There is nothing I love more than learning about an author’s source of inspiration: connecting what drew them to a particular theme to the novel itself brings an added vibrancy to the story. In a February 2021 interview with Another Story Bookshop in Toronto, Ontario, Jael Richardson shared the inspiration behind her fictional debut which was an interaction she witnessed on a visit to her father’s hometown where she met a man her age whose father had grown up with her own. She realized that this man’s life could very well have been the way hers had transpired had her father made different choices throughout his life.

As the man reminisced with her father, Richardson wondered, “What happens when you grow up in a world that’s designed for your failure? What choices do you make? What kinds of opportunities are available to you or not available to you? When do you realize that the world is kind of against you?” In Gutter Child Richardson explores these questions alongside issues of race, colonization, and injustice without being bound to the realities of our current world.

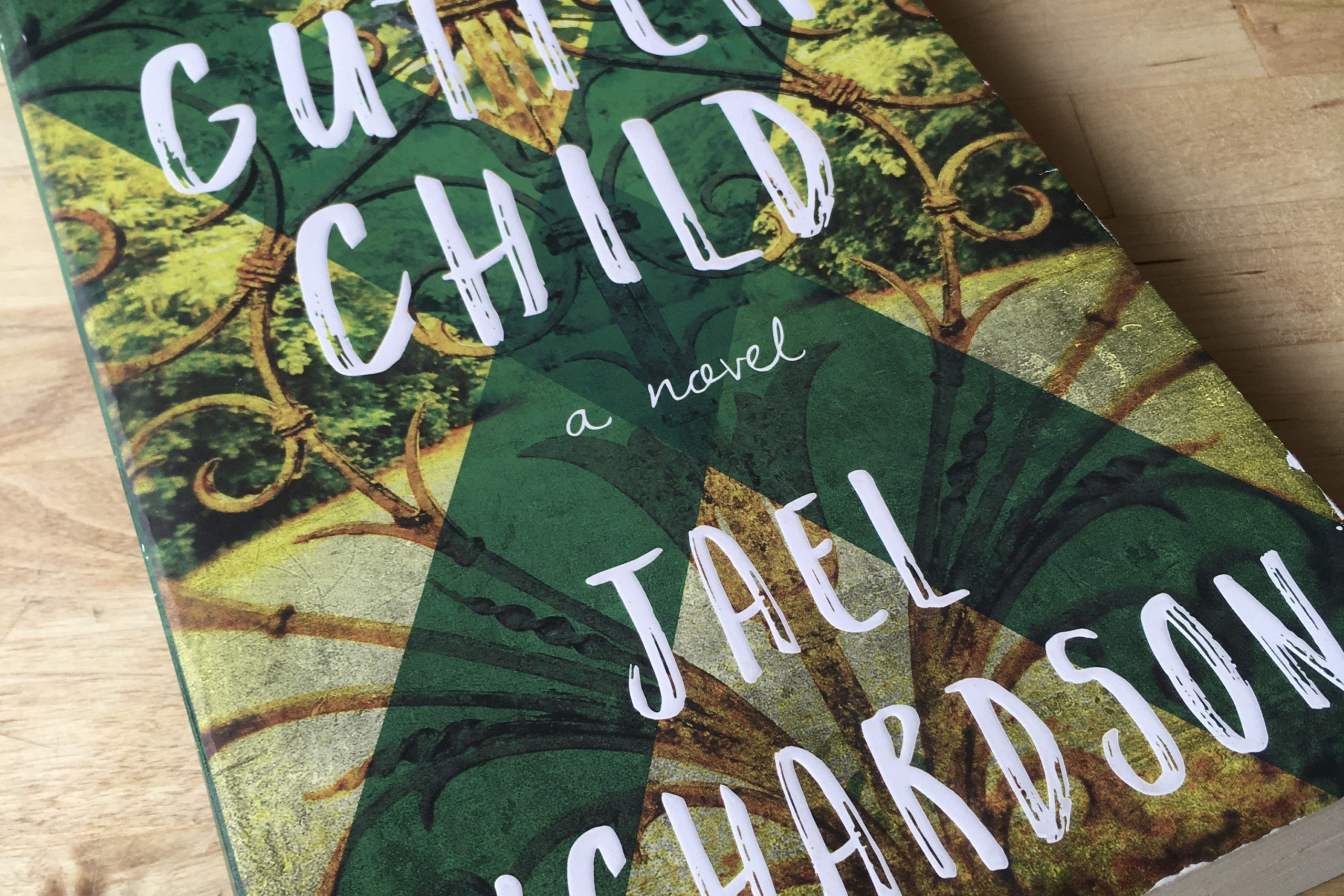

Set in a dystopian, yet all-too-familiar world, the book describes a nation divided into the Mainland, home to the privileged descendants of the first colonizers, and the gated and policed Gutter, inhabited by the Sossi people, original dwellers of the land. In order to pay off their debt to society for daring to fight for their own land, the Sossi people are forced to buy their freedom by working in a society designed for their failure. Elimina Dubois is one of a hundred babies taken from the Gutter at birth to fulfill a special project led by the Mainland government. When her adoptive Mainland mother dies and leaves her without a family, Elimina is taken to Livingstone Academy to begin the path towards paying off her life’s debt. With this abrupt change in circumstances, Elimina finds herself surrounded by children who look just like her, and she begins a journey to belonging and a clearer understanding of her own identity. Needless to say, as I grew up as one of three Black girls in my predominantly white private school of 600 students and as the child of immigrants living on stolen land, and now, as I am the mother of an adopted child, Elimina’s story resonated with me and made me feel seen in many different ways.

As I prepare my year of teaching seventh grade English Language Arts, it’s difficult not to consider representation with every book I read that features diverse characters. I find myself wondering, who is this book for? are their authentic voices being heard? Is someone unrepresentative of them speaking on their behalf? There were many moments throughout my reading of Gutter Child where the similarities to Canada’s Indigenous peoples and residential schools were more prevalent to me than any connections to Black history in North America. While I am conflicted, I do wonder, now more than ever, if highlighting these connections is more important than ensuring that the voice speaking them is accurately represented. Perhaps it’s more important for all those who have been oppressed in recent history to speak up on behalf of each other? As Elimina wonders on more than one occasion, “what if greatness only happens when we’re together, when we don’t let them pull us apart?”

This dialogue-driven novel is a beautiful work of speculative fiction. Because it is situated in an unknown time and place while lacking the supernatural elements often found in this genre, and because the characters are never explicitly labeled according to skin color, Richardson makes it easy for her readers to relate to the world she has built through a critical lens. Through Elimina’s evolution, Richardson implores us to consider a future where those who are oppressed come together to end the cyclical symptoms of colonization. Free from a sugar-coated, happily-ever-after ending, Gutter Child ends with a beginning in mind, with a sense of hope, a determination to see a better world, and most importantly, an air of possibility.