How does Anna Burns make entertaining art from life based on a particularly violent period of “The Troubles” in 1970s Belfast? Mainly, she does it by using stylistic quirks that are utterly original and often funny. For example, she eschews naming of any kind, since, in an oppressive society that has even stolen your language, it’s safer to avoid naming of anyone or anything.

Everyone in this novel is nameless. Instead we have our nameless protagonist’s three “wee sisters,” her “maybe boyfriend,” friends such as “Tablet Girl,” who slips pills into the drinks of those she dislikes, “pretend brother,” who is on the run, and the British, referred to as “enemy soldiers from across the water.” In a world where no one can be trusted, it’s safer to be nameless.

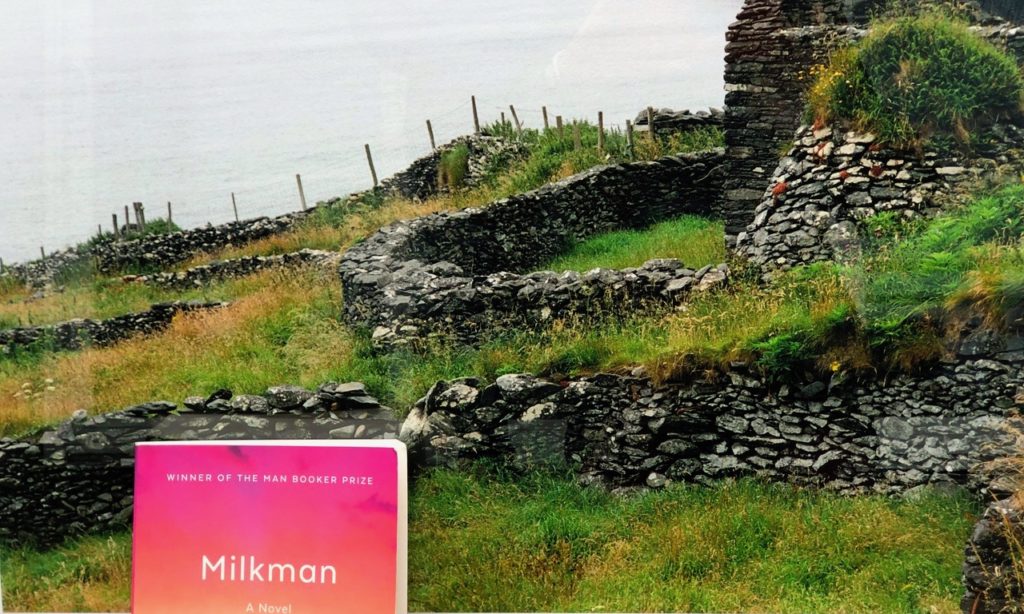

The author, Anna Burns, seemed to come out of nowhere to dazzle readers and win the esteemed Man Booker prize in 2018. Like other great Irish fiction writers, she has the gift of spinning a gripping tale in compelling language that manages to be funny, though the historical events she obliquely and namelessly references — the Belfast riots, Bloody Sunday, the disappearance of Jean McConville — are anything but.

Burns gives us the denouement of Milkman in the first sentence: “The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died.” In this world of oppression by the British, with the help of their Protestant collaborators in Northern Ireland and the resistance populated by native paramilitary organizations, it’s hard to know who to trust, so better not to draw attention to yourself. But our nameless narrator chooses to read-while-walking, and in so doing attracts the attention of milkman, a mysterious stalker, who tracks her through the novel. Trying to avoid paying attention to her environment by reading nineteenth-century fiction, our first-person narrator stands out instead, eventually lumped with the “beyond-the-pale” people shunned by her community.

Burns fuses humor with a sense of dread to create a work that reminds me of writers like Gogol, whose use of grotesquerie and a sense of the absurd is similar. This mixed mode undercuts the feeling of paranoia, and leaves us with uncertain emotions. Are we to laugh or cry about the narrator’s predicament? Her mode is humor, but she also creates an increasing sense of dread, skillfully combining the two.

Her sense of the absurd also carries us beyond difficulties with her style: page-long paragraphs and long sentences that often mix modifiers (“a man-overboard person,” for example). The dominant impression is of a writer in love with language in the way that great Irish writers from Joyce to Banville and Heaney have been. Open any page of this novel, and you can find ceremonies of pure joy in language. For example, this sentence about our narrator’s father’s depression: “ …da had had them: big, massive, scudding, whopping, black-cloud, infectious, crow ,raven, jackdaw, coffin-upon-coffin, catacomb-upon-catacomb, skeletons-upon-skulls-upon-bones crawling along the ground to the grave type of depressions.” Yes, the topic here is depressing. But the sheer exuberance of language — the result of excess and the piling up of adjectives, nouns, and verbs — creates a sense of comic overload. Perhaps it’s an act of resistance to bend language, breaking laws of grammar, diction, and moderation when you must write in the language of the oppressor.

To learn more about the story of Jean McConville, from which Burns took very specific details, see Patrick Radden Keefe’s Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland. This historical examination of the unsolved murder of Jean McConville resonates even today, tied up in sealed police records in Boston.

“The past is never dead; it’s not even past,” Faulkner famously said and Milkman illustrates.