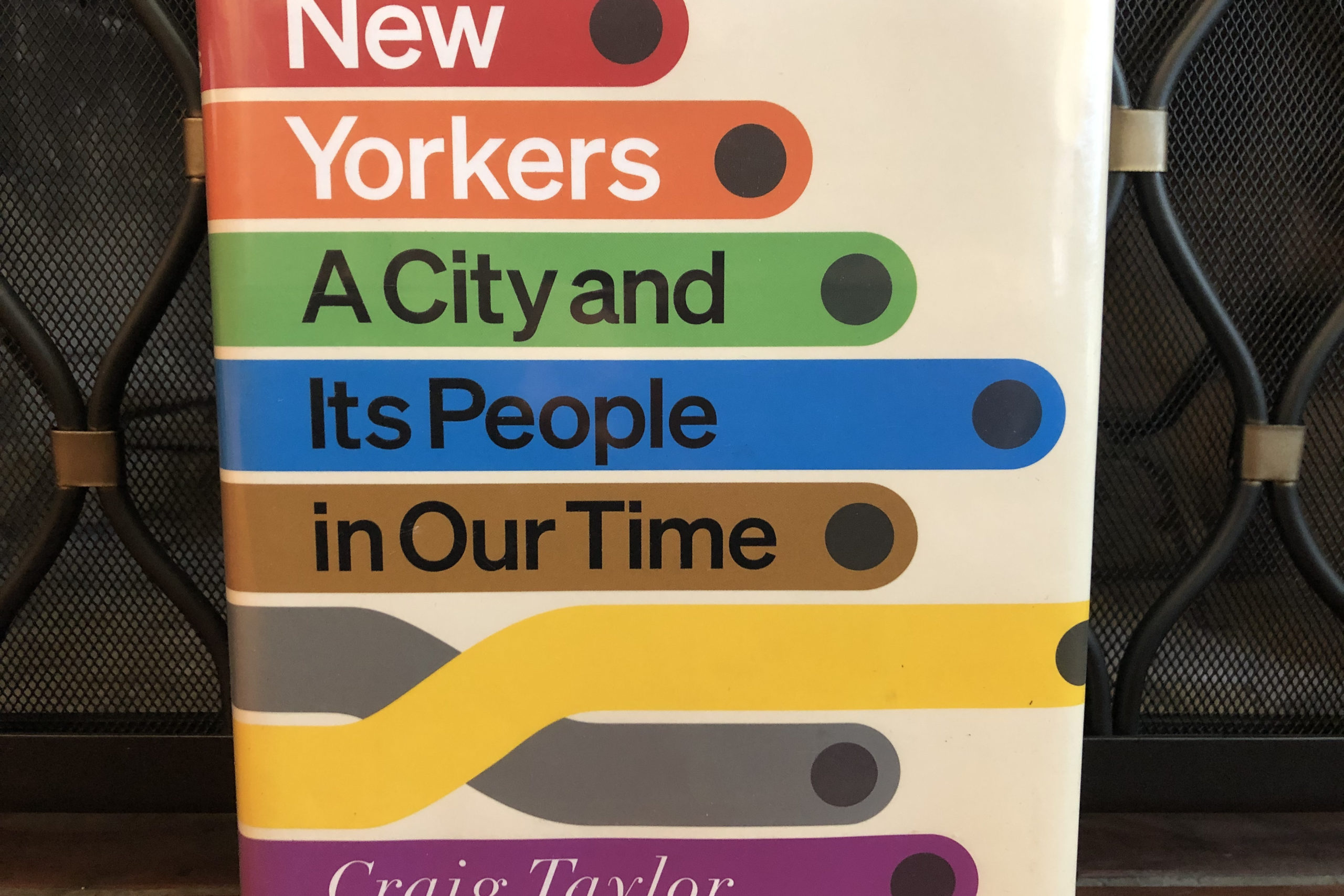

Craig Taylor’s New Yorkers: A City and Its People in Our Time landed in my library stack when the world was starting to open up again, early spring 2021. At the time I wasn’t sure when I would be visiting the city again. But reading this book felt like walking the streets of New York, feeling the collective wistfulness and striving of five boroughs in its pages.

I’m a lifelong Californian who has always loved the city, longed for it. My passion may have begun when I flew to JFK at age seven with my parents, lyrics from Annie tracing through my brain: “N.Y.C./ What is it about you?” This emotional connection has only deepened through visits over the years with my mom, my children, college friends, or by myself.

Before writing the book, Taylor spent a prodigious six years gathering oral histories, interviewing more than 180 city residents and “filling 71 notebooks and just under 400 hours of tape.” As a result, New Yorkers feels like a work of art in how one interview speaks to another – sometimes thematically, sometimes literally if the people know each other. Taylor talks with a window cleaner, activists, a security guard at the Statue of Liberty, a nanny, a sommelier, two anonymous bankers, so many more.

To read this book is to feel alive, to hold in two hands the pride and practicality of a day’s work, to note humanity in an elevator shaft or a doorway to a free meal. As David Freeman, an elevator repairman, muses about his coworkers, “It does end up being like a kind of forgiveness which you develop for people as you know them, which is probably what’s wrong with the world because most people have the homogeneous kind of experience…. But here, in a sense, you’re in a situation where you have a lot of desperate people doing a dangerous goddamn job and, well, after a while you love them. Even if you don’t agree with them.”

The book waxes and wanes philosophical while also landing in your heart in its specificity. I did end up back in New York this summer, on my first plane flight in a year and a half, and two interviews accompanied me unexpectedly.

The first came as I stood on the 102nd floor of the Empire State Building on a stormy night, just as the clouds lifted. I asked a chatty guard where the stairs in the middle of the viewing platform led to, and he said they were for special guests and also for workers on the spire. And then I heard the voice of Jason Nunes, an electrician who had fixed lights on the tower, in my head: “It’s surreal… You go out and there’s a railing this high and you’re looking – open – out off the 104. Then you go up another staircase at the dome. That’s the physical dome and it’s a submarine door that pops open and then you’re physically on the tower. Once you get that wind… Your legs start buckling.” The building became human to me, a place where real people keep those beacons lit.

The second moment came as I stood at the Panorama of the City of New York, which I had not known existed before seeing Fran Leibowitz and Martin Scorsese walk its rivers on Netflix’s Pretend It’s a City. The Lyft ride to the Queens Museum felt like a kind of pilgrimage.

The panorama is a massive scale model, commissioned by controversial builder Robert Moses for the 1964 World’s Fair. As I stood above this mini city, totally alone for 15 minutes in a strange under-touristed July, I watched tiny planes on shimmery wires take off and land from La Guardia. I watched the sun rise and set, saw night fall and dawn come with reddish yellow lights.

And I thought of the book’s interviews with Louise Weinberg, a curator at the museum: “It’s 10,000 square feet, approximately, so it’s the world’s largest architectural model. It is early 1960s design, materials, and engineering. It’s old-school. I mean, it’s gears and string basically.” I remembered her saying it was a deliberate choice to keep the World Trade Center towers intact, “like a willful revisionist history.”

And as I walked out of the museum, past the World’s Fair Unisphere globe, into a newly recreated fog garden that misted my gray T-shirt, I remembered one last observation the curator made: that the panorama “is a repository of dreams.” So is this book – for my New York dreams and everyone else’s.