a bookclique pick by Karen Derby

When I first read Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, I was fascinated with Tayo’s struggles as a Native American when he returns home from World War II. In Japan, he faced an enemy that looked strangely like himself. Silko’s novel made me question the concept of “American” identity. So when I read a review of Tommy Orange’s debut novel, There There, I knew I wanted to meet the “Urban Indian” that Orange wrote about. I was hopeful this novel would resonate with me as well as my students who face an increasingly complex understanding of American identity.

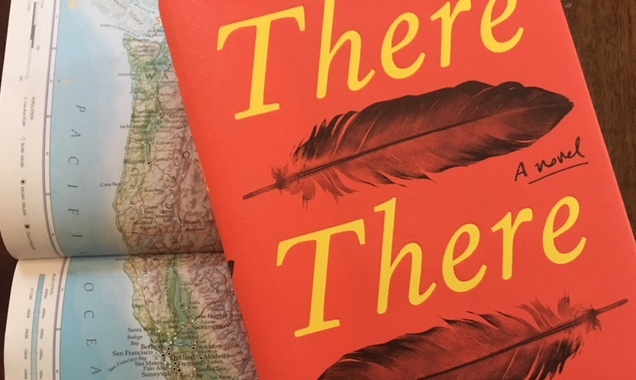

Orange takes his title from Gertrude Stein’s statement in her autobiography that “there is no there there,” upon returning to her childhood town of Oakland, California. Orange’s novel is set in 21st century Oakland, where Urban Indians attempt to survive. This Indian culture is decidedly different from other images of “Reservation” Indians we find in literature. In Oakland, Urban Indians blend with other groups – Mexicans, whites, poor, wealthy. Through twelve narrators, Orange develops one voice that tells the story of this Urban Indian, pulling them toward one pivotal event – The Big Oakland powwow.

Each of the twelve has varied reasons for attending the powwow, and many characters’ stories involve a search for the origins of their struggle as well as answers to why they want connection to something that feels so broken. There is Orville Red Feather, a young teen who teaches himself to dance at the powwow through YouTube videos; Edwin Black, who was an excellent student and a gifted writer, but who finds himself in his mom’s house, slowly gaining weight while spending hours on internet; Dene Oxendene, who inherits his uncle’s camera and uses grant money to film Indians telling their stories for a documentary-type of archive; and Octavio Gomez, who begins the novel as a drunk thug with aims of killing a friend’s brother, but whose later story offers some redemption.

Each of Orange’s characters is three-dimensional – with significant flaws, but capable of immense love. Through each character’s journey, Orange reveals so many aspects of this culture – music and story, connectivity and loss, spirituality and hopelessness. With irony, humor, and an interplay of narrative voices including 2nd person, Orange drives his readers toward a culmination of pageantry, hope, music, and dance, but also of fear, terror, and violence. And so the powwow becomes a metaphor for the history of Native American resilience, spirituality, ceremony, and oppression.

Like Silko, Tommy Orange challenges our conception of Indians, of what it means to be American, as well as the notion of Stein’s assessment of Oakland. In this first (and impressive) novel, I found much there here.