Most of the novels I read are young adult, even though I haven’t taught middle school English for years. I sink into them for respite and for hope. These books – unlike the news, unlike most contemporary adult literature – offer redemptive endings. The story is not over, and in fact it’s usually just beginning. And their stock in trade is empathy. After reading a YA novel, it becomes impossible not to remember what it was like to step inside the head of a kid with a learning disability, a kid dealing with gender dysphoria, a kid who has witnessed domestic violence. I feel more open, almost at a biological level.

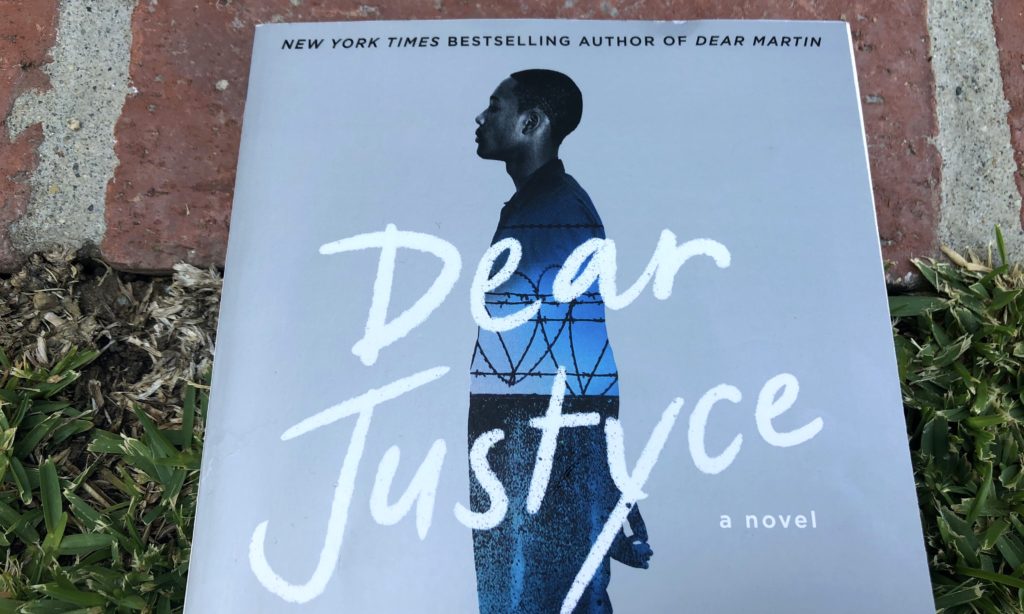

Dear Justyce changed me in this way. It’s the sequel to Dear Martin, which came out three years ago, the same year as Jason Reynolds’ Long Way Down and Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give. All three memorably cover African-American teenagers’ involvement with gangs or interactions with police.

With Dear Martin, an epistolary novel that challenges us to confront racism, the Martin in the title is Martin Luther King, Jr., and the main character is the Ivy League-bound Justyce McAllister. As powerful as this first book was, its companion novel drags us out of any lingering complacency into the life of Quan Banks, who starts off in the same neighborhood as Justyce but walks a far more perilous path.

The novel asks over and over why this happens, why Quan feels powerless at times to improve his life. At one point, Quan writes from jail to his friend: “But what if I can’t ‘reintegrate,’ Justyce? What even do I have TO contribute? It’s not like I haven’t tried to be and do good.” By this point I was wanting to shout to Quan that he has so much to give.

That’s what this novel does. It makes you root for Quan, whose dad was locked away on drug dealing charges when he was eleven, whose small crimes turn into big ones by his mid-teens, whose mentor is an inspirational Black Power-quoting weapons dealer. Dear Justyce makes Quan someone you want to know and understand.

In the author’s note, Stone says, “This is the hardest book I’ve ever written,” especially “knowing the most fictional part is the support” Quan ends up getting from friends and advocates. In order to write it, Stone spent time listening to people’s stories in juvenile detention centers.

The power of story drives this book, even with a detail toward the end as small as Quan’s “seeing two dudes crazy in love – something that was admittedly uncomfortable for Quan at first.” It’s not a key plot point, but Stone slips it in, building in yet another moment of empathy in a novel that everyone should read.