Once upon a time, the prospect of turning 30 terrified me. I supposed that I would fade into the wallpaper the moment I left my twenties; my skin would wrinkle then sag, and I would immediately become a fairy tale crone. Imagine my surprise and delight when I didn’t explode into a pile of dust at my birthday party. I felt strong and self-assured. I decided to celebrate this entree into my third decade by training for a marathon. I ran for miles and miles along Pineville-Matthews Road. As my heart pumped, as I picked up speed, I felt invincible.

And then a horn would blare, and some… man would hurl some lewd observation about my body out of the window of his car. Or, some different man would run alongside me as I panted through my 20th mile and tell me I was beautiful and ask me for my number. In moments like those, I wished to be invisible–or to at least know the safest way to protest, to say no. In moments like those, I wished I could wave my hand and make those creeps disappear or turn into slugs.

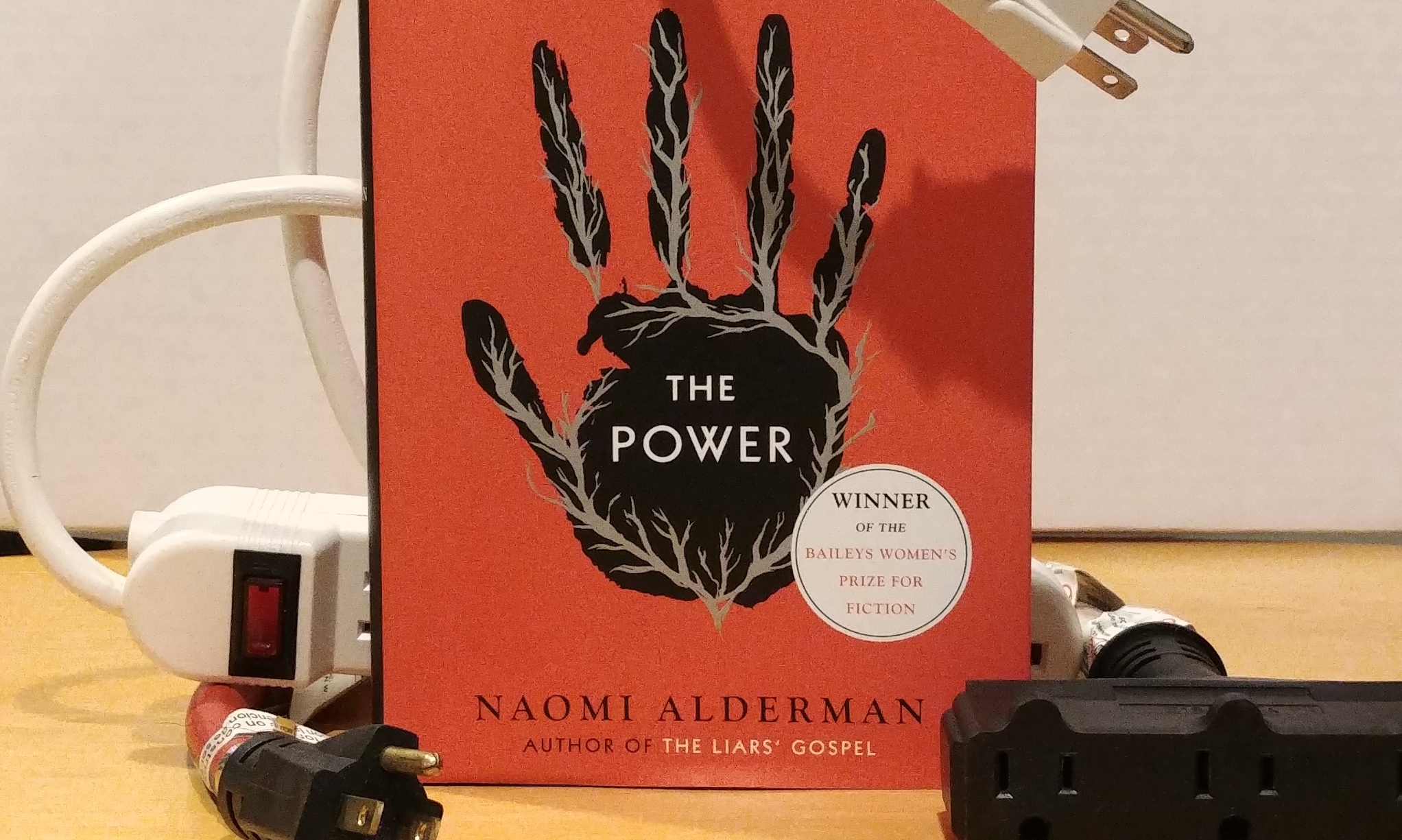

Reading the opening chapters of Naomi Alderman’s The Power returned me to those runs marred by catcalls–and delivered the satisfaction that comes from witnessing girls and women strike back. In this novel, young women collectively discover that their bodies are the source of electrical powers that they can wield. Suddenly, it is not so easy to silence and intimidate women. They can share their power with each other and with older women. Roxy, Allie, and Margot shock their way out of states of vulnerability and use their power to find safety and sisterhood. As I read about these women, I wanted a “skein” across my collarbone in which to store my own power. I wanted to create electric arcs between my palms. I wanted to run at night without fear.

I didn’t understand why Joss Whedon and Cory Doctorow would call this novel “scary and sad” and terrifying. I gobbled up the descriptions of women escaping from the literal chains of human trafficking and building their own nation. I wanted the orphaned Allie to lead the girls gathered at the convent, and I wanted Margot the small town politician to emerge as a wise and measured community leader. I even wanted Roxy, the child of a career criminal, to become a kinder, gentler mob boss. I rooted for these women.

And then. Well. The novel took a turn that surprised and horrified me–even though I should have seen it coming. After all, what does power do? It takes on the trappings of religious ceremony and government bureaucracy. Power seeks to reproduce itself. And, of course, power corrupts. It makes room for grotesque violence. The hunger for power–in this novel, at least–is not satisfied with safety and sisterhood.

This novel made me uneasy. It prompted me to wrestle with the nature of power and to re-imagine what the world would be like if power were redistributed. My husband would come into the living room to see who I was talking to because this book had me gasping and protesting aloud. The world Alderman creates (and destroys) in this novel is fully realized and all too familiar. The satisfaction I felt as I read those opening pages? Oh, it had a price.

Despite that, this novel was a gift, offering a smart and incisive meditation on, well, power.