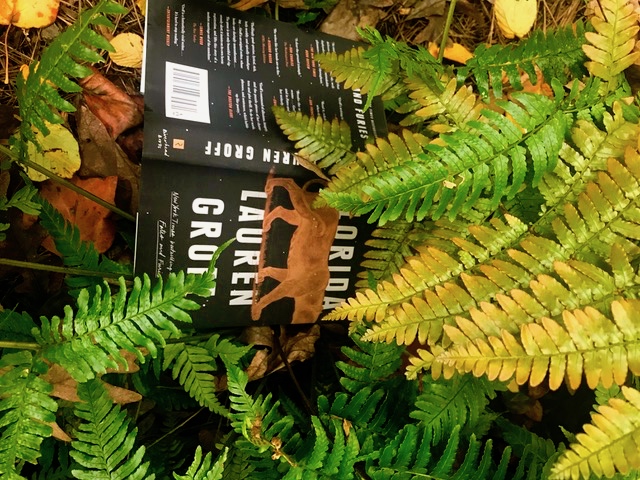

a bookclique pick by Laura Dickerman

Fetid, oppressive, and dangerous, the state of Florida, like a state of mind, like the United States, like a collective unconscious, lurks outside a barricaded door as a panther does in one of Lauren Groff’s powerful stories from her new collection, Florida. Groff’s 2015 novel, Fates and Furies, garnered her fame, though I was less taken with its allusive, mythological tale of a marriage from different points of view than I was with her earlier book Arcadia, a densely lyrical and layered exploration of a commune in upstate New York, from its Edenic conception to its complex unraveling. One of her many talents is sensuous, moody descriptions of place, whether it be the deep woods of the commune, the 1990s Bohemia of New York City, or the dank, destructive beauty of Florida, touched on in Fates and Furies, and developed fully into a multi-faceted presence in her latest book.

Florida is bookended with two stories narrated by the same character who makes appearances elsewhere, a woman who is a careful observer with a poet’s sensibilities, a conflicted mother to two young sons, and a literary soul whose sharp wit can hardly mask her despair. In the first story, “Ghosts and Empties,” she walks obsessively through her nighttime neighborhood, and in the last story, she flees on vacation with her sons and drinks copious amounts of wine to stave off realizations about her marriage, her profound loneliness, and the encroachment of dread that follows her from Florida to France.

In between there are stories that explore this omnipresent dread, stories about snakes, about alligators, dangerous men, abandoned children, killer storms. Groff touches lightly on political themes, but the effects of climate change or immigration policy or homelessness are woven into the deeper fabric of her work, so they never seem forced or heavy-handed. Her sentences are gorgeous, especially when she writes about the natural world in all its amoral glory and terror. There is a dream-like quality to many of the stories, nightmarish and strange, not exactly magical realism, but a murky depth peopled with ghosts, animal spirits, nature’s pitiless fury.

Even as the characters struggle to extract themselves from the swampy air of place, of company, of their own minds, these stories are never only heavy: the pervasive dread is pierced enough times to reveal flashes of beauty, of grace, of hope. The children in these stories are fully-realized, complicated people; there is solace in literature and the humanities that threads throughout; the language is lush and exacting, never overwrought but always precise; there is rueful humor and a final sense of humanity’s capability for kindness and nature’s capability for renewal. In the last image of the book, a little boy brandishes a stone above a snail, but his fist stays closed.

In one of my favorite stories, “Eyewall,” a woman who has barely survived a hurricane emerges from her battered home: “Houses contain us; who can say what we contain? Out where the steps had been, balanced beside the drop-off: one egg, whole and mute, holding all the light of dawn in its skin.”