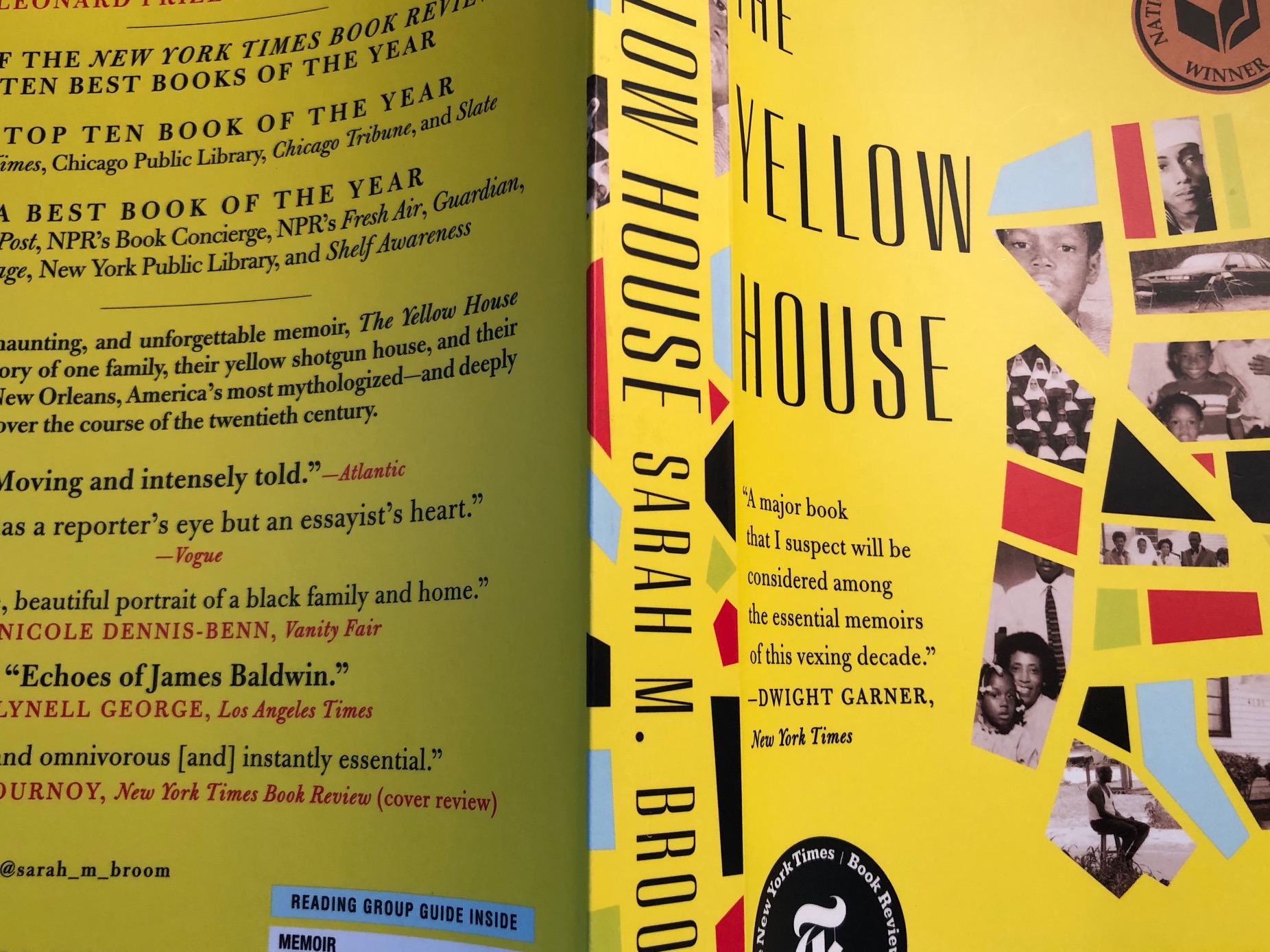

Writes Mary Karr in The Art of Memoir, “Memory is a pinball in a machine – it messily ricochets around between image, idea, fragments of scenes, stories, you’ve heard. Then the machine goes tilt and snaps off.” In Sarah M. Broom’s 2019 National Book Award winning memoir, The Yellow House, the “pinball of memory” is deftly controlled, a counter to the ever-present threat of watery chaos, as well as racial injustice, in New Orleans.

Broom dedicates her memoir to three women – her grandmother, “Lolo,” her aunt Elaine, and her mother, Ivory Mae who had twelve children and raised them at 4121 Wilson Avenue in New Orleans East, the so-called Yellow House. The house was destroyed during The Water of 2005, but its legacy, and the sprawling family that it sheltered, grows larger than life through Broom’s words.

Before it was swept away by Katrina, the Yellow House was the tangible embodiment of Ivory Mae’s unique survival skills. Black, female, and twice a widow, Ivory Mae bolstered herself and her children in the face of a constantly sinking, shifting, too-small home in a neighborhood falsely advertised and inadequately supported as the wealthy and white fled for more solid ground.

Some awful things happened to members of Broom’s family – things that should never happen to anyone, like when her sister, Karen, was hit by a car on Chef Menteur Highway and dragged along, her skin torn from her body. But Broom’s memoir is expansive, showing readers in detail all of the good and happy things that happened in the house that stood witness to it all.

Still, she acknowledges that inviting us to look inside the windows, she is inviting our curiosity, our appreciation, and our judgment. “By bringing you here, to the Yellow House, I have gone against my learnings. You know this house not all that comfortable for other people, my mother was always saying.”

In fact, memoir as a genre is not all that comfortable – for us or for other people. The stories of our lives are not naturally ordered or pleasant. A memoir is about you and the people you knew. It’s about the places you lived and the things you saw. As you are shaping words from memories, you are feeling a host of emotions, some of them surprising, some of them upsetting, many of them a little impossible to beat back so that you can do the work of showing, and not so much telling. All the while, you wonder why anyone would want to read your story. What can a reader you do not know take from your experiences, your photographs, your gains, your losses?

Thankfully, memoir writers such as Broom have the requisite faith that their stories matter and write these remarkably personal works for us to immerse in and learn from.