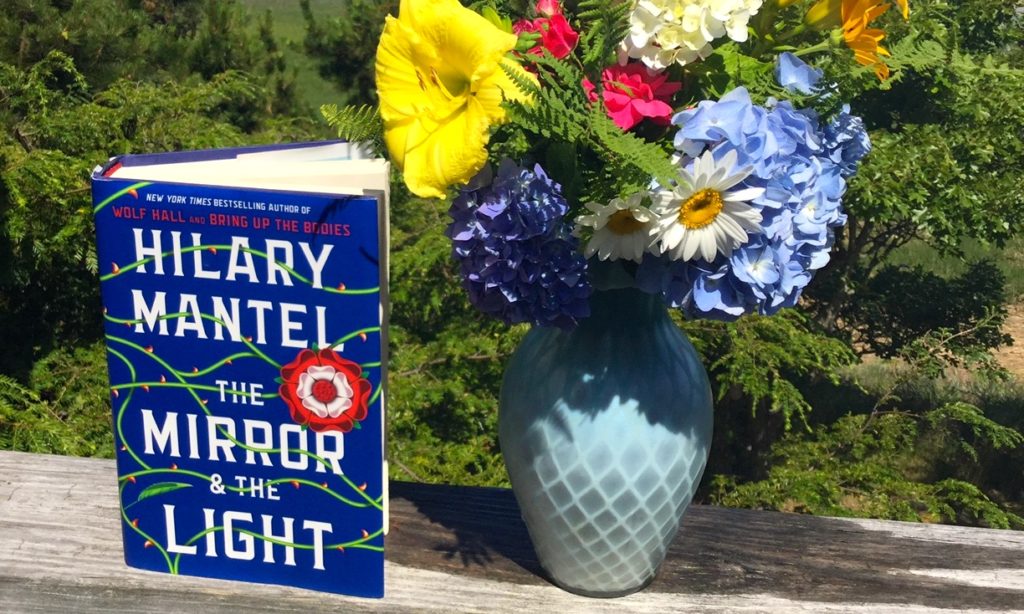

Recently, I was lucky to participate in a great discussion of Hilary Mantel’s The Mirror and the Light. Six of us met remotely several times to discuss each of the books in Mantel’s trilogy — first Wolf Hall, then Bring Up the Bodies, and finally The Mirror and the Light. This third volume completes the story of Thomas Cromwell’s rise and fall as confidant and henchman to King Henry VIII in the court of Renaissance England.

I often have trouble reading straight history, finding it too heavy on facts and data and too light on dramatizing the daily life of the times or helping me to gain a better understanding of its people. History buffs may feel that Mantel distorts the historical record, recreating a well-known set of events from Cromwell’s point of view, but I appreciate the way her reconstruction gives a nuanced, if fictitious, picture of the man. Along the way she brings the sixteenth century so vividly to life with her beautiful prose and imagery that this book is captivating in spite of its 754 pages.

That’s because Mantel is a wonderful writer, underpinning her narrative with sequences of imagery from folklore, the courtly love tradition, the myth of the hero, and other imagery streams. Her descriptions evoke all our senses to imagine how people in the 1530s actually lived and how they experienced life. For example, here are King Henry and Jane Seymour traveling down the Thames:

Imagine England then, its principal city, where swans sail among the river-craft, and its wise children go in velvet; the broad Thames a creeping road on which the royal barge, from palace to palace, carries the king and his bride. Draw back the curtain that protects them from the vulgar gaze, and see her feet in their little brocade slippers set side by side modestly, and her face downturned as she listens to a verse the king is whispering in her ear, “Alas madam for stealing of a kiss…’ See his great hand creep across her person….

Note how easily Mantel shifts from the large perspective on the river to the intimate detail of Jane Seymour’s shoes and feet, signs of her modesty and withdrawn nature. In another passage, we enter Cromwell’s thoughts:

…hear the children learning a motet, and the sound leads him out into the plash of sunlight, under ancient walls. He has seen them in their schoolroom a nest of chirping birds, little bodies huddled together, their voices soaring above their circumstances: when their voices break, who will they be, will they live meanly.…In the song school the notes are painted on the wall so the whole group can learn at once. When they are well learned, the notes are whitewashed over. But none of the songs vanish. They sink deep, receding through the plaster, abiding in the wall.

Through this passage we garner a vivid impression of how children learned to sing in the 1530s, and how Cromwell is able to move quickly from the transitoriness of a moment’s pleasure to an awareness of loss. Sight, sound, and touch merge here into a vivid vignette, animating Cromwell’s walk through the palace.

In the process of telling the story of a man who comes from nothing to be Henry’s right-hand man, enforcer, and advisor, Mantel may stretch history from the point of view of purists, but this did not bother me. Not only did I live imaginatively with her in those remote times, but I thought a lot about the relevance to our own day. Mantel’s historical fiction includes discussions of politics; sex and the treatment of women; religion and intolerance; class, poverty, absolute power; child abuse, superstition, intrigue, betrayal and many other topics that might shed light on our own time. In addition, it’s a rollicking good story. Quoting Petrarch in the final phrase of her trilogy, Mantel takes us brilliantly “into the pure radiance of the past.”