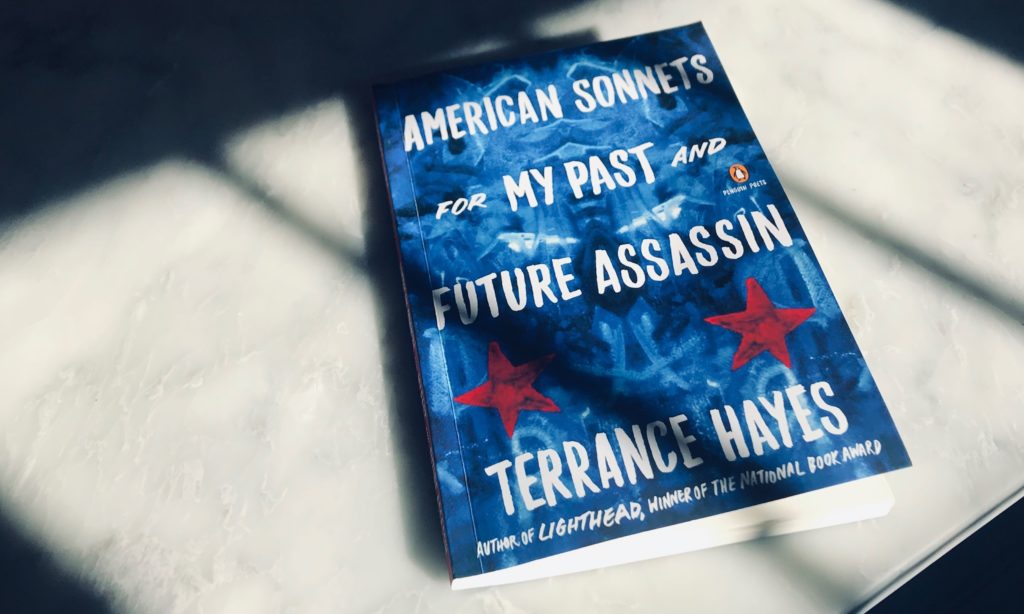

One of my most memorable courses in grad school was with the brilliant Mary Jo Salter, where we devoted the entire semester to the sonnet. A form that is, I discovered, inexhaustible – we discussed hundreds of the rectangular delights as love letters, rooms, beds, plowed fields, tombstones. In the 800 years since its invention in Italy, any poet worth his or her salt has contributed to the form’s celebrity and possibilities. The poet Terrance Hayes is no exception.

American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin is his seventh collection, and in these 70 identically titled poems, he honors the late Wanda Coleman in her imagining of an American sonnet. That is, a sonnet which breaks some classic rules of old-world decorum (Hayes’ are all unrhymed, uniambic-pentametered), but still maintains 14 lines of similar length, a volta (that change, that turn of direction, that surprise you’ve been waiting for), and an urgency in its forced compression and musicality.

How very American is that? In Hayes’ often politically charged sonnets there is, additionally, a swooniness, an eager wooing of the American consciousness:

Something happens everywhere in this country

Every day. Someone is praying, someone is prey.

Probably blindness has a chewed heart

In its belly, or a gate opening upon another gate.

Hayes has said that he wrote the first of these sonnets the day following the 2016 election. Many are invectives against the president, whom he often refers to as Mister Trumpet. Sometimes his words are high-spirited (Are you not the color of this country’s current threat/ Advisory? And of pompoms at a school whose mascot/ Is the clementine? . . . And of Caligula’s copper-toned/ Jabber-jaw … Pomp & pumpkin pompadour); sometimes they are more damning (You are the color of a sucker punch,/ The mix of flag blood & surprise blurring the eyes, a flare/ Of confusion, a contusion before it swells & darkens). Sometimes his epithets gratify in their balancing of play and rage:

The umpteenth thump on the rump of a badunkadunk

Stumps us. The lunk, the chump, the hunk of plunder.

…

The umpteenth boast

Stumps our toe. The umpteenth falsehood stumps

Our elbows & eyeballs, our Nos, Whoas, wows, woes.

These sonnets are chock full of tongue-in-cheek witticisms and arresting puns. But somehow––and this impresses me tremendously––Hayes avoids any semblance of flippancy or self-aggrandizing acrobatics. He seems paradoxically both gravitas and lightness. In one of my favorites, a curse to an unnamed subject, he brilliantly creates an image-pun from one of America’s great shames. He builds the setting by slowly peppering the first half of the sonnet with references to a bird trapped within a high school gymnasium. Harmless enough. But then, he completes the poem:

I make you both gym & crow here. As the crow

You undergo a beautiful catharsis trapped one night

In the shadows of the gym. As the gym, you feel the crow-

Shit dropping to your floors is not unlike the stars

Falling from the pep rally posters on your walls.

I make you a box of darkness with a bird in its heart.

Voltas of acoustics, instinct and metaphor. It is not enough

To love you. It is not enough to want you destroyed.

The collection often paints a picture of a country at war with itself, a country of moral ambiguity, taut with condemnations and celebrations, curses and blessings, rages and contemplations. Subjects range from Confederate statues to Girl Scout cookies, from Dylann Roof to Derek Walcott, from inadequate fathers to tattooed lovers, from the n-word to orchids.

I recommend reading these sonnets in a one sitting. Not only are you are keenly aware of the presence of a great mind, but themes, images, and lines repeat frequently––the book reads like a musical medley. One which, like the sonnet form itself, feels inexhaustible in its delights.