Last week, on bookclique, the review of Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light reminded me of how much I want a Covid19-free morning or week to dive into the last volume about the life of Thomas Cromwell, arguably tied with Churchill for his place in the imagination of Anglophiles for their reach and influence. Not all of Cromwell’s motives were so pure, and perhaps Churchill’s weren’t either, but of the two, Churchill remains less tainted for me, though Cromwell continues to cast a long shadow.

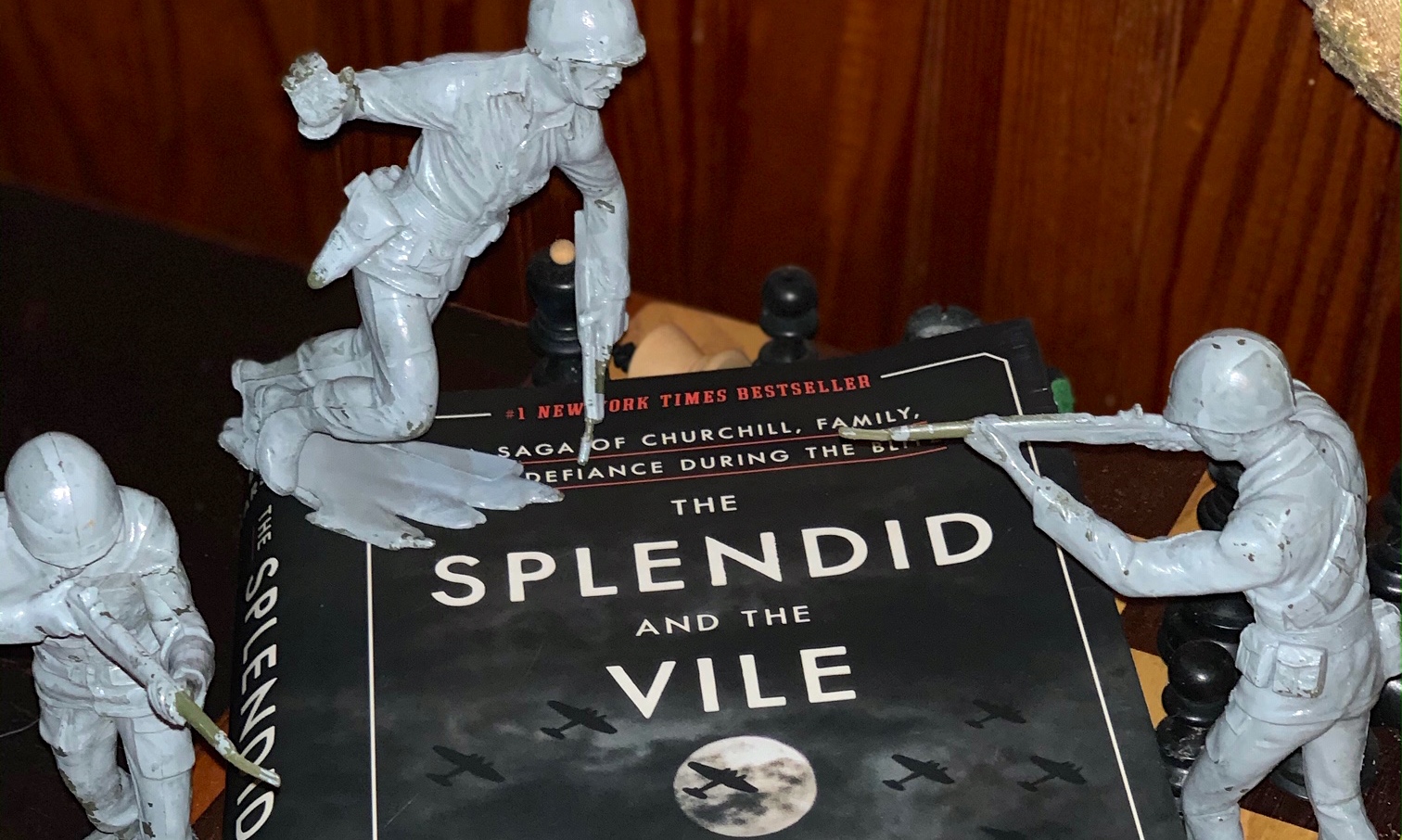

In the week preceding the pandemic, after waiting patiently for several months, I was excited to get the library’s notification that I could finally check out Erik Larson’s newest work, The Splendid and the Vile, from the library. I loved Devil in the White City, Dead Wake, Thunderstruck. As an aspiring writer of non-fiction, I admire Larson’s ability to make historical events read like fiction, and even though I knew that the Lusitania would sink, Larson’s careful control of tension kept me breathless.

