a bookclique pick by Jessica Flaxman

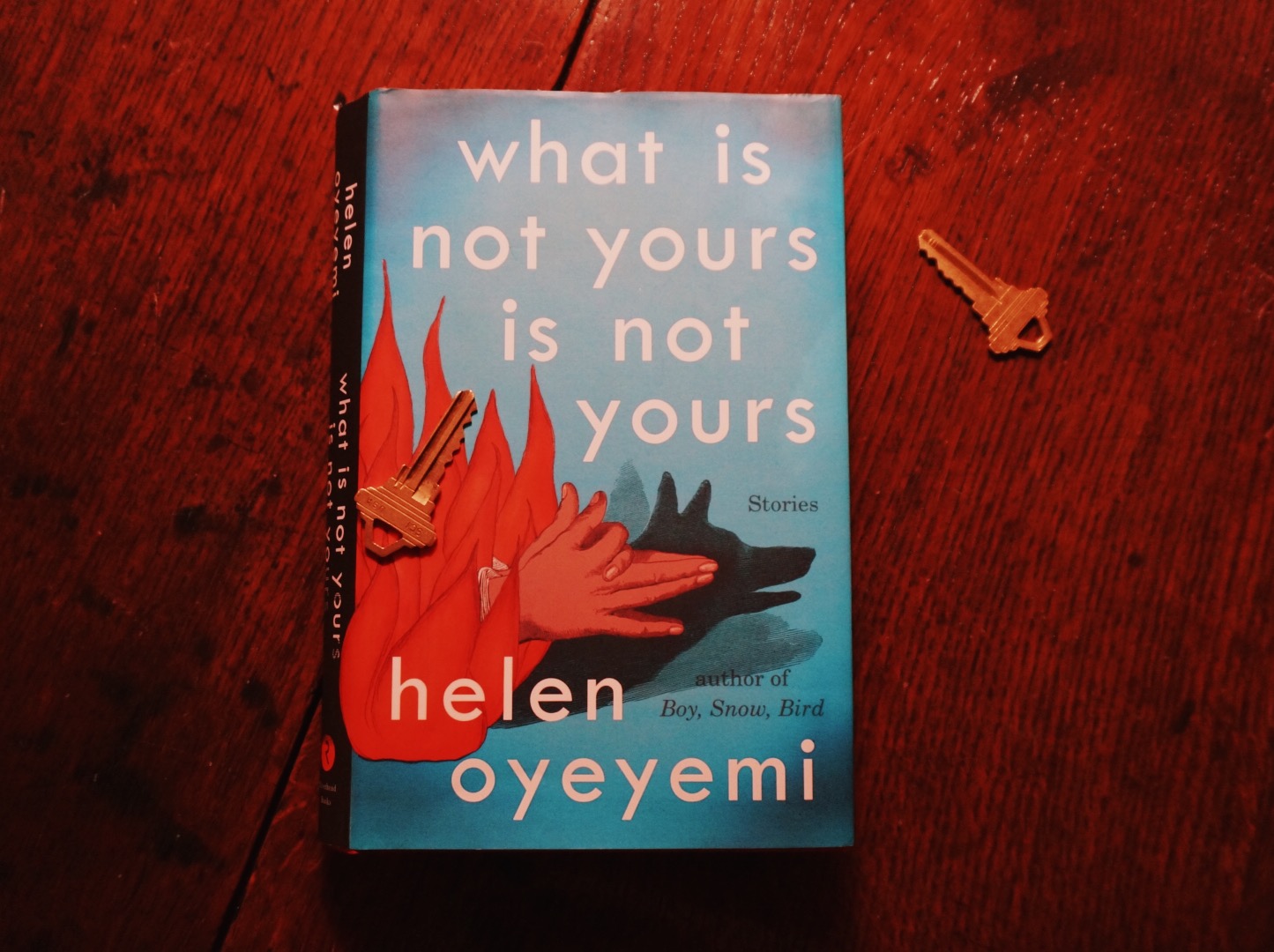

It’s true. What is not yours is not yours. No matter how much you want it, you can’t have it, if it isn’t yours. Helen Oyeyemi’s collection of short stories, What is Not Yours is Not Yours, explores the longing we all have for the things and people that are not ours despite our best (and worst) efforts.

Oyeyemi has made a name for herself since her first book, The Icarus Girl, was published while she was an undergraduate at Oxford. Her critically acclaimed fourth book, Boy, Snow, Bird, is one of the most interesting retellings of Snow White out there and is often taught in English classrooms where global perspectives are explored. Her latest book is even more compelling.

A master of her craft, Oyeyemi’s prose is lively, humorous, creative, and disciplined at every turn, mixing magical realism and the real world in a way that truly surprises the reader. When puppets and ghosts interact with human beings, we are more than willing to suspend disbelief. Hers is a kind of “Multicultural Uncanny,” as Porochista Khakpour wrote in a New York Times book review in 2014. The opening story in the collection, “Books and Roses,” introduces readers to Montse, who as a newborn was left at a church in Catalonia, Spain, with a gold key around her neck and instructions that read, “Wait for me.” An orphan raised by monks, Montse makes her way in the world by doing laundry at a large estate called La Perdrera, where she meets Lucy, “a painter with eyes like daybreak.” Lucy also wears a key around her neck. “I suppose we’re all waiting for someone,” she tells Montse before launching into her story of love, abandonment, and mysterious roses that kill.

In another story, “Sorry Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea,” a young girl finds it hard to forgive and forget when the celebrity she is in love with, Matyas Fust, commits an act of violence against a woman that is captured on video and shared online. Despite his apology, the child, Aisha, can’t let go and colludes with Tyche, a woman with presumably magical powers, to conjure the mythological Hecate. Hecate haunts Matyas, who begs forgiveness, to no avail. Only Aisha can release him, but at the story’s end, she is still weighing what to do. Oyeyemi writes, “She reckons Fust is getting closer to identifying his mistake, and says he should keep trying.”

Oyeyemi plants keys and locks into each of her carefully plotted stories, suggesting again and again that when things we think are beyond our grasp, all we need to do is look harder or in a different way. She’s comfortable with the idea, too, that key and lock may not always make their way to each other. It’s the journey and the search that she’s interested in, and more often than not, what is not ours remains just outside our reach. These fascinating interconnected short stories, however, become ours through reading.