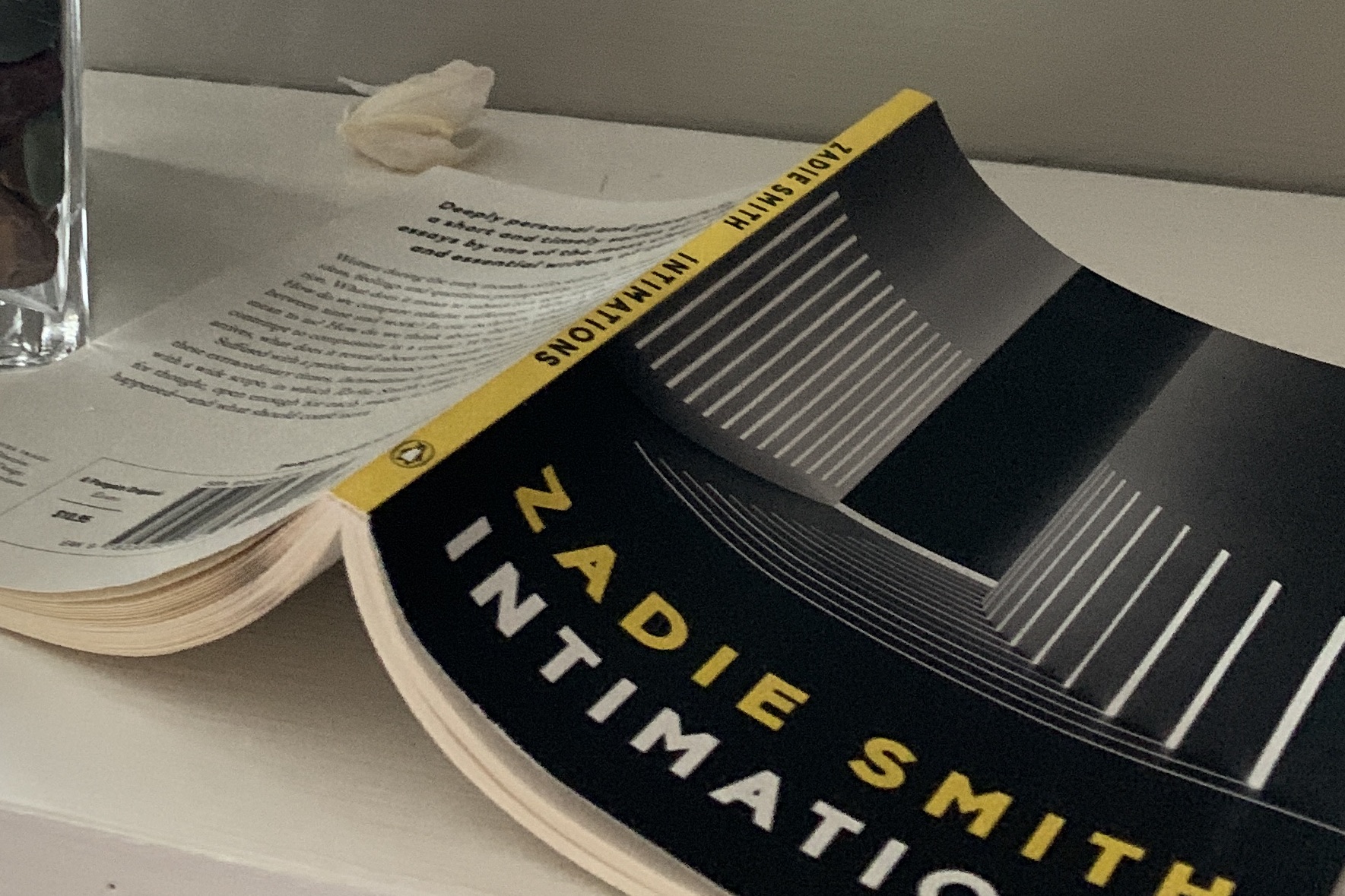

After countless articles and podcasts about our “new reality,” reading Zadie Smith’s brilliant and precise observations in Intimations felt like an exhale to a breath I’d been holding for some time. In these six essays, published one year ago this month, Smith reflects on early pandemic life, death and contempt in America, the writing life, and the personal and absolute nature of suffering. The essays are intimate, wise, and at times startlingly poignant. And like everything else of hers I’ve had the pleasure of reading, they are full of original and crystal-clear thought. At times the experience of reading the essays is like trying on a pair of glasses you didn’t even know you needed: Those far green blurs are suddenly oaks, maples, and you think, Oh, those. Of course.

In her essay, “The American Exception,” Smith explores America’s relationship to death and the healthcare inequities highlighted by the virus. Like so many immigrant observers before her, she names us better than we can ever name ourselves. “Death absolute is the truth of our existence as a whole, of course,” she writes, “but America has rarely been philosophically inclined to consider existence as a whole, preferring instead to attack death as a series of discrete problems. Wars on drugs, cancer, poverty, and so on. Not that there is anything ridiculous about trying to lengthen the distance between the dates on our birth certificates and those on our tombstones: ethical life depends on the meaningfulness of that effort. But perhaps nowhere in the world has this effort—and its relative success—been linked so emphatically to money as it is in America.”

The fourth essay in the book is titled “Screengrabs,” and a few of its sections describe Smith’s interactions with and daydreams of, among others, a Chinese massage therapist, a legless homeless man, and a seventy-year-old chainsmoker. In just a few pages, we come to love these characters through her empathetic and keenly observed details. At the end of each section, though, I found myself gut-punched by the Covid elephant in the room: And now? What are these lives now? In one section, Smith describes a young IT guy, Cy, whose style is “youthful exuberance.” “It should be a season full of possibility,” she concludes the section. “Economic, romantic, technological, political, existential possibility. Yes, among all the various relativities to be considered, age is one that can’t be parsed. The style of Cy—the style of all young people—now radically interrupted.”

If readers are looking for either practical advice or philosophical summations of what all this means, they will be disappointed. Smith provides neither navigation nor hope. Instead, she offers something far more believable, and far more interactive for a reader: portraiture. Here is what she sees—in America, in her neighborhood, in herself—at one moment in time. And this is an intimate 97-page museum I expect that I will frequent, finding new pleasures and wisdom each time. I cannot recommend it highly enough.