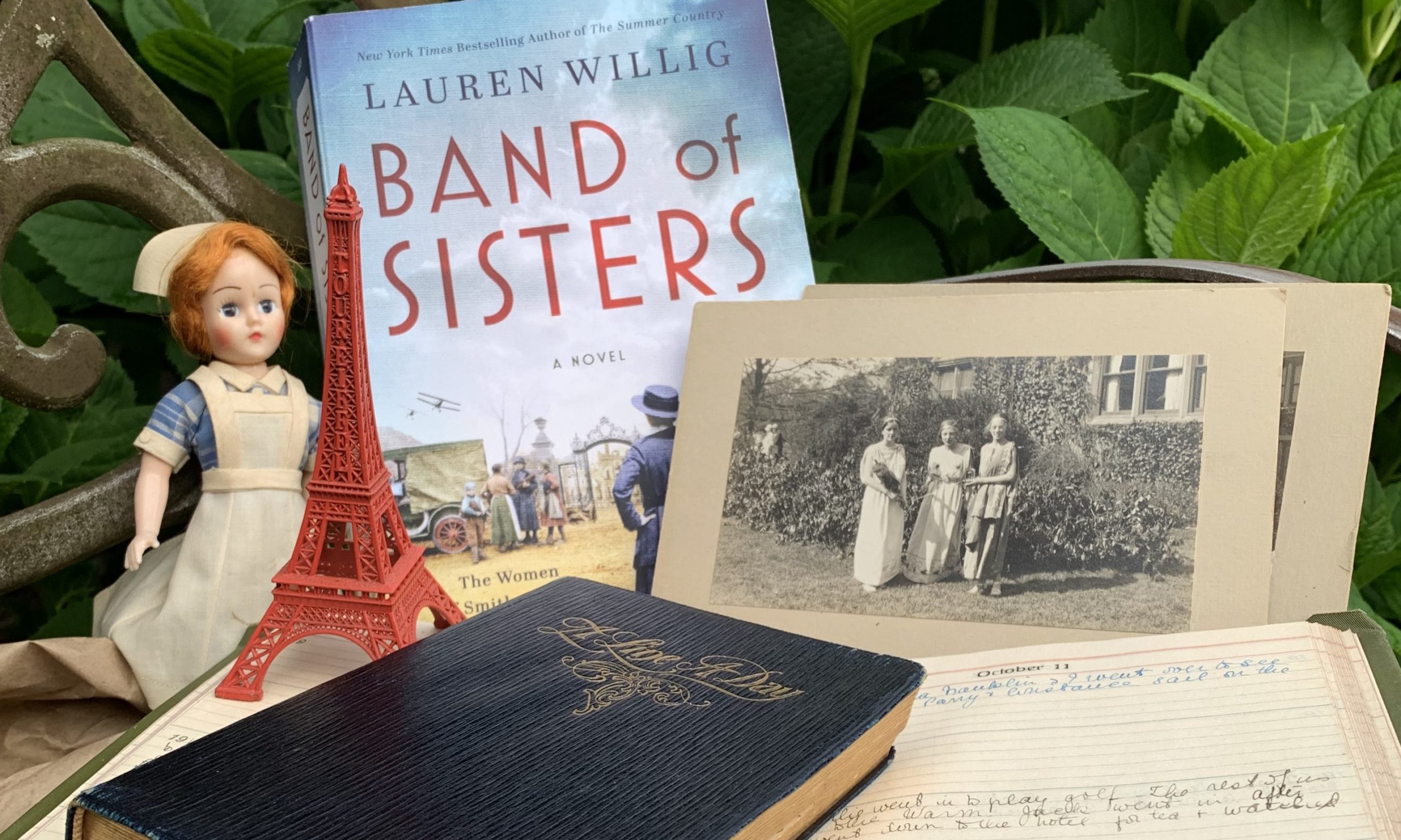

My Great-Aunt Adele, family lore has it, drove an ambulance in France during World War I. Were there letters or journals or anything that could tell me more? No. We know only that she served in France, a secretary for the YMCA in conjunction with the American Red Cross to support the American Expeditionary Forces. A Bryn Mawr College graduate, who shared the family facility for French, she returned home after seven months. She never married and suffered from a palsy by the time I knew her when I was a little girl. She died before I realized the stories she might have told me, had I only known to ask. When Lauren Willig, author of Band of Sisters and a beloved former student, sent me an advance copy of her newest historical novel, I felt as if I finally had context for an unresolved bit of family history.

