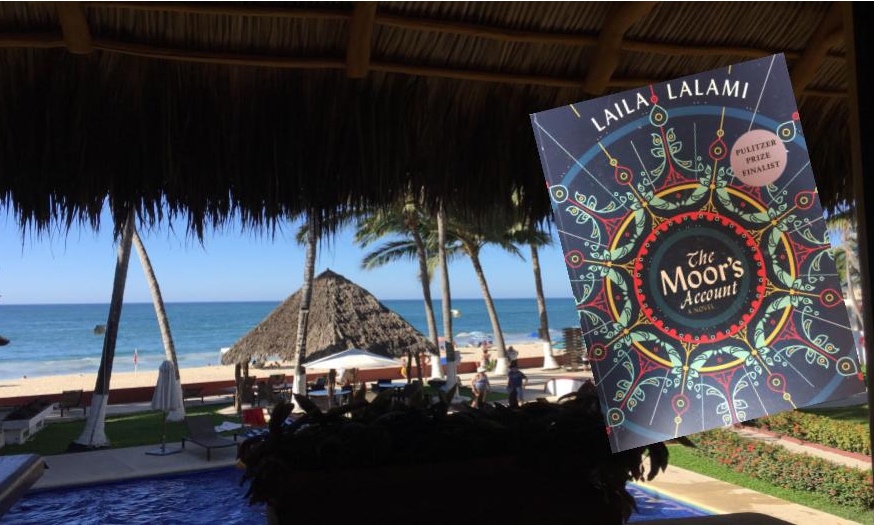

I’m always on the lookout for a great read, and recently a colleague suggested an article from The Guardian by editor-at-large Gary Younge titled “My Year of Reading African Women.” Younge claims he was “shamed by a gap in his reading” and “vowed to read only fiction by African women in 2018.” I went through his list of 19 novels and chose 5 to take on my spring break trip to Mexico. I finished The Moor’s Account, by Laila Lalami, in 2 days. Mexico was the perfect place to read this complex novel as the waves crashed outside my bedroom window and I was surrounded by and reminded of the language and the occupied land of the conquistadors.

The Moor’s Account tells the story of Mustafa, a Moroccan merchant, christened Estebanico after being enslaved by Spanish conquistadors. As Mustafa sails from Spain to Florida with a crew of six hundred men led by Panfilo de Narvaez, a Spanish conquistador, the trials and tribulations of this group of explorers begins. The novel shifts back and forth between Mustafa’s present captivity in La Florida and his childhood growing up in Morocco. We learn that Mustafa sold himself into slavery in order to save his family from extreme poverty and starvation. We move with Mustafa across what is now known as Texas where his contingent of explorer companions must adapt as they encounter tribe after tribe of Aboriginal people. An ongoing question of equality between these men of different colours and backgrounds continues: Mustafa’s servitude looks to be over, but his “owner’s” moral failings persist.

No single character in the novel escapes the author’s sharp eye and criticism, forcing readers to confront our own moral failings. What actions do we take when we encounter injustice? In extreme circumstances, do we behave in ways consistent with our beliefs? What stories do we tell ourselves to justify our behaviour?

The Moor’s Account poses as many questions as it answers. And the questions are ones that good novelists and 21 century readers will naturally ask themselves. Whose story gets told? Whose story is missing? What is equality? Who judges? The novel does not provide answers, but it does give us a glimpse into one possible way to be in the face of extreme and constant human suffering. Mustafa manages to find moments of serenity and peace in calamity, and he gives us a glimpse into that surrender: “I taught myself to savor what joy was within my reach. The world was not what I wished it to be, but I was alive. I was alive” (211).