Our quarantine began, but I was ready with this new tome. I took the book up to my bedside and dove in. I read for several days. And then I stopped. Churchill was splendid. Hitler was vile. To read about Churchill becoming Prime Minister, climbing back into public favor after the devastating losses at the Dardanelles and Gallipoli in his role as First Lord of the Admiralty to the role of Prime Minister, and to learn, again, all London withstood during the Blitz, was inspirational and was too much for me. His resolve, his work ethic, his determination inspired me, but felt like more than I could manage in the midst of our own national disaster with an enemy far less visible than Hitler.

Larson cuts back and forth between London and Berlin; we know of Hitler’s intention to crush England even as we read of London’s devastation. The focus is much more on Churchill than on Hitler, but when Larson introduces information from the German High Command, the reader realizes how high the stakes were; how doomed England, as an underdog, was; how remarkable Churchill’s leadership was. One vivid scene describes the bombing of a nightclub and the gruesome deaths of the celebrities Larson had evoked in brief, specific portraits. That is one of Larson’s gifts — to make us care about characters we meet only over several pages.

Larson does a formidable job laying out Churchill’s first year in office — his bravado and encouragement of the people of England, his determination to involve Roosevelt in the war. Roosevelt, in case you’ve forgotten, took a long time to be persuaded. The cast of characters is lively.

In particular, I enjoyed the diary entries of several of Churchill’s private secretaries, one of whom was quite eager to join the RAF and chafed against Churchill’s extremely late hours. The PM liked nothing more than a weekend escape to the country estate, Chequers, a huge multi-course meal accompanied by vast quantities of alcohol and post prandial discourse until 2:30 or 3:00 a.m. despite his guests’— mostly work colleagues — fatigue. The story of daughter Pamela’s disastrous engagement and its swift cancellation evoked the era; while London burned, people carried on with love affairs and relationships.

My sense is that Churchill was oblivious to most family drama — his son’s debts and infidelity, his daughter’s romances, his daughter-in-law’s affair with the American ambassador — absorbed as he was in running the country. His wife, Clementine, managed the family and managed Winston’s domestic life make it run as smoothly smoothly as possible. I cannot imagine what it would have been like to be married to Churchill. (As I side note, I also read Lady Clementine by Marie Benedict this spring, a novel about how Clementine managed during and after the war, forging her own path.)

By the end of March, I, who generally read fast and almost always feel obliged to finish any book I start, had to shift my focus to lighter fare: The Sweetness in the Bottom of the Pie, Nothing to See Here, mysteries featuring a middle-aged British detective named Vera. Hitler’s diabolical plans — his cold-blooded determination to control the world — overwhelmed me. His villainy combined with the pandemic felt like too much. I could not persist. Feeling very un-Churchillian, I paused, knowing my weakness would have dismayed the man who led Britain.

Because there were no late fees, by early May, my own equilibrium slightly restored, I picked the book up again, gobbling it to the end. I had not known the story of the German High Command officer, Rodolf Hess’ bizarre flight to Scotland on an alleged peace mission. Nor did I know that Churchill crossed the Atlantic to personally entreat Roosevelt to bring the United States into the war to assist England. I did know that Churchill and Clementine walked often among the most devastated parts of the country to see the horror for themselves and to offer comfort. Those moments touched me; he was, paradoxically, of the people, even as his single minded focus was exclusively, myopically on how to fight the Germans.

I finished the book exhausted by the fact that only one year had passed and the war would continue until 1945. I felt huge admiration for the resilience of the British people. I remain intense fascinated by Churchill, himself — his pale blue jumpsuits, his ability to inspire his country with words that he, himself, wrote, his single-minded obsession with his work. He was maniacal, but, unlike his nemesis, Hitler, his motivation was for good, not for evil. He is splendid and yet, after 503 pages, still elusive.

Churchill was a great leader but a lousy role model for anyone seeking work-like balance; at moments during this spring, I thought he would have felt very much at home during a pandemic. He would have whipped us into shape. We, the whole country, would have been sporting masks immediately, and we would have crowded around our radios to hear his rousing, reassuring speeches that made us believe we would prevail.

If we are ever allowed to travel again, one of my first stops will be Churchill’s bunker in London. I have seen it once, but I did not know as much about Churchill then as I do now. I can see him, giving orders from his bathtub, cigar chomped in his lips, unaware that his nakedness might have slightly embarrassed his young female stenographers. There is something fascinating about someone who cares so little about how he is perceived. He was a leader — bold, undeterred by terrible odds, able to inspire others to share his optimism. He did what he had to do; he was relentless. When it looked as if the under-resources RAF would never prevail against Hitler’s luftwaffe, Churchill refused to lose heart and forced the smartest people in England to think with him about solutions.

After Larson’s book, I am not sated, but even more curious about England’s famous, impassioned, fearless, ferocious leader. What a privilege it would have been to have been led by him.