Dear Fellow Readers,

Do you feel a thrill when a notification pops up in your inbox telling you a book you requested has arrived at the library? When that happens to me, I feel a tiny quiver of anticipation, scheming about how to swing by the library to pick up my treasure. Our county library system is fantastic. When I read the New York Times Books Review and request a title on Sunday, I often have it by Tuesday. And, given my intention to buy fewer books and therefore possess fewer books, I am lucky to have access to such riches. But the intention to acquire fewer books is sometimes at odds with old habits. I love owning books, having them line shelves, several deep. I like being surrounded by books. I think piles of books, read and unread, characterizes my decorating challenge best — not because I wouldn’t like to live in a pristine, uncluttered environment, but because I like books more than order. I like looking up and seeing Lady’s Maid on a shelf and thinking about the Brownings’ unlikely love story. I like my shelf of Mary Oliver volumes nestled near my collections of works by Naomi Shihab Nye, Linda Pastan, Mary Jo Salter, Emily Dickinson, T. S. Eliot and Ross Gay.

People who love me have gently suggested that I may be addicted to books. It’s true that books are my drug of choice and have been since I was a little girl. Sidelined by asthma, I escaped into worlds of words. Reading was my superpower. I preened at being called on to read aloud the longer or harder passages in class. I knew I was a good reader. Books were to be devoured, remembered and acquired. I read fast and I remembered what I read. The more I read, the more I wanted to read. Up late in the middle of the night, after my mother had administered the revolting pink syrup teaspoon of Quadrinal to quiet my wheezing and had returned to her own bed, I piled books next to me on my bed for comfort.

I lost myself in the sequel to 101 Dalmations called The Twilight Barking, that Disney had not adapted, imagining Ponzo and Perdita’s clever outwitting of Cruella DeVil. I climbed the alps with Madge and Joey in the Chalet School books, a long series set in a boarding school by Elinor M. Brent Dyer. I imagined fasting for Yom Kippur and dusting to find buttons along with the sisters in the All of a Kind Family series by Sidney Taylor; I wanted to be a nurse because of Cherry Ames. In my mind, I was a lady-in-waiting for Miss Bianca, an aristocratic white mouse, and in all the historical fiction that followed, I imagined myself in the middle of the story — not a reader, but a participant. I was Jo March, writing wild stories and bobbing my hair to care for my family. I imagined founding a school of my own as she did with Mr. Baher. I read and re-read The Secret Garden and A Little Princess. Falling asleep with a stack of books along with the requisite stuffed toys (illicit because of my asthma and allergies, but there all the same) made me feel surrounded by friends, by possibilities.

At Ludington Library and at school, the librarians knew of my voracious appetite and tried to keep me in books. Each November during the church bazaar, my mother would find me rummaging through the donated cartons of books, seizing volumes that were more my mother’s vintage than my own: Maida’s Little House; Honeybunch, the Patty Fairfield series set in Edwardian Manhattan, a landscape that felt eerily familiar to me decades later when I moved to NYC to teach in an all girls’ school on the Upper East Side. Books were what I wanted for Christmas and for my birthday. They were rewards and gifts. I had a wish list at The Country Bookstore in Bryn Mawr long before Amazon had even been dreamt of. Each summer, before we left to spend three months with our grandparents in a little town far away from libraries or bookstores, Mother allowed me free rein at Ardmore Paperback, rarely denying me armfuls of Dell Yearling paperbacks.

Once in college, my obsession with reading threatened my schoolwork. In the midst of finals, I was deep into M.M. Kaye’s The Far Pavilions. My roommate, Edith, had to intervene, hiding the thick paperback until I had studied for and taken all of my exams. I never stopped reading as a teenager or adult; the habit was too ingrained, too essential to my well-being. As soon as each baby got the hang of nursing, I read while tending to my infants. On planes, my guilty pleasure is my decision to read only fiction; I don’t love being away from my family, but a new novel makes any trip more bearable. My children have exhorted me to use a Kindle. They think it’s silly that I stuff my bag with books, but I do not want to read on a screen. I love the feel of a real book, the cover, the smell, the weight.

A deep-seated fear of being marooned without enough reading material fuels my acquisition of books, ones borrowed from the library and ones purchased. If steamer trunks were still in vogue, I would fill one with books and relish a transatlantic crossing for all the time it would afford me to read, undisturbed! At any time, I have five or six books going at once: a novel or two, some books centered on education or leadership, at least one book about writing, and a young adult title recommended to me by a student. I pile the books by my bed, occasionally toppling the tower. Each year, I try to purge titles from my library that I will never read again, starting a book swap at my school, so I feel less guilty about any hardbacks that have crept in. We did manage to get rid of several copies of Joyce’s Ulysses that seem to have bred in the decades following college. Even I acknowledged that one would be sufficient.

