It was 10:30 on a Tuesday in November in New Haven, and my professor, Langdon Hammer, was reading aloud from Frank O’Hara’s Personism: A Manifesto. “Personism” is an excellent essay to read aloud to a lecture filled with twenty-year-old kids at Yale early in the morning because it possesses the exact flavor of cynical New England wit that every one of us wishes we were jaded enough to flash.

The whole room was awake and laughing. And then, everyone went quiet. Professor Hammer took a breath and read O’Hara’s words in a gentle, steady tone: “I went back to work and wrote a poem for this person. While I was writing it I was realizing that if I wanted to I could use the telephone instead of writing the poem, and so Personism was born.” O’Hara is groundbreaking in that his poems are personal, but not confessional. They are complicated, and they are colloquial. They are conversations between two friends, Professor Hammer lectured us.

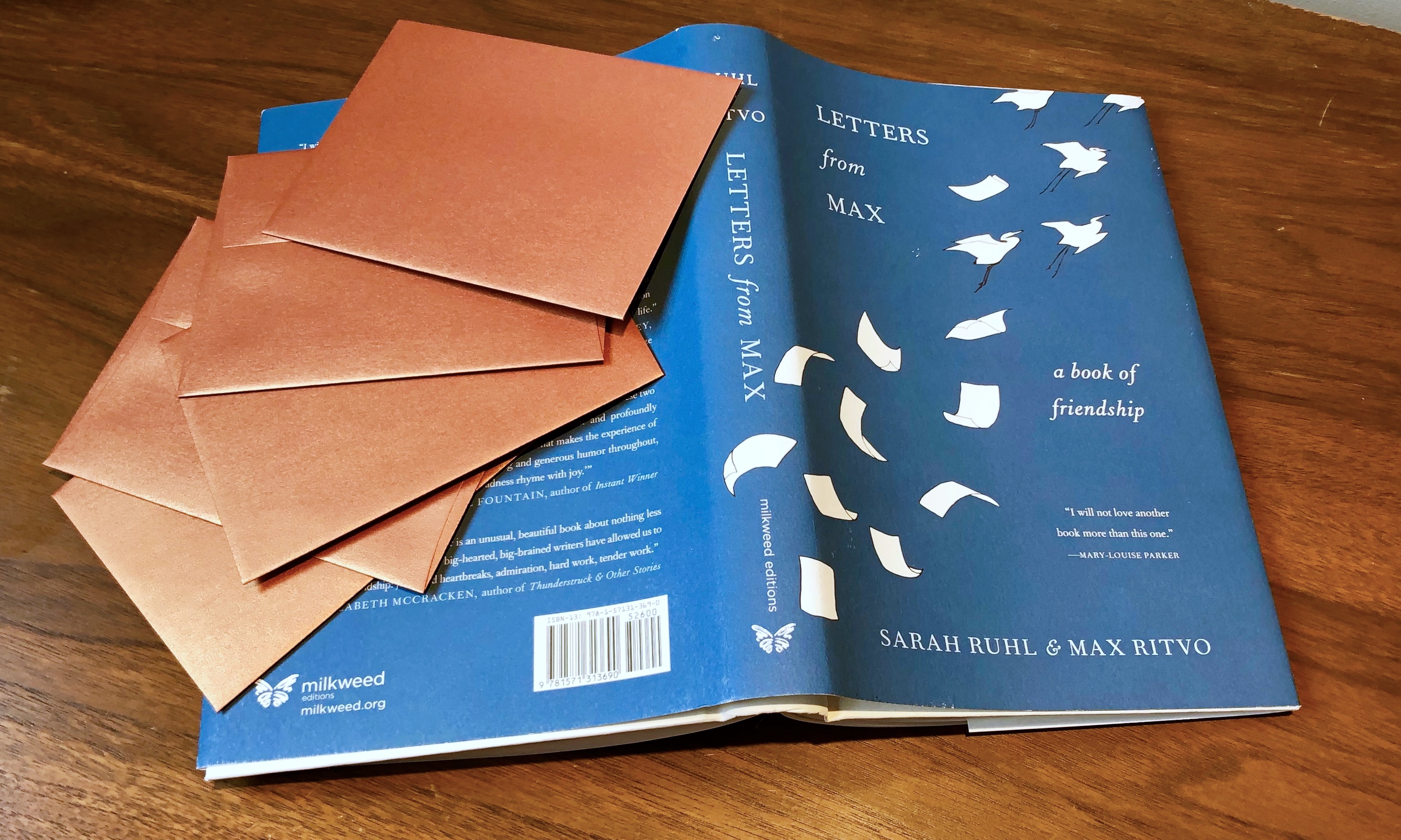

I spend a lot of time thinking about O’Hara’s mastery. I spend a lot of time trying to simulate O’Hara’s mastery. Most of all, I spend a lot of time trying to find books that contain the same tenderness, honesty, and humor that “Personism” lauds. When I read Sarah Ruhl’s new book, Letters from Max this winter, I thought, “Found it.”

In Letters from Max, the playwright, essayist, and professor at Yale School of Drama, Sarah Ruhl, reveals a correspondence through which she and the young poet Max Ritvo make art that is almost like “Personism,” but better, because instead of giving us only the poems produced through the pair’s correspondence, Ruhl gives us everything. The book is entirely composed of letters, poems, songs, emails, and recounted conversations between the pair, with short paragraphs here and there to string everything together.

Reading the book is like listening to a long phone call between Ruhl and Ritvo spoken solely in verse — perfectly in the spirit of O’Hara’s “Personism, ” it is never self-conscious, and it is always a bit silly. Part of what makes this narrative so exciting, especially to a college kid like me, is that this magical kinship is born from a mundane relationship. In Letters from Max, Ritvo is Ruhl’s student in her senior playwriting seminar at Yale. The pair, one playwright (Ruhl), one poet (Ritvo), sometimes two playwrights, sometimes two poets, sometimes just two people, begin emailing each