In light of recent conversations around this novel and its film adaptation, I want to share a few additional thoughts before my original review. Gone with the Wind is an engrossing survival narrative, and it was in that spirit that I recommended it be read this year. Now, when Me and White Supremacy, How to Be an Antiracist and similar such texts are flying out of Amazon warehouses, it still strikes me as an important read this year. Only history will show us through laws and policies how white supremacy gained footing in America. And only courageous self-examination will show Americans how it still maintains that footing in their hearts. But examining art and cultural phenomena, such as Gone with the Wind, has its benefits, too. While the novel’s blatant racism may prove too much of a turn-off for some readers, I encourage those who have the stomach for it to push through. Read it to understand the seductive nostalgia of the antebellum plantation. Read it to understand the devastating impact of slavery on all those who lived through it. Read it to understand why some want Mitchell’s work cancelled. Read it with both the contexts of 1930 and 2020 in mind. It may just strengthen your resolve and––equally important––the tools we’ll all need to make this country more just and equitable.

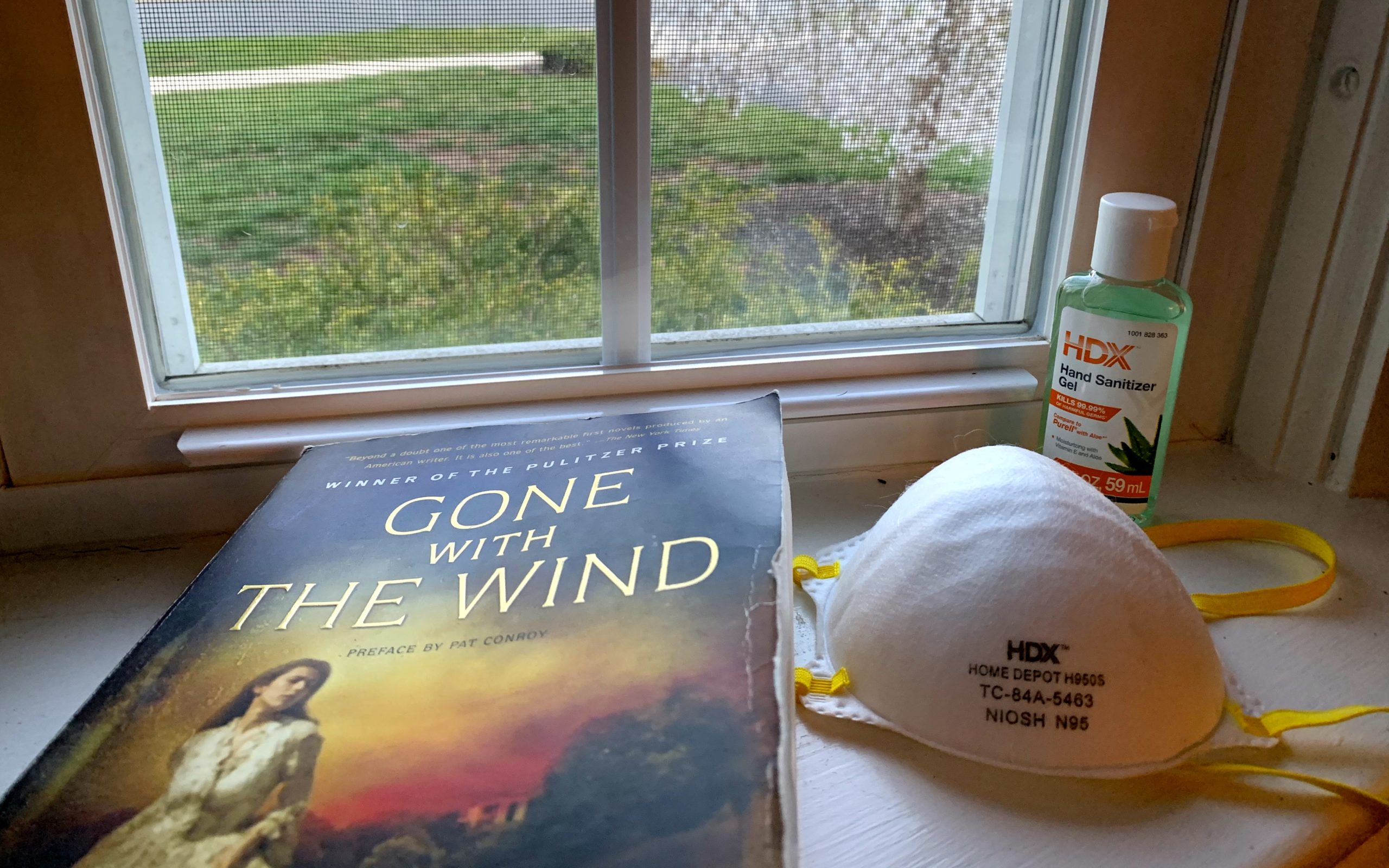

When I began rereading Gone with the Wind in January, I had no idea that Margaret Mitchell’s world of turbulence and survival would become so shockingly parallel to our own by the time I finished in March. The saga begins in Georgia on the cusp of Civil War, when Scarlett O’Hara is 16 years-old. By the conclusion, nearly 1000 pages later, we’ve been whirled through lavish parties, marriages, childbirths, murders, overcrowded hospitals, battlefields, jail cells, brothels, drunken brawls, and one of the greatest love stories ever told. Mitchell makes us captivated witnesses to both the catastrophes of a civil war, and the gumption of those who survive it.

Before I go any further, and at the risk of dismissing them too quickly, I want to be clear that, yes, the novel contains both painful moments of racism and glorifications of an antebellum South. Importantly, though, Mitchell’s failures shed light on similar failures today: lack of recognition that there’s a problem to begin with and the prevalence of American myths of innocence and the glory of yesteryear.