But it’s hard for me to part with stories I’ve loved. I always fantasize having the chance to re-read novels, imagine urgently needing to look up a passage in the middle of the night. Once I read somewhere that books like to be handled; if I made an effort to touch each book every year with a dust rag in my hand, I could both diminish the dust in our home and give neglected volumes the attention they deserve. I tell my son I am going to write about my fear of being without books to read. He suggests I reference the TV show, Hoarders. I’m indignant. But he’s right. I have a such visceral fear of being without enough titles to read that I stockpile books.

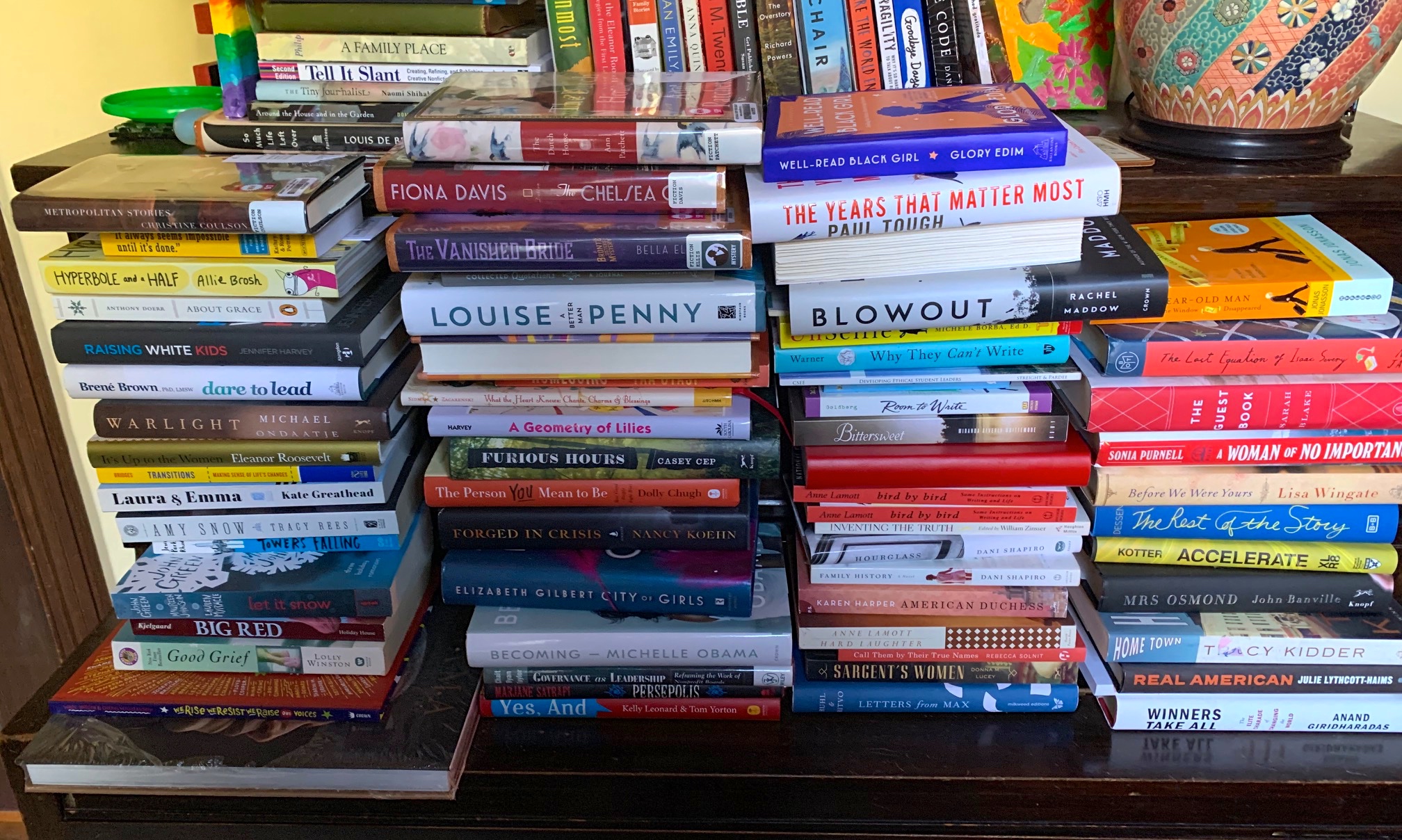

Things are slightly out of control. I’ve piled more than fifty books on our apartment sized piano. My husband’s father bought the diminutive piano for his daughters when they arrived from Berlin. I think about that gesture — a piano that symbolized the comforts of the life they had known, perhaps an extravagant gift intended to bring comfort. No one in my house plays the piano. We could replace the piano with a bookshelf. Instead, I like that it has become a repository where my books wait patiently, library books and books I own jumbled together. The stacks of books make me feel safe. There are plenty of volumes to choose from. The piles ebb and flow. I’ve stopped worrying about running out of titles. There will always be more stories to read than the time I have to read them. What a delicious problem of excess in a season of excess.