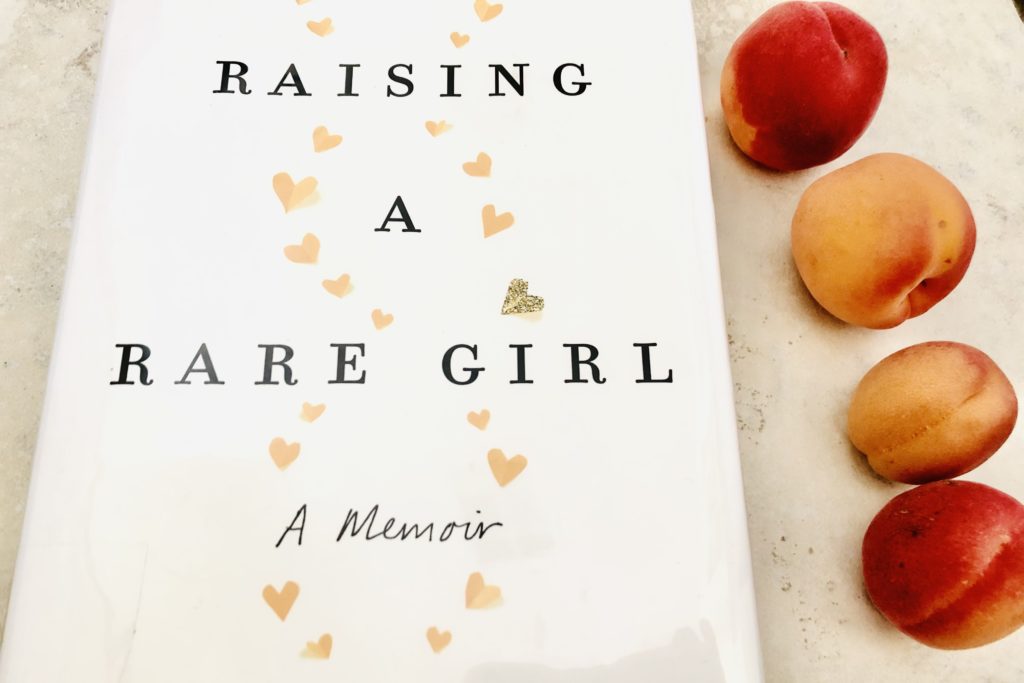

In Raising a Rare Girl: A Memoir, Heather Lanier is so honest and beautiful on the page that writing a review feels like the palest shadow of the book. Describing her daughter Fiona, born with severe developmental delays and diagnosed with the unusual Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, Lanier asks us to envision a different way of looking at people with disabilities: to ask not how we can fix them, but rather how we can rejoice in who they are, as they are.

Throughout Raising a Rare Girl I found myself measuring the quality of my own language, turning a lens on how I react to people with visible disabilities around me, and often coming up short. I’m inclined never to say anything casual about anyone’s children ever again, after Lanier’s observations like this one: “If I’d lived in a world where babies like mine weren’t called bad seeds or measured at zero or denied life-saving surgeries, I know my yearning for an able-bodied child wouldn’t have nagged me quite so badly. If friends had simply said, ‘Oh, severe developmental delays? That’s no problem. She’ll be wonderful just as she is.’”

The book’s heroes are those who embody this attitude. Grateful for effusive speech and occupational therapists, for an empathetic doctor, Lanier describes being “in the company of someone who focuses on your child’s strengths” as producing “a palpable emotional effect in your body. Your face lifts. Your chest feels lighter, more buoyant.”

Part of what makes this story so compelling is that Lanier doesn’t hesitate to turn the lens on herself as well. When imagining with her husband whether Fiona might eventually bag groceries for a living, Lanier discovers “that a chunk of me was snobby and classist and disparaging of grocery baggers. I had to admit this out loud so that I could excise it from myself.” By voicing this, she helps us do the same.

One of my favorite books of all time, and one of the few I’ve reread several times as an adult, is Expecting Adam by Martha Beck, in which the author learns while pregnant that her second child has Down syndrome. She decides to keep the baby, much to the dismay of many around her at Harvard, and the book describes the sometimes unexplainable experiences she has with her son in utero.

Raising a Rare Girl is similar in that it’s told from the viewpoint of a highly educated mother; different in that it focuses not on extraordinary moments but on ordinary compassion. It is also, in the end, a disability manifesto clothed in memoir, considering “disability as a flexible reality, bent and twisted by our notions of the body, and by our assumptions about which bodies are worthy of life.”

Lanier comes to this truth by increments. As she reflects, “There was no single point at which my thinking about Fiona turned away from grief, from the sense of disability as deficit. This happened gradually… When I adored my girl, I took steps away from the fear and the grief.” We as readers walk beside her all along the way.