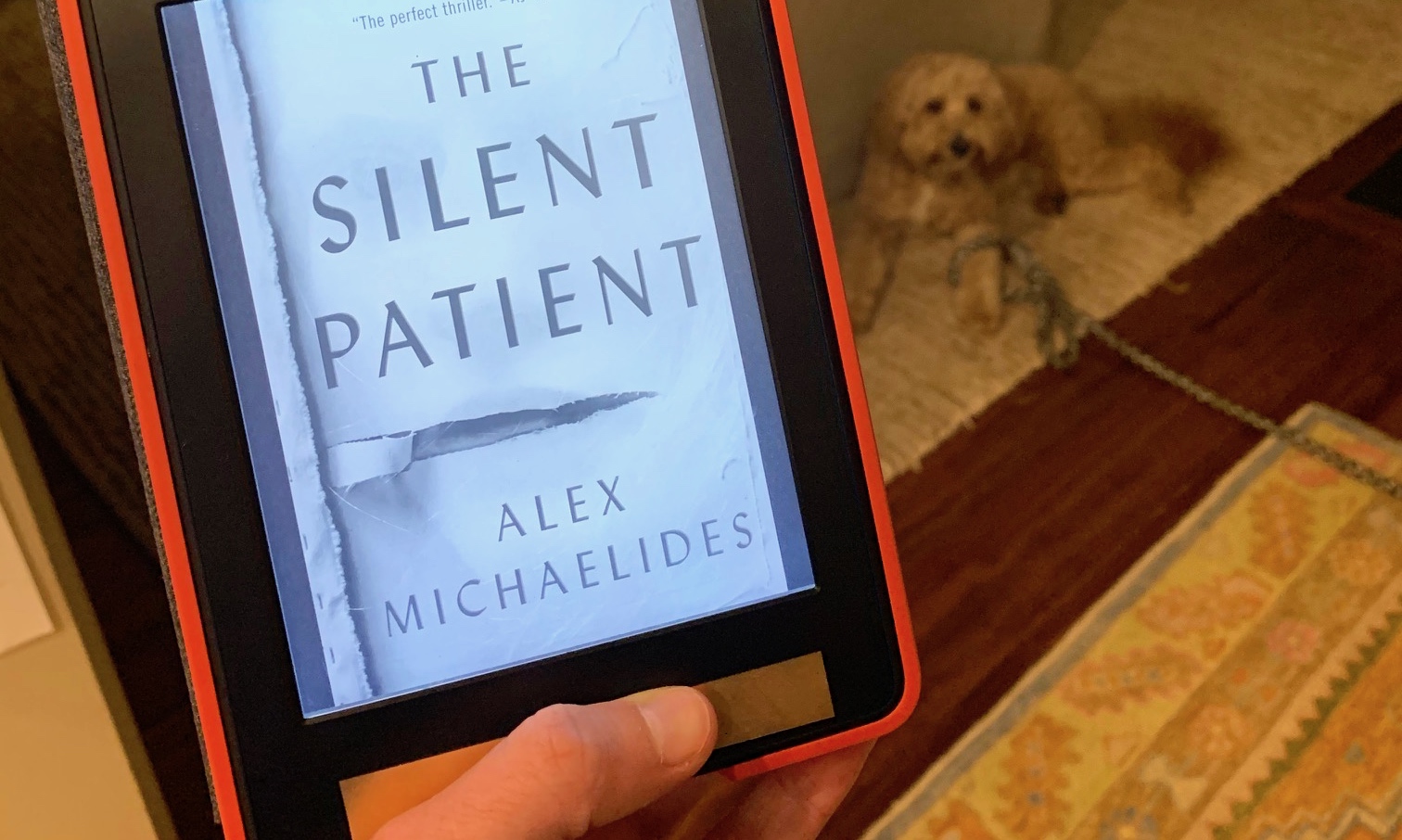

The Silent Patient by Alex Michaelides recently became part of my nightly meditation, my attempt to quiet the news of masks and illness. Instead of scrolling or texting, I found myself falling into this story where people ride buses and strangers touch. Yet, the story also conveyed some deeply unsettling messages – messages that I found even more interesting than the plot’s own shocking resolution.

Michaelides borrows from the always captivating wife-as-killer plot while upending the theme completely. As psychotherapist Theo Faber tries to help mute patient (and supposed “husband killer”) Alicia Berenson speak again, what we actually see are two love stories in parallel – that of Alicia and her dead husband, and Theo and his wife, Kathy. These two love stories are the genesis and terminus of every issue that arises. So, even as we are driven to learn the resolution to the mystery, the novel isn’t really about that at all.

In fact, Michaelides spends most of his time bringing us deep into her characters’ psyches, analyzing their relationships and the impact they have on their lives and identities. We don’t just see that Alicia Berenson loves her husband – we see that she worships him as a god, building her entire life around him and driving her work as an artist. We aren’t just told that Theo Faber has a wife – we see her quirks and know the way she moves through Theo’s world. Theo comes to understand Alicia and her trauma by following her family members and loved ones around and asking questions about their experiences with her.

For a novel built almost entirely on the premise of psychoanalysis and the internal machinations of human beings, we spend very little time alone with the characters. In fact, I would argue, we spend almost none at all. In essence, the characters in this book seem to exist solely through their relationships; they’re shaped by their friends and family in a way that makes personhood outside of their relations impossible. When Alicia and Theo are not remembering a traumatizing interaction with a parent, they’re reliving the first time they met their spouse at a bar, or describing an intimate interaction at home. Their movements are motivated not by self-interest, but by a ripple-down effect from an interaction with someone else. Theo and Alicia lose themselves in their relationships – the good and the toxic. And the impact is devastating.

It was hard to escape this unsettling reality the novel highlighted. So many of us are, in fact, shaped by our existing and past relationships, romantic, familial and friendly. Especially right now. Creating new relationships is not really possible at the moment (it’s certainly not easy to feel real connection over a screen or with a mask on six feet away). So, in many ways, people are stuck reliving pre-quarantine memories, relationships, and feelings. Some feel heavier, more complicated than usual. And most of these relationships are quagmired in an unstable Zoom connection. In a way, it feels like these connections have more power over our sense of self, perhaps because we have nothing distracting us.

As social creatures, we will always rely on our connections to others to give us some sense of identity. Those relational markers show us where we are in the world. But this book reminded me that we can’t be defined solely by specific relationships, as Alicia and Theo allowed themselves to be, because they change and shift over time. Yet, without regular social lives, we spend very little time developing new ways to define ourselves. Maintaining sanity requires defining identity from within, not without. Sure, relationships can shape us, but they shouldn’t control us. Perhaps Alicia and Theo would have met happier endings if they’d realized this.