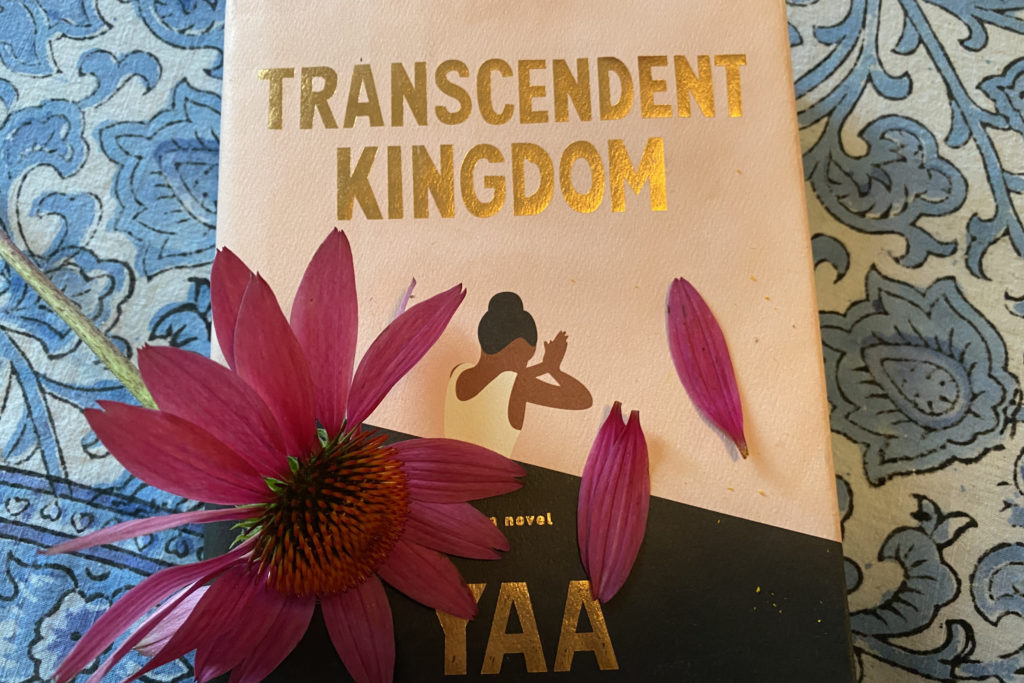

When she was just 26 years old, Yaa Gyasi’s ambitious, decades-and-generations-spanning-debut novel Homegoing garnered critical praise and awards for its exhaustive examination of the vast destructive consequences of slavery in West Africa and America. Gyasi’s new novel, Transcendent Kingdom tightens its attention completely onto a family (first four, then three, then two) of immigrants from Ghana in Alabama. The first-person narrator Gifty is a young PhD candidate at Stanford studying neural mechanisms responsible for risk/reward behavior in mice that could unlock treatment for two diseases that have devastated her family: depression and addiction. Abandoned early on by her father (a man too tall, too Black, too foreign to breathe free in the South); raised in the all-white Pentecostal church by her over-worked, strict mother; in awe of her charismatic, athletically-gifted older brother Nana, Gifty recounts a pious childhood shattered by her brother’s tragic overdose and her mother’s subsequent paralyzing depression. The book opens as Gifty, close to finishing her research and living a lonely, narrowly-focused life in the lab, takes in her mother, come from Alabama to California, who collapses back into bed, hardly moving for the rest of the novel.

Gifty’s voice, that of a scientist—logical, examining, dispassionate—is tempered by entries in her childhood diary written to God that chart her desire to be perfect, her connection to her beloved brother, and her pleas to an increasingly deaf deity. Gifty is not always a likable character, but we can see how heartbreakingly damaged she is, how resiliently hopeful even in the face of burdens heavier than she can bear. The rise and fall of Nana, who becomes addicted to opioids prescribed for a sports injury, illustrates Gyasi’s critique of the role Black immigrant boys are forced to fill, but it is the relationship Gifty has with her mother, unnamed except in diary code as TBM (The Black Mamba), that is central to the book. TBM is unsentimental towards her daughter, but bathes her stricken teenage son; she is forced to spend more time with the white families she cares for than with her children home alone; she disparages therapy in favor of prayers; she embodies the dread of more loss that plagues Gifty as a child and now; she “suffered and she persevered, perhaps in equal measure.”

Even despite, perhaps because of, such a compressed focus, Gyasi’s themes are expansive and profound: what wires us, soul or brain? divinity or chemistry? Gifty the scientist, Gifty the faithful rejects the false dichotomy of religion versus science: “I used to see the world through a God lens, and when that lens clouded, I turned to science. Both became, for me, valuable ways of seeing, but ultimately both have failed to fully satisfy in their aim: to make clear, to make meaning.” The meaning that Gifty searches for in Transcendent Kingdom has to do with alleviating the shame, grief, and fear of her past by balancing the answers of science and the wonder of faith for a more peaceful future.