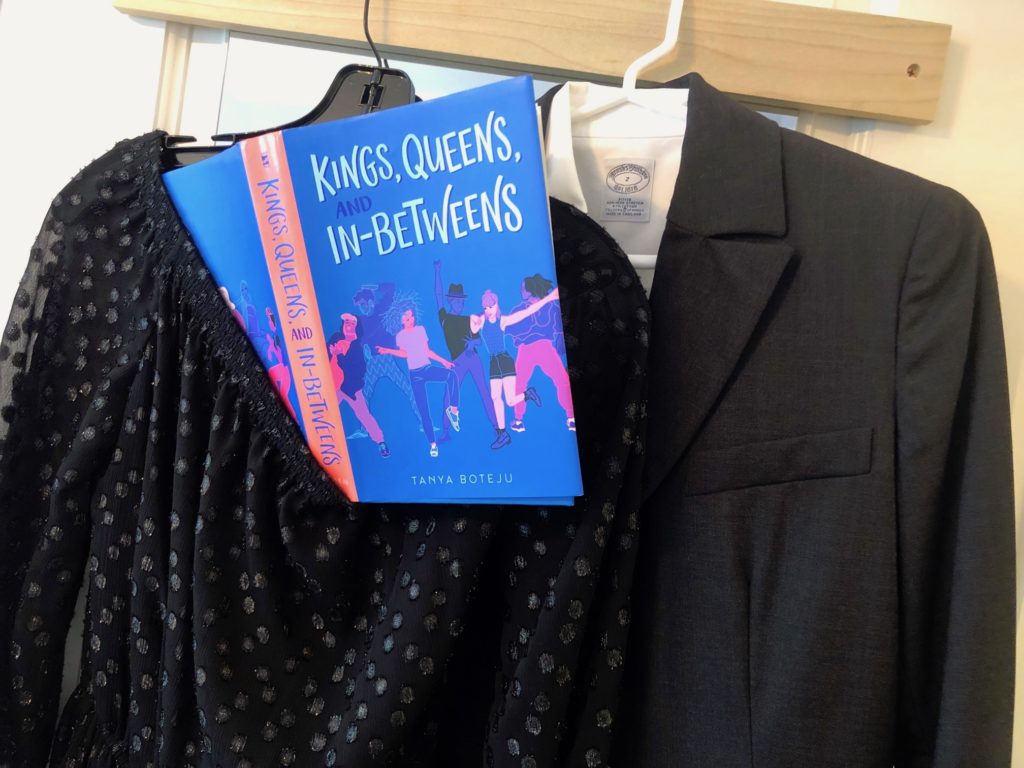

For two summers, I sat through graduate school classes with Tanya Boteju. You might think, based on the fact that she has just published her first book of fiction, that we were studying creative writing. Not so — Tanya and I were studying educational leadership. I mention this because it is important to understanding why her book, Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens, has layered significance for me. Because we were in a program dedicated to school administration, it didn’t occur to me that Tanya was not only a teacher and aspiring leader but also a writer working on her first novel. Because of my assumption, I missed out on the chance to learn about her creative projects or collaborate with her until later. That’s essentially what Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens is about: the things we miss when we make assumptions about what we and others are interested in and capable of.

Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens tells the story of a funny, smart, and believably insecure adolescent named Nima who lives in small town and is in love with her friend, Ginny. Ginny does not, at first blush anyway, feel the same way about Nima. When Nima, lightheartedly depressed about her limited life experiences as she readies for her senior year of high school, stumbles upon a drag show at a local festival, her circle of friends widens while her assumptions about herself and others are exposed and challenged.

Nima easily falls in with a lively crowd for whom gender fluidity and same-sex love is not noteworthy. What is noteworthy, for Nima, is the way this group of people instantly accepts and celebrates one another. Deidre, a drag queen, and Winnow, a king, don’t bat a sequined eyelash as Nima fumbles her way toward greater self-realization. Instead, they humorously, patiently, and kindly help her find her footing. When Nima meets a butch Wonder Woman named Luce at her second drag show, Luce tells her, “You look like someone who’s dying to try something new tonight.” Nima can’t disagree and finds herself taking to the stage for the first time in an imperfect attempt at karaoke-style drag. This small taste of gender performance will plant a seed in Nima that continues to grow in surprising ways.

Boteju’s book refreshingly side-steps and even revises stereotypes and tropes. In her search for self, Nima is not reckless and her family and friends are not horrible to her. Even the book’s villain, a bully named Gordon, turns out to have struggles of his own that Nima can empathize with, while sub-plots involving Nima’s mother, father, and their friend, Jill, resonate naturally with Nima’s story. Boteju writes Nima’s story with a light but very skilled touch. When I finished reading Kings, Queens, and In-Betweens, I had a deeper understanding of not only how limiting our assumptions about ourselves and others can be, but also how without intention in noticing them, they can take root and proliferate in us.