Being an observer of an illness is an experience that is both unbelievably intimate and incredibly detached. There are moments in which it fills you with hope, only to leave you feeling hopeless. There are moments in which it fires you up to help, only to leave you feeling helpless. I’ve been the observer. I’ve seen an illness—cancer—poison the body of someone I love, slowly wearing it down, down, down—slowly wearing it down until there is nothing left.

This, too, is how Miriam, Tamar, and Paula experience cancer in Judith Vanistendael’s graphic novel When David Lost His Voice. David—father and husband—is sick. He has a tumor on his larynx. Miriam, Tamar, and Paula, the three people who make up the center of David’s world, are observers of his illness, feeling not the pain of the cancer itself, but the pain of survival in a world where they will be haunted by grief.

In its cruel way, however, grief haunts Miriam, Tamar, and Paula even before they experience true loss. As he is being diagnosed, Miriam, David’s adult daughter, gives birth to his first grandchild, who she will raise as a single mother. Paula, David’s second wife, is overpowered by the shadow of loss that will soon attach itself to her. She expresses this fear through her art, which becomes filled with images of death. Tamar, David and Paula’s nine-year-old daughter, believes that maybe her father will live if she mummifies him and puts his soul in a jar. She undertakes a journey with her friend Max to figure it out.

While the three females in his life are each given a chapter to express their relationships with his illness, the novel ends in David’s voice, a reminder of life’s cruelty: Vanistendael gives David a voice as he is—literally—losing his.

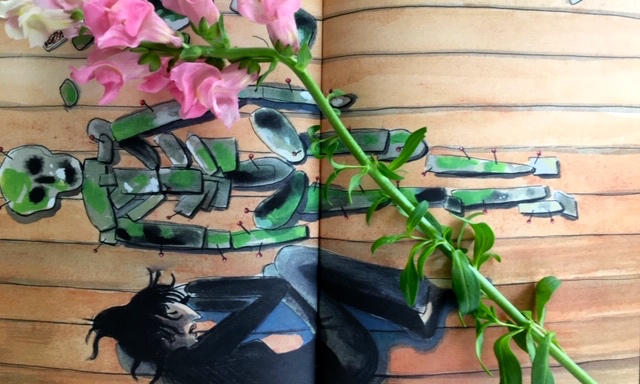

Vanistendael’s gift is the way in which she allows her readers to become observers, too. The novel starts with a prologue: a doctor giving David a clinical description of his diagnosis, diagrams and all. This narrative stands in stark contrast to the evolution of images in the prologue, in which David sees himself, naked and skeletal, rising into the arms of his halo-wearing childhood nanny, who gives him a “lucky charm, made from divine light [that’s] good against all sorts of troubles, like pessimism, dark thoughts, and depression.”

And so, with this small token of hope, Vanistendael leads us into her story. Using sparse narrative and indelible watercolor panels contrasted, occasionally, with pages of stark black-and-white, Vanistendael’s blurred colors and lines pull the readers’ emotions from page to page.

I shy away from cancer stories. They hit too close to home. But Vanistendael’s novel is lyrical and anything but sentimental. The softness that so often accompanies stories of loss is not present in the lives of David, Miriam, Tamar, and Paula. They have each other and Louise, Miriam’s baby girl, to help them remember that there is still life left to live.