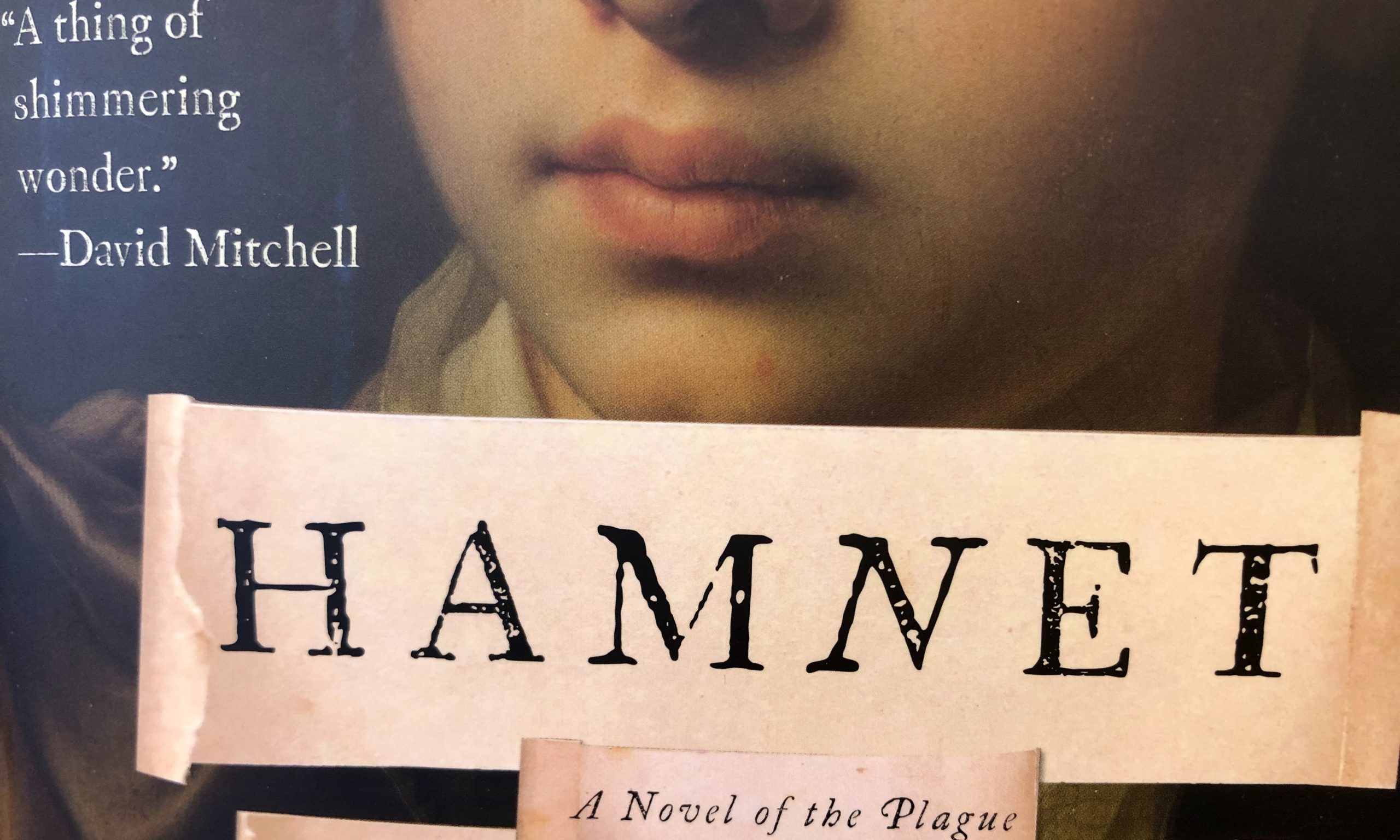

Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet was the first book that I’ve read since last March where I lost myself. There was something exquisite and comforting about the way O’Farrell throws her readers deep into 16th Century England. Perhaps it was the many years I spent reading Shakespeare in school, or the whimsical way she painted her scenes — but whatever it was, I wanted more and more.

The plot alone is a masterful lesson in historical fiction. O’Farrell imagined the missing pieces of William Shakespeare’s life and then went a step further. She told us a story.

The book centers around Shakespeare’s wife, Agnes Hathaway (pronounced An-yes, and thus, an iteration of “Ann”), and the couple’s young son, Hamnet. While the historical record is unclear on the cause of young Hamnet’s death, O’Farrell imagines a plague (plausible yet also apt) and gives the boy a persona, tousled blonde hair, and vibrant dreams. Hamnet’s death becomes the central tension of the novel, and the reader travels on a constant pendulum from past to present, watching the boy live and then die. We also observe how this impacts Agnes and William.

We’ve always known that the play, Hamlet, was inspired by Hamnet, but O’Farrell bravely attempts to envision those threads so we can see the little boy behind the work, the wife and mother behind the playwright, and the circumstances that squeezed such love and pain into Shakespeare’s lines.

While the true details of the Shakespeare family’s lives have remained obscure for centuries, O’Farrell imagines a domestic world for them to inhabit. She constructs a home in her pages for them to live out their daily routines, and lets readers peek through the windows.

We can finally imagine the pulse behind his folios.

In one of her most powerful scenes, a distraught Agnes travels to London to watch a production of Hamlet after realizing her husband had written a play about their son. I’d never even thought about that — what the mother of this little boy felt watching her husband’s play. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to read or watch Hamlet without thinking about O’Farrell’s scene.

Throughout the book, O’Farrell never once mentions Shakespeare by name. He’s always “the young tutor” or “the father far away in London.” We know he’s William Shakespeare, but by not saying his name, we can escape the bard and see the man. By doing this, O’Farrell eliminates the often insurmountable barrier constructed when we try to imagine a world famous genius as a regular person, father, and husband. She doesn’t dwell on his writing — that is secondary to everything at all times.

We know that Shakespeare travels to London, but we see it through Agnes eyes, and through the pain it causes his family. He’s not a famous playwright, crafting some of the most beautiful, poignant lines known to man, but a husband who stumbles, comes up short, and misses saying goodbye to his son.

But perhaps the most wonderful part of the novel was its entrenchment in and commitment to the very best parts of Shakespeare. O’Farrell must be a student of Shakespeare, because in every scene, I saw glimmers of his most glorious pieces. She illuminates the characters, settings, and events that become Shakespeare’s most iconic pieces, and she does so in present tense, as though this, too is a play.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, or As You Like it, or Romeo and Juliet — they were all tucked in there. I glimpsed Puck as Agnes crushed herbs and flitted away into the woods to give birth to their firstborn daughter, Susanna. I felt the passion of a young Romeo weaving through the scenes of Agnes and William’s courtship. I could hear Hamlet’s “a plague on both your houses” as the pestilence takes Hamnet’s life. It wasn’t overt, and it wasn’t obnoxious. The allusions hid in nooks and crannies, between commas and in the adjectives O’Farrell chose.

And it reminded me that it is always real life that inspires the art.