other out of necessity. Ritvo’s missing Ruhl’s class to see a play — a good play — in New York. Ruhl gives him the okay and is impressed by his taste in theater. These logistical emails turn lengthier, more frequent. Soon, they are no longer just emailing each other, they are meeting after class. They are writing to each other. And then they are writing about one another. They are sharing soup.

As the pages of Letters from Max progress, the tether between the two writers strengthens and a sense of true spiritualism between teacher and student emerges. Max has cancer. He has had cancer since Sarah met him, and because of this, questions of afterlife are present throughout nearly each letter that the writers exchange. Ruhl and Ritvo share an infatuation with Eastern spiritual practices. Ruhl loves monks. Ritvo loves reincarnation. They each believe in the power of idols. All along, though, Ruhl and Ritvo are becoming each other’s idol. Their emails and phone calls to one another serve as daily devotions. The correspondence captures a divine, archetypal student-teacher relationship — Ruhl the Vasudeva to Ritvo’s Siddhartha in modern academia, in modern America, in modern friendship.

The true delight of reading Letters from Max is witnessing how closely the friends’ everyday conversations seep into the writing they produce. In one of her earliest letters to Ritvo, Ruhl writes, “Oh, and on the school of poets who surround you, I say: resist opacity. I think at the heart of opacity is fear.” After this proclamation, Ritvo and Ruhl’s poems to each other become progressively more courageous. The poems allude more and more to earlier emails and phone calls between the pair (that Ruhl so gracefully and graciously includes for us). And in including their correspondence Ruhl only further captures her desire, shared with Ritvo, to make poetry accessible and piercing to her audience in a way that so much postmodern poetry resists.

In each other’s words, Ruhl and Rivo find comfort, humor, and escape from the scourges of the world — cancer, conference calls — that plague them. But more than that, in each other’s words each writer finds his and her own voice. Max and Sarah’s friendship inspires us to throw ourselves tenderly, wholeheartedly, unabashedly into loving our kindred spirits. The pair prove that O’Hara really was on to something. Being a good, good friend is the best way to make good, good art.