When the world shifted a little over a week ago, the governor of Ohio required we close our school. I didn’t worry; we were headed into spring break. We could manage a few days of distance learning until school resumed. Spring break is the traditional time of year for me to hunker down with books, to read for long periods of time, wake up early to read in bed and stay up late because I couldn’t wait until morning to finish a novel. Coronavirus or not, everything would be fine, I consoled myself.

There are moments that increase our aperture of understanding; small signals that what we thought was going to happen is not what is, in fact, happening. There are certain communications that confirm the world is off its axis. For my teenage son, it was the cancellation of NBA games. For me, it was the email telling me that the library would close. Admittedly, I read with some relief that late fines would be forgiven and we could have the books already in our possession for as long as we liked; I had just checked out Erik Larson’s The Splendid and the Vile and was looking forward to devouring it over spring break.

In the past week, I have opened — and shut — this splendid book many times. I love the way Erik Larson tells a story, as if we are right there in 10 Downing Street in the early days of WWII. I admire Churchill, his bravado and spirit in leading England. I laugh at the idea of his giving dictation to his many typists from the bathtub, his confidence. I can practically smell his cigars and see his advisors: Pug Ismay, Lord Beaverbrook, his long-suffering wife, Clementine. As I wrote to families in my school this week, I tried to summon Churchill’s talent for rallying the citizenry, for persuading people that they could manage through whatever needed to be managed through. I am no Churchill, surely, but I was grateful for his words, his courage.

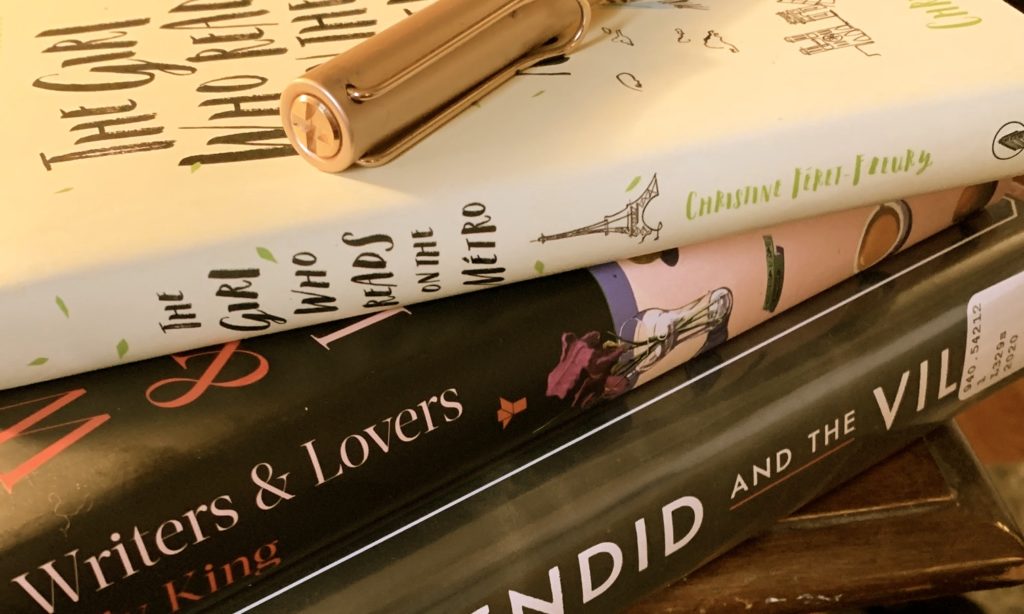

And yet, I have not been reading for hours and hours, but in small sips. In trying to make sense of our pandemic and Britain’s travails, I can only manage a few pages at a time. I am surrounded by books to read over these next weeks and months while life, as I once knew it, is on pause. My dear friend, Myrna, sent me a book The Girl Who Reads on the Metro by Christine Feret-Fleury. That’s what book loving friends do — we send books. My friend, Ken, in Toronto, reminded us to support local bookshops, so on a website he posted, I ordered Lily King’s Writers and Lovers.

In some distress, I read that one of my favorite independent bookstores in Williamsport, PA was also asked to close. I wrote to Alissa and Nancy, my favorite booksellers there. “Send me a box of books,” I said. “Surprise me. You have never steered me wrong.” Last night, the box arrived: Hilary Mantel’s newest; picture books for me to read to my girls in my school; a treasure trove of new titles; fiction to break up Churchill’s war.

I am stockpiling stories. Again. In thinking about how to structure this long string of days at home, I cannot find my rhythm. I feel like a drab hummingbird, dressed in a bathrobe, unable to settle, fluttering my wings a million beats a minute as I move from kitchen to newly organized home office to bed to our family room. On Instagram, I admire those who have adopted gourmet cooking and exercise routines. I have not. Rather, I saturate on social media, on headlines that terrify me, and then I do the dishes, prepare meals, talk to my adult daughters in Manhattan, gaze at all my new books piled up waiting for me in the dining room. One of them surely contains all I need to manage through these peculiar days.

Then, I read a meme on Instagram that startles me into optimism. Anne Frank and her family hid in a tiny space for 761 days, hiding for their lives. I can manage privileged disruption. We have light and food and heat and water and Wifi. We have community and resilience. We have one another. And we have books, loads and loads of books—new titles that call us, familiar titles to re-read to comfort us, fiction to hide out in, non-fiction to help us retain perspective. We have the long arc of history, the lessons of the Spanish flu. We have remarkable doctors and nurses working to keep us healthy, and we have the opportunity to hunker down, to stay away from one another, to help by maintaining social distance and losing ourselves in stories.

In a few days, I will settle, find a new routine. When events upend us, it is normal to feel unsettled, to find our prior coping mechanisms unsatisfactory, but in my fifty-nine years, reading has never failed me. My books wait patiently, certain of my return.