In her book White Fragility, White academic Robin DiAngelo tells White people to get comfortable being uncomfortable. White people, she says, move and live and breathe in a world in which they are all too comfortable never acknowledging the color of their own skin or the privileges that color affords them. So, when discussions of race occur, White people start with other people’s color rather than their own and therefore fail to engage in those discussions from a place of self-knowledge, which many believe is essential for productive “race talk.”

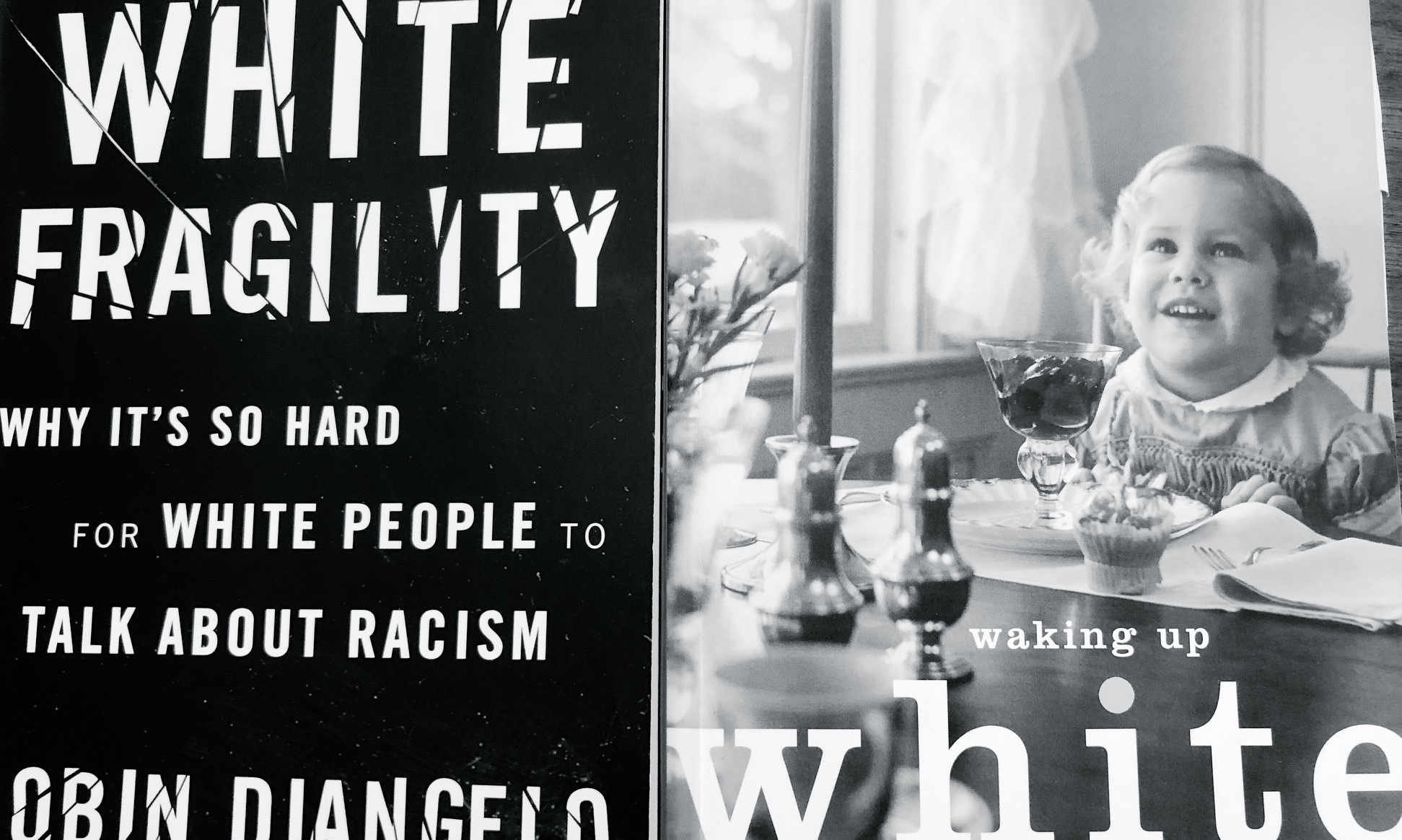

Change requires action, and action requires engagement. White allies scrambling to educate themselves about the ways in which they are White and fragile have pushed White Fragility to Amazon’s bestseller list. I’ve seen it listed countless times on countless Instagram posts as a good “resource for allies.” And it certainly is. I learned more in 30 pages of this book than I did in years of history class.

As the title of her book suggests, DiAngelo suggests that the most fundamental barricade to constructive conversations about race is the overwhelming sense of defensiveness that floods White people when they are confronted with the lived experience of a Black person or asked to confront their own attitudes and actions regarding racial inequality. We White people have grown comfortable in our fragility about our Whiteness and are quick to defend ourselves by insisting that we are not racist and that our words and actions have been misunderstood. This defensiveness, DiAngelo explains, results from a deep belief in a narrow definition of racism as an overt act of discrimination, a definition created and used by White people. When racism is defined this narrowly, it gives White people the opportunity to disengage and distance themselves from conversations, declaring that if they aren’t overtly racist, the problem doesn’t apply to them.

DiAngelo pushes her White readers to realize that this definition is both incorrect and limiting. Until White people let go of defensive feelings and a binary view of what racism entails, we will never be able to confront our underlying beliefs and adjust our blind spots. A racist is not only a White supremacist cloaked in a Confederate flag. It is a liberal school teacher making subconscious assumptions about a Black student. It is a mother telling her child to hush when they point out someone’s darker skin tone. It is a teenager joking around with her friends about being afraid to go to a certain “bad” neighborhood. Like the first step in Alcoholics Anonymous, being anti-racist requires us to admit that all White people — every single one of us — is racist.

“Breathe,” DiAngelo tells readers after she says this, knowing that most White readers will bristle at this statement.

While DiAngelo’s prose is jarringly direct, her conclusions are not actually abrasive. She expertly crafts each chapter around personal anecdotes (“See! I’m a racist, too!” she assures readers); historical, scientific and sociological research; and examples of action steps. Her deft movement within this formula gives White readers many concrete ways to self-reflect and teaches us how to engage in conversations about race that don’t result in defensive responses or tearful denials.

Thus far, most White allyship has consisted of silence on the issues Black Americans contend with on a daily basis. This avoidance is easy for White people because we live in a society that never asks us to consider our privileges before heading to work, school, dinner out, or the drug store. White people don’t have to consider our White bodies in social spaces in order to survive as Black people do, she explains. In addition, we can go through our lives feeling pretty good about ourselves because we do not engage in overtly racist acts or conversations. When we don’t engage in conversations about race, it isn’t because we are racist, we tell ourselves, but because we aren’t.

Much like acquiring a new language and mindset, learning to be anti-racist — to be a White person who is capable of discussing and confronting their own racism — does not happen over the course of a day or one diversity seminar. It is, DiAngelo emphasizes, a lifelong study, and fluency comes from years and years of practice. For White people who want to make progress, it’s an education filled with mistakes, misconjugated verbs, confused sentences, and slip-ups. DiAngelo’s goal is to give White readers the language and various social conjugations necessary to begin to more directly engage in anti-racist work. The work starts with us — White Americans have an imperative to learn about our own privilege and our role in perpetuating the systemic racism we oppose.