Dystopian societies have a way of fascinating us—of forcing us to recon with the terrible possibilities that lie just below the surface of our own society. In a dystopian world, we are confronted with the horrors we are capable of inflicting upon one another—a kind of introspection that can be necessary and sobering in uncertain times.

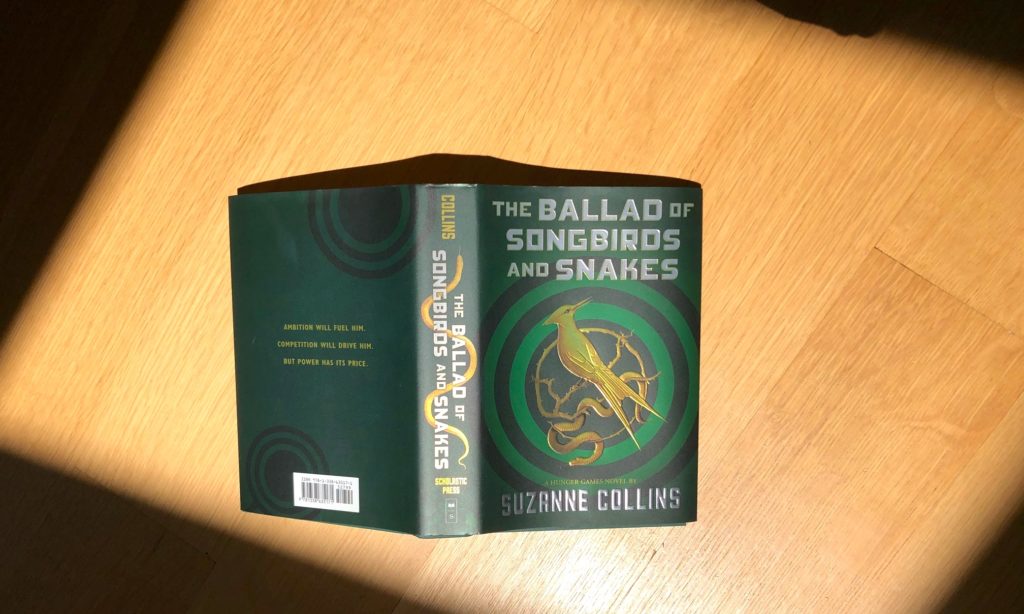

Suzanne Collins, who brought us The Hunger Games trilogy, has now written its prequel: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, the story of the infamous President Snow and his rise to power.

When the book opens, it is the 10th annual Hunger Games, an annual event during which two tributes—a boy and a girl—from each of Panem’s 12 mostly poverty-stricken districts are chosen by a lottery to fight until death in the Hunger Games. Only one of the twenty four tributes can leave victorious. Although the games are televised throughout all of Panem to ensure that hate is stoked between the districts, the game makers in the Capitol are not yet satisfied with the districts’ involvement. Simply put, no one watches the games, thus lessening their impact and their purpose to punish the districts for their past actions against the Capitol.

The solution to greater district engagement? Raising the stakes of the games. Not only are viewers of the Hunger Games now allowed to send in gifts to their favorite tributes, such as water and food, thereby increasing their ability to survive in the arena, but twenty-four Capitol high schoolers will be paired with the tributes as their mentors. The more clout your family has, the more likely you will be paired with a tribute who is from a “strong” district and more likely to win the games.

So when Coriolanus Snow is paired with the girl from District 12, it is the first time he truly realizes that the name Snow has lost meaning in the Capitol since the war, a loss of dignity he has tried for years to hide. He doesn’t tell his peers, for example, that on some days he goes hungry, that he can’t afford to buy new clothes, and that his family is at risk of losing its home.

But in a stroke of luck, his tribute, Lucy Gray Baird, is special. Her charm, and most of all her voice and songs, compel all who see and listen to her. If Coriolanus can earn her trust—make her a favorite among viewers, who, with the new rules, could help her survive—might he have a chance after all? Might he, as the mentor of the potential champion, be able to win the scholarship he so desperately needs to attend university the following year?

But when both mentors and tributes die before the games even begin, and when Coriolanus finds himself entering the 10th Hunger Games arena himself, he beings to question what the Capitol is after. Is anyone really safe? Is anyone really protected?

When I picked up this book, which revolves around a trilogy that is already rooted in our culture, I knew I might be disappointed—I knew that the world Collins created might not live up to the one I was so compelled by before. But, like with her original trilogy, she managed to keep me reading late into the night. Although her writing isn’t lyrically beautiful, Collins has mastered the young adult genre, knowing when to leave her readers guessing and when to give them what they want. She guides us not only through the origins of the games, showing us the beginnings of the brutal arena we come to know in The Hunger Games, but she also helps us forget the President Snow we know from the trilogy. Instead, this is the story of Coriolanus, young man with good, albeit at times selfish, intentions—the story of a man who falls victim to the deadliest and most universal weapons of all: music and love.