragg community into an uproar. More disappearances follow, one more calamitous than the others, but the real mystery of the Sea Cliff girls lies in the stories they tell themselves—about their fragile families and friendships, about the price they’re willing to pay just to be seen.

Lest anyone get the impression that We Run the Tides is another White Girl Gone mystery, then, as the Burke girls used to say to subs during attendance time: guess again. The novel’s strange situations are played for laughs as much as for poignancy. Gentle humor is found in the description of Eulabee’s loving, oddball parents: her father is asked his favorite Beatle and responds that he missed that trend. Eulabee is bemused: “Missed that trend, I thought. The Beatles trend.” On Christmas morning, her Swedish mother is delighted that their Spartan holiday traditions allow them to skip brunch and presents “as though the goal of Christmas Day is to go on a walk before anyone else.”

Eulabee, freed from the bonds of life-long friendships, tries on clothes, boys, and misguided adventures at a frantic pace, hoping to claim a fraction of Maria Fabiola’s star power. A brief, modern-day conclusion tacked on to this tale solves one remaining mystery yet lacks the vibrant immediacy of the rest of the novel. This is a minor quibble, however; We Run The Tides, in a voice both confident and dreamlike, nails the daily undertow of adolescence.