Despite its flaws, I can think of no other American novel whose cast of characters is as fascinating, deep-benched, or memorable. And many of them resonate acutely in this moment. There’s Rhett Butler, who stores thousands of pounds of cotton in London until the need becomes so great, he can name his price, raking in millions. He tells Scarlett there are only two ways to make real money – in the rise and in the fall of a nation. There’s Grandma Fontaine, who explains what makes some people survivors: We aren’t a stiff-necked tribe. We’re mighty limber when a hard wind’s blowing, because we know it pays to be limber. When trouble comes we bow to the inevitable without any mouthing, and we work and we smile and we bide our time. When I imagine too much – those what-if horrors of my husband in an overcrowded ICU, my young children without enough to eat – I quickly force myself, like Scarlett often does, to dismiss the images: I can’t think about that right now. If I do, I’ll go crazy. I’ll think about that tomorrow.

Mitchell’s prose is both muscular and crystalline, and when you enter her world, you enter it wholly. Night after night I found myself staying up too late, savoring just a few more pages and hushing the small voice inside of me that kept insisting: Go to sleep! Keep your immunity up! Night after night I gleefully allowed myself to be transported by a decidedly unlikeable, but completely enthralling feminist heroine. It isn’t just that Scarlett O’Hara refuses to be controlled by men or dictated to by social convention, or that she ends up running Atlanta’s most successful lumber business in the middle of Reconstruction: It’s Scarlett’s instinct for survival, despite her profound naivete and lack self-awareness. Before the War, she knew only comfort and plenty, but she keeps moving through pain, hunger, disappointment, and dread. She braces, in the middle of the unknown, digs her claws in and fights. She does whatever it takes to keep her home and her people safe.

Read or reread it, but read it this year. As Pat Conroy says in his preface from 1996: Gone with the Wind is a book with many flaws, but it cannot, even now, be easily put down. The book still glows and quivers with life. And we need glowing, quivering-with-life art now, don’t we? We need tales of tumult and survival. We need flawed heroes and heroines, who remind us that things may never be the same again, but that’s ok, and maybe it’s more than ok, because, maybe all these deep stresses, borne by a country already in civil unrest, will force us to learn better self-sufficiency, better awareness of others, and better ways to live.