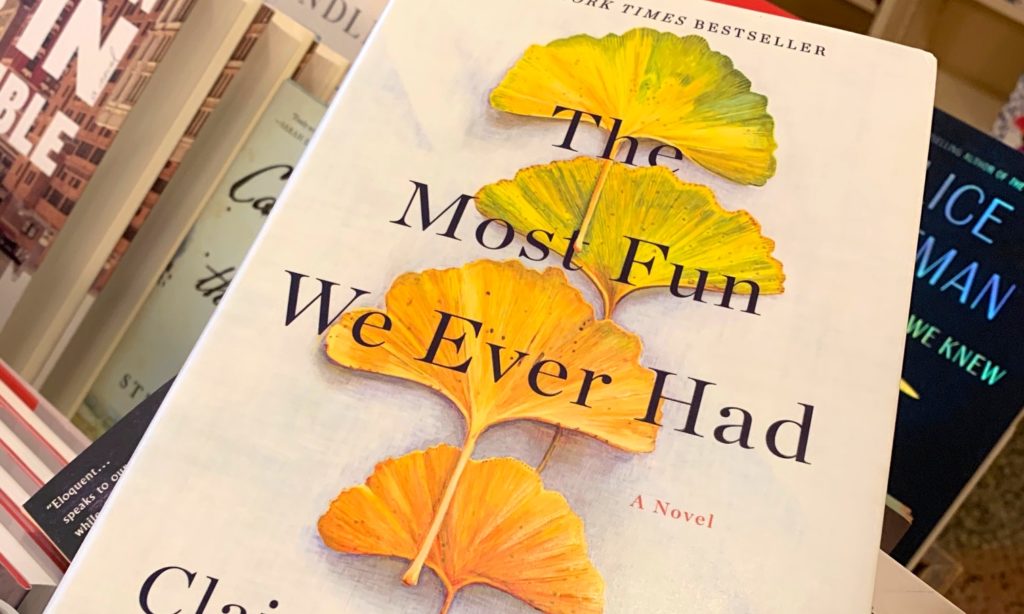

At a friend’s house in late summer, I pick up a book with ginkgo leaves on the cover, the three green and yellow shapes beckoning me.

“Have you read it?” I ask my friend.

“Book club,” she answers.

It’s a new book for me, one I haven’t read about in the New York Times or online. I type the title — The Most Fun We Ever Had — into my library request site and see that I will have to wait a long time; I’m about 400th on the list. That same week, I learn that I can listen to books in the car without loading CDs and worrying I will drive off the road as I scramble to pop one CD out and open the hard plastic box to retrieve the next one. My husband explains that Audible lets me listen to books that I download on my phone. And I have credits — imagine! I don’t really understand what Audible is, but I acquire The Most Fun We Ever Had and suddenly, this luddite has entered a whole new world of audio books.

Listening to a book is different for me than reading it, but it’s a good kind of different. I’m a fast reader, often devouring books in a gulp. Listening rations how fast I can proceed, allowing the plot to unspool more slowly. I might only be able to squeeze in one chapter on my way to the dry cleaner. Soon, I am in deep, loving this novel about a modern family — Marilyn and David Sorenson, their four daughters, their complexities, their drama. I confess to lingering in the driveway to hear just a few more pages.

The Most Fun We Ever Had is a well-structured story that shares the characters’ backstory adroitly, never all at once, but in reveals that feel well-timed, well-placed. Structured in a way that moves back and forth in time and allows different characters to be the focus, it is never hard to follow. Like all generational blockbusters, there is sorrow, but there is also a deep understanding of family and what makes us human and pushes our buttons in a family.

Lombard knows a lot about what it takes to make a marriage work, understands loyalty and rivalry between sisters and motherhood and grief and guilt and fear. The sisters are delineated in ways that felt believable to me, each occupying a different role in their family. I was particularly compelled to Wendy, the tortured eldest, who is arch and cynical and tough, but who, we understand as the story unfolds, has reason to be all those things. Violet, whose long ago choice propels one plot line, is that high strung control freak I recognize. Liza is brilliant and lonesome in her partnership with a man who cannot get a hold of his depression, and Grace, the youngest, feels the weight of expectations in a family of high achievers. The boys — Jonah — a sulky, wry adolescent and Wyatt, a wide-eyed five year old — are skillfully drawn, though to explain their relationship would be a spoiler. And the love interests each sister has are also real, sketched in less detail than the girls, but believable.

This is a hugely satisfying story with characters who interested and moved me. Yes, there are lots of issues — contemporary fiction is loaded with issues — but these particular dilemmas felt plausible, as if your neighbor or your sister or you might be coping with similar stresses. I did not feel Claire Lombard invoked cheap tricks, any deus ex machina theatrics. The novel pivots on a secret, but even the choice that led to that secret seemed possible to me.

Particularly believable for me is the characterization of Marilyn and David’s marriage and the ways in which the girls deify their parents’ relationship. It is true that that this couple loves each other over many decades, continues to be in love and to express their affection to the horror of their children, but the reader (listener) knows their journey has not been without conflict and tension and fatigue. The teenage and adult girls are grossed out by their parents’ gooey embraces, kisses, touches, even as they rely on their parents for advice and help and understanding. David is the quiet, steady doctor father. Marilyn is absorbed with parenting four daughters and then pursues her own entrepreneurial dream, buying a hardware store. When David retires, he takes up the study of trees and plants; the ginkgo tree is both a symbol and a prop in the story over many years, as much a part of the setting as is the city of Chicago.

I loved the moments that Marilyn and David talked about their girls. “How worried should we be about Liza, on a scale from one to ten?” Marilyn asks David. When he answers, “Seven,” she is alarmed, but he explains that his worry for is youngest is always at a five. I laughed, thinking of similar conversations my husband and I have had about our three children over the decades.

I have the sense that all these characters are continuing to live their lives, even now that I’ve turned the radio off.