I was immediately drawn into the story: a group of Smith College alumnae, led by an older alum, travel to France to be of use in the war. Several of the characters are New Yorkers, as is Lauren, so there are wonderful observations threaded through about the Manhattan elite, the social pecking order, the exclusions or snubs. As anyone who has spent time in all girls’ environments knows—and I have spent a total of 37 years teaching in girls’ schools plus 13 years attending one—opportunities for drama are rife when young women live and work together. In my experience, groups of women can be alternately noble and petty, selfless and catty. Even in the midst of war, as they manage preposterous tasks like building a truck from parts delivered in crates and evacuating a village barely ahead of the Germans, the women’s dynamics—their loyalties and friendships, their disappointments and crushes—pulse through the plot.

Kate, whose way is paid for her by wealthy Emmie, is the character whose development interested me the most. She sees the machinations of her society-lady peers with the clarity of an observer, but she is too worried about her own tenuous footing in the group to call them out. A faction succeeds in deposing their leader, Mrs. Rutherford, shortly after they arrive in Grécourt, the little village close to the fighting that they are determined to serve. The mud is a character all by itself as the young women strive to cope with vegetables (the botanist is delayed), set up housing and a school, and provide medical assistance and food for the villagers. Winter is bitter; one girl cracks under pressure; the young women learn to cooperate to try to solve insoluble problems.

Kate’s competence means that she is ultimately appointed to lead the crew, which leads to power struggles with those who do not wish to follow the instructions of someone they perceive as of a lower social class. She struggles with her pride and her sense of obligation, ultimately forging her path, but not in a made-for-television way. That she has been the object of Emmie’s charity rankles her, but she prevails—and Lauren’s understanding of the nuances of class where girls are concerned, even girls from more than a century ago, rings absolutely true. Kate’s resilience and resolve inspired me. But she is no paragon; she is human and, therefore, recognizable.

Lauren’s research is impeccable, drawing on a multitude of letters and documents from the Smith College archives. While some characters are composites and some events were compressed, the portrait she draws of these young women of privilege aghast at the devastation, hunger, and poverty of this region of France is accurate, and she allows her characters to be affected and changed by the circumstances in which they find themselves. Of course, there is a love story, but also the expected bias against women doctors and the sexual harassment—and worse–that these brave pioneering women endured.

Band of Sisters is the perfect read for someone who wants to lose herself in a little-known chapter of another era. Written with deft authority by an author who is knowledgeable about girls and women, it is a gripping story of a moment in time. It was Margaret Mead, herself a graduate of all-women’s Barnard College, who said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” While these Smith graduates may not have changed the world, they were not afraid to take great personal risks and to put the needs of others ahead of their own safety and comfort—they made a difference. I found myself wondering how this experience shaped the real Smithies who inspired the novel. At 60 and 70, did they lie awake remembering the hard things they had done? Did their time in France embolden them to live lives of purpose, to be brave and brilliant women? I have to believe it did. Though I know little of Aunt Adele’s life, beyond the fact that she was a diminutive 5’ tall and had a jolly laugh, I am proud she, too, went to France. I am glad for a glimpse into what her time there might have been like.

The proud teacher in me cannot close without bragging a bit. Long ago, when Lauren Willig was a senior in high school, I advised her very first novel, set in Napoleonic France. Her ambition and command of her craft awed our English Department. An accomplished author, she regularly anchors the New York Times’ Historical Fiction Bestseller list, but even at seventeen, she knew how to tell a story steeped in the details of an era. It’s a privilege to see a student you’ve taught and loved since girlhood become an author of note. How proud I am of the woman she is and how lucky I feel to follow her luminous career!