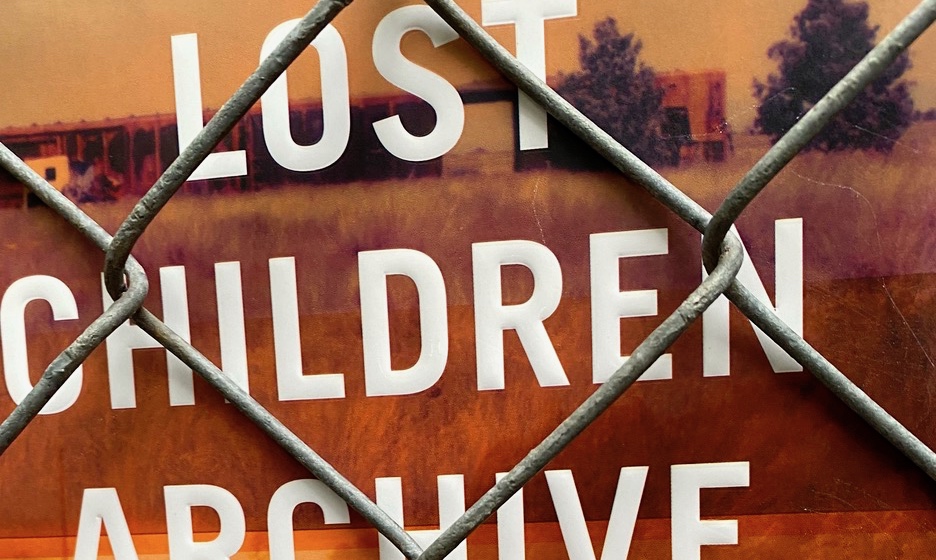

In a book that shrugs off novelistic conventions yet embraces familiar themes of narrative (the epic journey, the loss of innocence, the intersection of personal and political), Mexican-born writer Valeria Luiselli writes a nearly perfect response to the nearly unbelievable crisis of undocumented children crossing America’s borders. Lost Children Archive’s multi-layered collage of stories, sounds, photos, and voices is itself a documentation of one semi-autobiographical family heading west to Arizona from Manhattan in an old Volvo, a husband and wife growing more distant from each other, and two remarkably realized children, a boy just turned ten and a five-year-old girl. The couple (each a parent to one of the children but not to both) met four years earlier while recording a soundscape of all the languages spoken in New York City, and the reverberations (literal and symbolic) of their chosen careers abound as they journey west in search of ultimately incompatible projects: the husband to record “an inventory of echoes” of the last Apaches and the wife (and first narrator) to research a documentary about unaccompanied children at the border. The book is divided into four main parts, themselves broken into short, titled sections that serve as archival material for the family’s road trip, a book within the book, the “lost children” in all of their permutations, and the novel itself.

At first, the wife is invested in the plight of children at the border because of her acquaintance, Manuela, whose two young daughters have traveled alone through the desert, their mother’s phone number sewn into their dress collars, only to be captured and slated for deportation; however, before they can be returned to Mexico, they disappear. In the car and various motels, the family reads aloud from a fictional book (written by Luiselli) entitled “Elegies for Lost Children” which tracks in poetic and disturbing detail the flight of seven children in the predatory care of a coyote, paid to lead them through hell: swollen rivers, perilous jungles, a beast-like train, searing deserts. As they pass through towns of the American West named Poetry, Truth or Consequence, Geronimo, the family listens to Lord of the Flies on tape, another dystopian tale of lost children, after rejecting Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic father/son book The Road as too dark, though its first lines repeatedly fill the car. The father tells of the last Apaches to surrender, including stories about the Eagle Warriors, fierce children who survived alone “like small gods.” There are relentless radio broadcasts about ICE raids, disappeared migrants, and political rants. At one point, the family bears witness to deported children boarding a plane. How can anyone do more than merely despair at the litany of vanished, vanquished children? Luiselli (and her stand-in, the wife) believe that empathy comes through reenactment. The children play games in the backseat: “Perhaps their voices were the only way to record the sound marks, traces and echoes that lost children left behind,” whether the Apaches, Manuela’s girls, the seven from “Elegies,” or, in a heart-stopping development, the disappearance of the specific children who have become beloved and real to us.

Halfway through the book, the boy, precocious yet utterly childlike, takes over the narration, and we see some of the same scenes through his eyes, and register the effect on the boy and girl of a dissolving marriage; a fracturing family; a litany of exciting, horrifying stories of courage and expulsion, the mixture of fiction and facts. In a brilliant literary feat, the narratives of the two books (the one we are reading and the one they are reading) and the stories contained within merge into a 20-page single propulsive sentence that chronicles a harrowing, hallucinatory climax. Events we have kept at a distance are reenacted, and the stories we have heard, both “real” and imagined, mirror and blend. Echo Canyon plays a role both literal and metaphorical, and the many echoes of ghosts; voices; stories; past, present, and future lives bounce off each other, returning to our ears, redoubling, refusing to be silenced. Luiselli’s experience as a translator for undocumented children and her prior nonfiction work complement the narrator’s instinct to archive the personal and the political, and both voices are anguished: “All I see in hindsight is the chaos of history repeated, over and over, reenacted, reinterpreted, the world, its fucked-up heart palpitating underneath us, failing, messing up again and again as it winds its way around a sun. And in the middle of it all, tribes, families, people, all beautiful things falling apart, debris, dust, erasure.” As a documentation of American history and present, The Lost Children Archive works as a palimpsest layering language, sound, story, echoing and projecting with wrenching sadness, surprising humor, classical and current allusions, all with the resonance of great literature: to ensure that we empathize, that we hear, that we are moved to resist the erasure.