Lately, I seem haunted by a handful of contemporary short stories. You know the kind I mean––those stories who name so precisely, so eerily what it is to live in these times, that they float their poignant imagery in and out of your days long after you’ve read them. I’m thinking especially of Adjei-Brenyah’s “The Finkelstein 5” and Roupenian’s “Cat Person.” Joanna Pearson’s beautifully crafted 2019 collection of stories, Every Human Love, however, has held a different power over me.

In her best stories, at some point I actually felt a growing sense of dread. I wasn’t sure I wanted to go on, wasn’t sure I wanted to learn who was knocking at the front door or what was bumping around the attic. In “Rumpelstiltskin” the inevitable arrival of the titular character actually sent ripples of terror up my spine. What makes many of these stories more than simple horror stories, however, is Pearson’s use of a psychological Valley of the Uncanny: protagonist and reader alike struggle to determine whether such terrors are without––or (cue the shivers) within.

This is Pearson’s first collection of short fiction, having published a young adult novel in 2011 and a book of poems in 2012, which won the Donald Justice Prize. She is a practicing psychiatrist in North Carolina, and this writing showcases both her medical and literary foundations. Hospitals and diagnoses imbue the collection. Most notably, though, there is a distinct poetic quality to these stories––and not just on account of Pearson’s nimble precision with language, which is ubiquitous, for they often read more like incomplete anecdotes, hesitant with plot, but rigorous in surprising moments and tense air. They nearly all end lyrically, as one might end a poem, rather than narratively.

Pearson’s instinct to let the ghosts of her stories hang in the air at the end, instead of burying them tidily, is occasionally frustrating, but decidedly beautiful, such as the ending to “Ouro Preto”: “And even now, years later, I see him, the image seared into my brain: standing in the setting sun, ugly-magnificent on that hillside, with his big, clumsy hand outstretched, radiant with want.”

Some more philosophical moments, such as this one from the story, “Gifts,” I wanted to read a few times: “I watched Lynn check out, efficient, shoulders squared. I watched her push her father out the yawning automatic doors, the two of them moving like a single organism. There are some currents that run harder and deeper than love, I thought then. Some things calcify in a way that can’t easily be broken. And the universe, tectonically slow but indefatigable maintains its own destined frictions. Let love try to compete with that.”

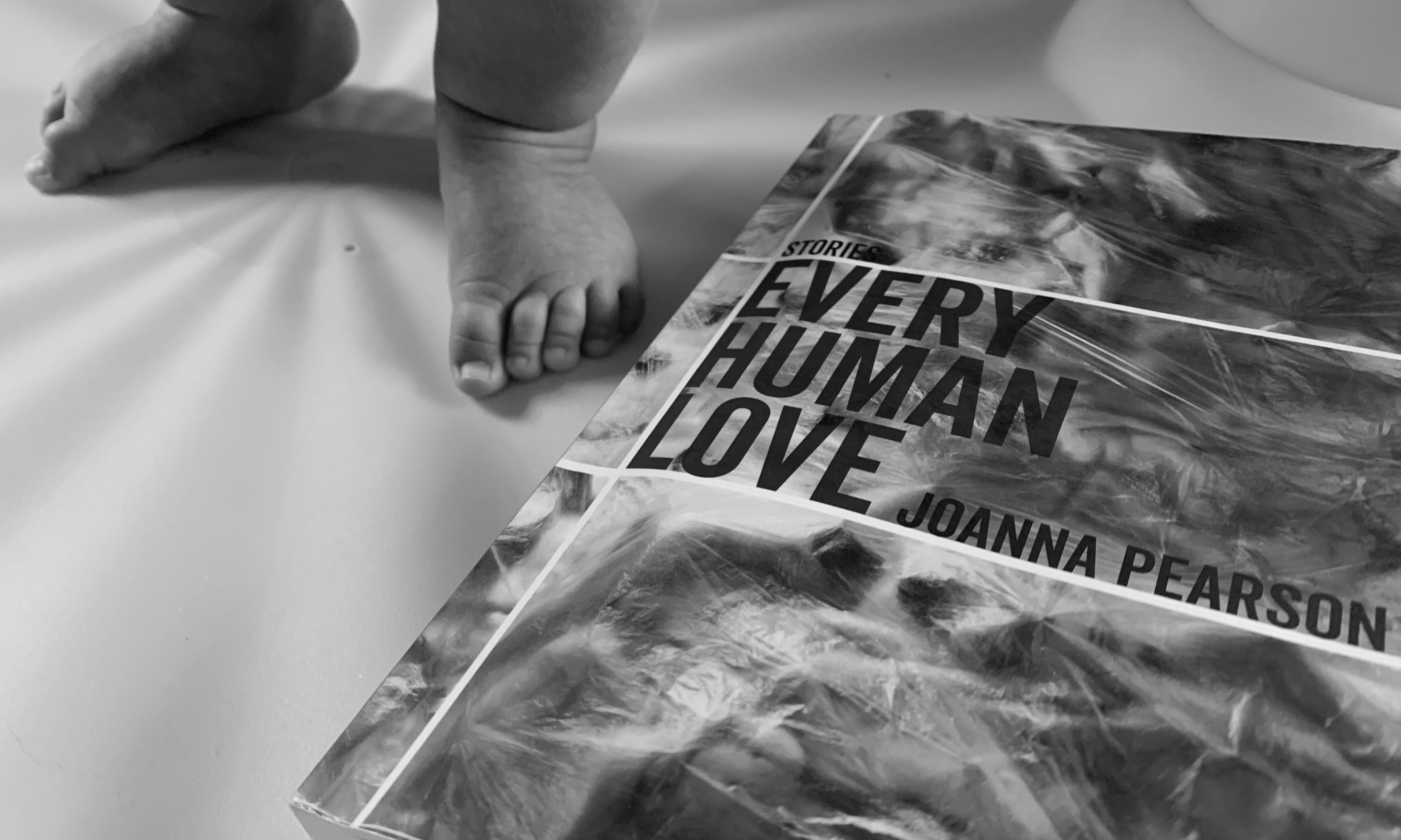

Pearson’s stories are dark, efficient, and often funny, and I had to read them slowly, and not all at once. I made the mistake of beginning the collection while up late at night with my newborn. The first story, “Changeling,” is about a bone-tired new mother and the eerie unknown of what happens when she falls asleep. Whoops. Or perhaps it wasn’t a mistake at all. Despite how long it took me to get back to sleep (lines like “she realized then why the room was so cold” running through my head), I’m always grateful for literature that prods the viscera, that lingers.